Iván García, 16 March 2106 — Around 12 midnight on Tuesday, 18 March 2003, I was en route to my apartment in the La Víbora neighborhood when, from the balcony, some incomprehensible signs coming from my mother set off the alarms.

Those were hard years. My mother and I were contributing articles to the independent press agency, Cuba Press, prohibited by the government, which was led by the poet and journalist Raúl Rivero. We were detained, intimidated or warned by cowboys from State Security with too much insistence.

Fidel Castro, meticulously, had prepared his “crime” scene. Since February 1996, when MiG aircraft shot down four civilian aircraft of the Brothers to the Rescue, and with the turn of the screw to the embargo on the part of Bill Clinton’s administration, the olive-green strongman unleashed his furies upon the peaceful opposition.

In 1999, the obedient and one-note national parliament had approved Law 88, a legal platform that allowed the government to impose prison terms of up to 30 years on dissidents, human rights activists, and independent journalists.

The acts of repudiation conducted on our domiciles were frequent. We lived in a climate of fear. But we continued reporting stories about the other Cuba, the one that was never reflected in the official press.

That night, my mother tells me that she had gone to turn in some articles to Raúl Rivero at his home in Centro Habana and, no sooner had she arrived but Raúl tells her that State Security had been searching the homes of Ricardo González Alfonso and Jorge Olivera, and that as soon as these searches were over, they would be taken into custody. “He said that I should return immediately and tell you,” she recounted, “because at any moment, they would come looking for the two of us.”

Two days later, on Thursday 20 March, Blanca–Raúl’s wife–tells us that at around 5 pm, he had been arrested. “The operation was tremendous,” she said. “Television cameras, several patrol cars and dozens of police officers, as if he were a terrorist. But when the neighbors found out, they went out into the street and several of them screamed.”

Throughout the following hours and days, we learned of other arrests of colleagues in the capital and the provinces. Their weapons: typewriters. Their crime: to dream of democracy in Cuba.

I was going around with a toothbrush and a spoon in my backpack. The atmosphere was oppressive. Hijackings of commercial airlines and ships were taking place. In a summary trial, Fidel Castro ordered the execution of three young black men who had hijacked an old passenger ferry. It was a state-sponsored execution.

The regime’s reasoning, taking advantage of the start of the war in Iraq, was that the raid would be unnoticed. It was not so. Presidents, intellectuals and international media focused on the wave of repression. In its prosecutions, the government was requesting the death penalty for seven opposition members.

Years later, Raúl Castro, handpicked as president by Fidel–pressured by the fatal hunger strike of the dissident Orlando Zapata Tamayo, and by the marches of the Ladies in White demanding the release of their husbands, fathers and sons–initiated negotiations to free the government opponents, as part of a troika with the Catholic Church and the Spanish chancellor Miguel Ángel Moratinos.

The military autocracy undertook lukewarm economic reforms that were indispensable to its continuance in power. The furniture was moved around, but the same décor was maintained.

It was not a gamble on market economics or democracy. No. It was a play for survival. They legalized absurd, feudal-style rules that had kept Cubans from accessing mobile telephones, hotel lodging, buying cars or selling their homes. But structurally, the essence of the regime was–and still is–maintained.

Thirteen years later, in Spring of 2016, you can say whatever you want. But you cannot create a political party, an independent association, or a print newspaper.

In the economic sector, the opening is limited. There is no coherent legal framework for private entrepreneurs who, lacking a wholesale market where they can buy their raw materials and ingredients, must resort to trickery, corruption and cooking the books.

The State continues to classify self-employed workers as presumed delinquents. The regime’s economic guidelines–its holy bible–warns that the government will not consent to the concentration of capital in private hands. The new investments law does not permit investing in the self-employed.

What have been the changes undertaken by the Cuban autocracy? The prime transformations have been in foreign policy. Key aspects of Cuban diplomacy have undergone a 180-degree turn during Raúl Castro’s term in office.

The Havana regime has gone from training guerrilla groups or terrorists in their territory, to negotiating a place in world financial mechanisms, to signing new treaties with the United States and the European Union, to mediating between the Catholic and Orthodox churches, to being an important actor in achieving a peace accord in Colombia.

Cuba has opened itself to the world, as Pope John Paul II asked, but not to Cubans. At the internal level, the aged gerontocracy’s resistance continues, with its anachronistic concepts of social control, absence of political liberties, and suppression of free expression. In the economic area, the reforms are limited and insufficient.

When Raúl Castro regards his reflection in the mirror, he does not see himself as Wojcieh Jaruzelski, the Polish leader who opened the fortress to democracy. He would like to be remembered as the man who perpetuated his brother Fidel’s “Revolutionary work.”

It is necessary to prognosticate what Cuba’s future might be. To open a Pandora’s box in closed societies is always a dangerous game. And a presumed redeemer can turn into a probable gravedigger.

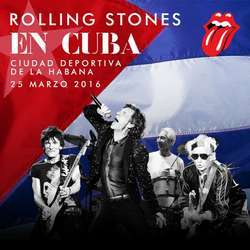

Perceptions are deceiving. A great red carpet for President Obama, a mega-concert by the Rolling Stones, a recent accord with the EU, and the imminent signing of a commitment between the FARC and the Colombian government to put an end to the continent’s last armed conflict.

But on the Island, repression of frontline dissidents and arbitrary arrests continue–as do low wages, high cost of living and a questionable future. This is why many Cubans are opting to emigrate.

Translated by Alicia Barraqué Ellison