![]() 14ymedio, Luz Escobar/Mario Penton, Havana/Miami, 25 March 2017 – Maria, 59, has a daughter in Miami she hasn’t seen for six years. Her visa applications have been denied three times and she promised herself that she would never “step foot in” the US consulate in Havana again.

14ymedio, Luz Escobar/Mario Penton, Havana/Miami, 25 March 2017 – Maria, 59, has a daughter in Miami she hasn’t seen for six years. Her visa applications have been denied three times and she promised herself that she would never “step foot in” the US consulate in Havana again.

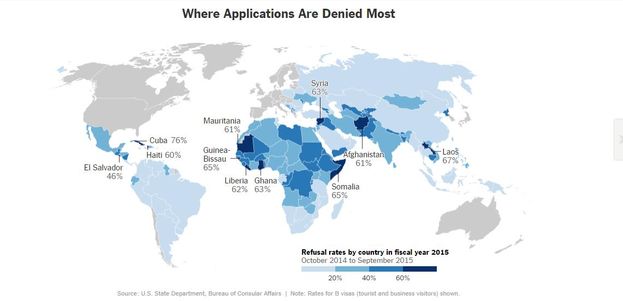

Cuba is the country with the most denials of those who aspired to travel to the United States in the last two years. In the midst of an abrupt drop in the granting of visas under Barack Obama’s administration, the Department of State rejected 76% of the travel requests made by Cuban citizens in fiscal 2015, according to figures released by the US press.

Cubans are followed on the US consulate most-rejected list by nationals of Laos (67%), Guinea-Bissau (65%) and Somalia (65%). In the Americas, the others most affected, although far behind Cubans, are Haitians (60%).

According to preliminary data released by the US State Department, the situation has worsened in fiscal year 2016, with Cuban visa applications rejected at a rate of 81.85%.

Each interview to request a visa cost Maria about 160 Cuban convertible pesos (CUC), with no chance of reimbursement, nor has she ever received any explanations about why her permission to travel was denied.

On each occasion the woman dressed in her best clothes, added an expensive perfume that her daughter sent her, and practiced her possible answers in front of the mirror. “No, I will not work during my stay,” she repeated several times. “I want to see my granddaughter who is a little girl,” and “I can’t live anywhere but Cuba,” she loudly repeats as a refrain.

She took with her the title to her house in Central Havana, a copy of her bank statement and several photos with her husband in case they asked her to provide reasons why she would not remain “across the pond.”

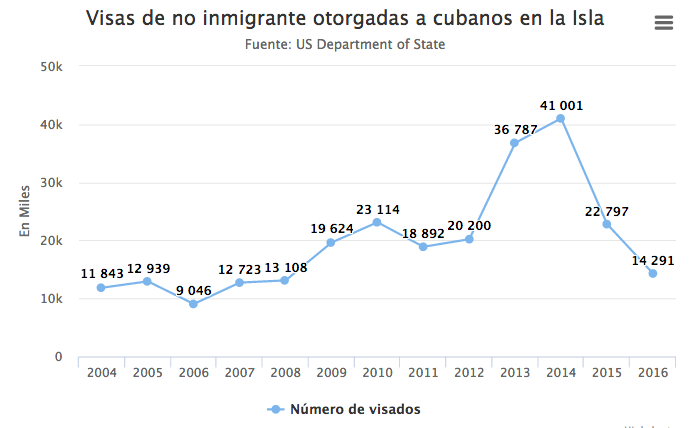

Last year 14,291 Cubans received visas for family visits, to participate in exchange programs, and for cultural, sports or business reasons, among other categories. The figure contrasts with the 22,797 visas granted in 2015 and, more strikingly, the 41,001 granted in 2014.

The State Department said that the reduction of visas granted in Havana is because of no specific reason, but that because the valid time period of the multi-entry visas was extended to five years in 2013, many islanders don’t need to return for new interviews to make multiple trips to the United States.

But Maria did not figure among the fortunate in any of her three attempts.

