The sprinklers cover the wide, softly undulating area with moisture. Cut so neatly, the grass looks artificial, and the little carts loaded with balls shine like the drawings in an animated cartoon. Everything is so perfect it hurts to look at it, so carefully prepared it looks unreal, dreamy, far away.

The new golf courses that are beginning to extend across Cuba appear profoundly strange to the national eye, aware as we are of the deterioration and improvisation that runs through the rest of the country. Their emergence has been preceded by infinite whispered discussions about the appropriateness, or not, of building these spaces for the luxurious entertainment of tourists in the middle of an economic crisis. Popular jokes, the criticisms of those who for years haven’t believed in the efficacy of government plans, and even the odd chorus of a reggaeton song, have nurtured the absurdity that these pockets of ostentation signify in our straitened circumstances.

The last word in this discussion has been the Sixth Congress of the Cuban Communist Party which approved the creation of these pompous entertainment venues for tourists. Number 260 in the Guidelines approved at this Party event confirms that priority will be given to the “development of these services: medical tourism, marinas and boating, golf and real estate, adventure and nature tourism, theme parks, cruises, history, culture and heritage, conventions, congresses and fairs, among others.”

The official justification has been the dire need of the national coffers to entertain visitors with their splendid pockets and well supplied wallets. “All-inclusive” travel packages have proved to be a highly profitable business for the Island’s authorities. Though a good part of the financial slice they provide goes to foreign tour operators, enough remains in the country to support the hotels.

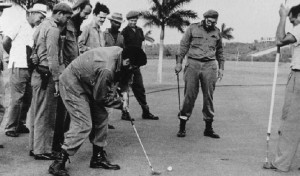

Thus, the new marketing strategy includes the promotion of other, more glamorous, recreational options that will attract the world’s tycoons, millionaires and aristocrats. A curious twist on the part of a government that confiscated and demonized private clubs which, before 1959, offered their members a little diversion with the club and a ball.

For decades the image of a gentleman in Bermuda shorts hitting a ball was the maligned stereotype of a past that would never return. In fact, many clubs to the west of the city, where wealthy Cuban landowners and businessmen engaged in the practice, were turned into military bases, schools, or recreational centers for workers and their families. “All this to now return it to the bourgeoisie,” say the most recalcitrant Cuban Communist Party militants.

And it’s true, they’re back. Although they are aesthetically beautiful, these green expanses provoke doubts in us rather than certainties. Our suspicion is not rooted in a rejection of this sport of eighteen holes, as if we cling only to baseball, the national pastime. Rather the uncertainty comes from knowing these recreation sites will be developed in a country marked by inefficient production, improvisation at every level, and the poor quality of most services.

If we add to this the lack of water which the current drought has worsened, then it is normal for the man on the street to anxiously wonder how they are going to maintain these impeccable lawns, other than at the cost of further reductions in the supply of this precious liquid for urban areas. The fear is, as happened with previous projects, that the whole economy is now focused on supporting the new idea of “luxury travel,” to the detriment of development projects perhaps less lofty, but more likely to come to fruition.

But the main complaint is knowing beforehand that all the investment in these areas is not aimed at us. That among the prerequisites to cross the thresholds of these leisure resorts is not just a check with numbers of more than five digits, but also the possession of a passport of any other country except our own. To know that they are there but they don’t belong to us, is one of the aspects that causes the greatest discomfort among a population that is not yet accustomed to being second class citizens in our own nation.

Without our presence, the golf courses will seem more unreal, or perhaps they will look exactly like similar facilities located in Thailand or Bermuda. They will, perhaps, be little spots of efficiency and comfort speckled across an Island submerged in the longest material collapse of its history. With perfectly cut grass watered by a constant sprinkled rain, these golf courses will enhance the contrast between tourist Cuba and the real Cuba, between those who hit the snow-white balls and those who can only watch from the other side of the fence.