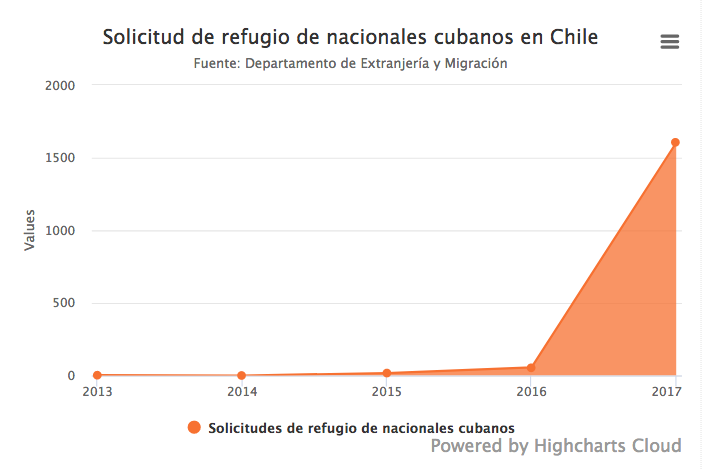

![]() 14ymedio, Mario J. Pentón, Miami, 16 February 2018 — The requests from Cubans seeking refuge in Chile have multiplied by a factor of thirty in a single year. According to the information provided to this newspaper by Chile’s Ministry of the Interior and Public Security, 1,603 Cubans requested that status at land borders in 2017. The previous year only 56 had done so.

14ymedio, Mario J. Pentón, Miami, 16 February 2018 — The requests from Cubans seeking refuge in Chile have multiplied by a factor of thirty in a single year. According to the information provided to this newspaper by Chile’s Ministry of the Interior and Public Security, 1,603 Cubans requested that status at land borders in 2017. The previous year only 56 had done so.

“Every day, migration officials collect between 15 and 30 passports to process refugee applications, and there are tremendous lines at the border,” says José Yans Pérez, a Cuban who was part of the group of rafters who occupied a lighthouse to the south of Florida in May of 2016, who were later returned to the Island. After traveling to Guyana, in a second attempt to escape from the country, he crossed the Amazon jungle and Bolivia to emigrate to Chile.

The route through these countries is “very complex and difficult,” explains Pérez, who after several months of work managed to get his wife out of Cuba for the same journey. Their two children remain on the island. “The biggest problem is that the documents take a long time. I arrived in Chile in September and I’m still waiting for my visa,” he says.

After the end of the United States’ wet foot/dry foot policy, announced in January 2017, thousands of Cubans who had planned to emigrate to the United States changed their destination towards the south. Countries such as Uruguay, Argentina, Chile and Brazil have registered a significant increase in Cubans reaching their borders.

Chile was already an attractive destination for Cubans before the end of the wet foot/dry foot policy. The Chilean government statistics show a 77% growth in the number of permanent residence permits granted to Cubans between 2014 and 2015. However, since the change in 2017 the movement has accelerated.

According to the Chilean law, people who can prove that they are persecuted for religion, race, political opinions or ethnicity may request refuge in that country. Rodolfo Noriega, Peruvian lawyer and leader of the National Coordinator of Immigrants (CNI), believes that Cubans, as a general rule, do not qualify under this rule.

“Many Cubans ask for refuge as a way to get around the migration entry controls along the land border,” Noriega explains via telephone from Santiago de Chile.

Once inside the country, refugee applicants undergo a series of interviews in order to formalize their request. The State offers them a visa for eight months that is extended until the authorities decide whether they will be recognized as refugees or not. With this visa they can work and live legally since the process takes years, according to Noriega.

“If to claim refugee status you assert that your country, in this case Cuba, is persecuting you, it is absurd for you to [voluntarily] return to Cuba,” says Noriega, who points out that many of the Cuban applicants may have problems with their applications for refugee status if they decide to visit the Island.

“Many Cuban professionals, after they have a job and become professionally licensed to practice in Chile, try to change their immigration status and find that if they withdraw their refugee application they immediately return to their earlier status, that is, undocumented,” explains the lawyer.

CNI is an organization that groups together more than 70 movements for the defense of the interests of migrants in Chile and that is currently pressuring the Government to award legal status to the more than 200,000 irregular immigrants now in the country. The movement, led by Noriega, has called for a march on Sunday to demand an extraordinary procedure for the regularization of all foreigners who are in the country.

“It is not how they paint it,” says Marelys Hernán, a Cuban who arrived in Chile after spending weeks stranded in Turbo, Colombia, failing to continue on to the United States.

“Cubans think that as the United States is closed, this is the second paradise, and they are arriving in packs and with a very bad attitude. They believe they have the right to receive help and to demand refuge, but that is not the case. Many Cubans end up on the street and in charity shelters because the Chilean government does not help,” she explains.

In her new life in Chile she has had to share the fate of thousands of Venezuelans and Haitians who see in this country a second chance to start their lives over. “This is hard, honestly, but we go in search of a dream and we will achieve it,” she says with hope.

______________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.