The last time she headed to the imposing building that houses that US consulate in the early morning hours, she prayed to the Virgin of Mercedes, made a cross with the sole of her shoe and put flowers before the portrait of her deceased mother.

She went to apply for a B2 Visa, the ones that allow multiple visits to the United States to visit relatives and for tourism. It seemed like the line lasted “an eternity” before they called her name, she said. Then came the iron-clad security to enter the building.

“The interview room had an intimidating coldness,” she recalls, and was long and rectangular. Applicants talked to immigration officials through shielded glass.

The woman’s feet trembled and the clerk on the other side of the glass gave her no time to explain much. He just made a mark on the form with each answer. A man was crying ata nearby window and an octogenarian lady sighed after hearing she was not approved.

More than two million Cubans reside in the United States, with an active participation in the economy and politics, primarily in South Florida

Maria knows that the United States and Cuba have signed an agreement for 20,000 Cubans to receive immigrant visas every year. In 1995, President Bill Clinton negotiated that agreement to end the Rafter Crisis, fueled by the economic recession that hit the island after the fall of the socialist camp.

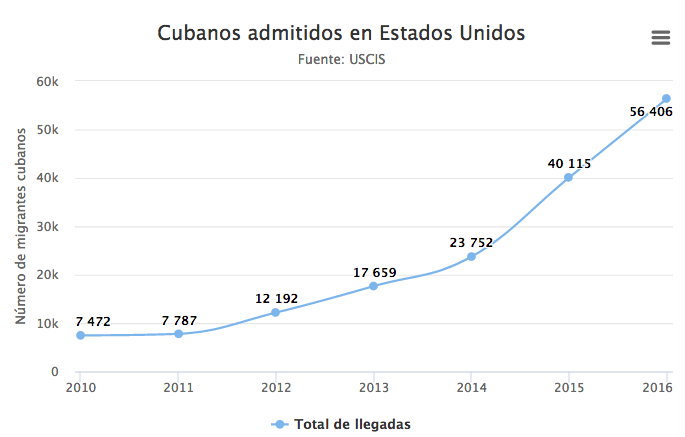

In 2016, 9,131 Cubans obtained a visa to legally emigrate to the United States, many of them under the Cuban Parole Family Reunification Program, and others through the International Lottery of Diversity Visas or the Cuban Parole program, among others.

More than two million Cubans reside in the United States, with an active participation in the economy and politics, primarily in South Florida.

The Cuban Adjustment Act, approved in 1966, allows Cubans to obtain permanent residence (a green card) if, after entering legally, they spend one year in the United States. A special welcoming policy only for Cubans known as wet foot/dry foot was cancelled in January; this policy allowed any Cuban who stepped foot in the country, even without papers, to remain, while Cubans who were intercepted at sea were returned to the island. In the last five years 150,000 Cubans took advantage of this policy to settle in the United States.

However, Mary’s intention is not to emigrate. She does not want to live in a country that is not her country, although her relatives have told her that Miami “is full of Cubans” and that Hialeah is like Central Havana.

Despite her Afro-Cuban rites and trying to maintain a positive mental attitude, in her last interview she didn’t have any “luck” either.

She received a quick denial and was given no chance to display all the answers she had rehearsed. In her opinion, the fact of being under 65 plays against her. “They approve older people who cannot work illegally there,” the lady assumes.

For Eloisa, a retired science teacher, that is not the reason, rather it is “hostility toward Cubans” by the US Government.

“The Americans want to take over Cuba. It has always been their greatest desire and because they cannot do it, they punish us by separating us from our children,” the woman says by phone. She has been a member of the Cuban Communist Party for 25 years and has had two children living in Houston for just over six years.

Although she only tried once, last year, the refusal from the consulate made her not want to try again.

“My children work very hard and I wanted to give them the pleasure of going to spend a little time with them. But hey, it’s not to be, “ she says in a voice that is brittle and resigned.

Mary, however, does not tire. This year her daughter will gain American citizenship and the woman hopes that this new condition will facilitate a positive response to her next request. Although this new attempt will leave her a little older and with almost $500 less in her pocket, in a country where the average monthly salary does not exceed $28.