![]() 14ymedio, Pedro Campos, Havana, 29 December 2015 — Cuba is the only country in this hemisphere that does not conduct democratic multi-party elections, which is what the Revolution of 1959 fought for and what different wings of the democratic left and the opposition forces of all stripes have been advocating for years.

14ymedio, Pedro Campos, Havana, 29 December 2015 — Cuba is the only country in this hemisphere that does not conduct democratic multi-party elections, which is what the Revolution of 1959 fought for and what different wings of the democratic left and the opposition forces of all stripes have been advocating for years.

Democratization of the political-economic process is an urgent need for Cuban society. A historical debt to the people. The 1959 Revolution attracted the support of everyone because it is proposed to restore the democratic 1940 Constitution and the institutional system interrupted by the 1953 coup. This has been postponed indefinitely.

It is no secret that the economic and politically centralized state model imposed on Cuba in the name of socialism has failed all along the line. Its inability to fulfill its own agreements from the Sixth Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba is conclusive. The model isn’t even capable of implementing the modifications approved by its own party and leaders.

President Raul Castro says he will retire from the leadership of the government in 2018. With him, the fundamental base that has sustained the regime in power for more than half a century will also go: the glories of the attack on the Moncada Barracks, the yacht Granma bringing the revolutionaries back from Mexico, and the fight in the Sierra Maestra. And no matter how much those who come after want it, they will no longer have those credentials. And they cannot, not even if they carry its name, for the simple and sensible reason that they were not there, the test of authenticity imposed by the Castro brothers themselves. The Revolution was their source of power, but legitimacy is another thing altogether.

If, before finally retiring from the government, Raul Castro is not subject to a direct and secret popular vote, future generations will always be left with the doubt about whether the work of the Castro brothers was done with or without the support of the majority of the people.

If he were elected president, he could still retire and fulfill his promise to leave power, but leaving a vice president no longer tied to those glories but with legitimacy won at the ballot box. And if he doesn’t want to or can’t face elections, let the Cuban Communist Party candidate he supports and for whom he would openly campaign be submitted to a popular vote. The success or failure of their candidate would be that of the Castros.

But if their candidate is not submitted to such scrutiny, not only would the doubt about the true popular support for the Castros continue, but the legitimacy of the successor would always be in question, because he or she would not even have these glories, nor would they have been elected by popular vote.

As the leaders and the current high level bureaucracy of the Communist Party is convinced that they can always count on the support of the majority of Cubans, there should be no reason in the next elections not to elect the president and vice president of the republic by popular vote, along with the provincial governors and city mayors.

This would bring enormous benefits for the current government. In fact, if they were to initiate and develop in 2016 a process of democratization that implies a fundamental respect for Cubans’ human rights, such as freedom of expression, election and economic activity, and that establishes a new constitution and a new electoral law that enables truly democratic elections, what remains of the US blockade-embargo would be completely undermined, forcing its immediate repeal by the United States Congress.

This would be, in fact, a triumph of their government and would help them in democratic elections and could also contribute, depending on who wins the upcoming elections in the United States, to an expedited normalization of relations with that country.

Moreover, within a couple of years economic and political liberalization would generate rapid economic growth, slow the exodus of Cubans overseas, and make all Cubans feel free to express themselves, organize parties and associations, promote their political proposals, vote for whomever gives them real economic gains thrugh deploying their abilities of every kind, which would be visible at the time of the elections and could widely favor popular support for the government candidate, if he or she was in the vanguard of this democratization.

“You’re dreaming, Pedro Campos,” more than a few readers will comment. No, my friends, this is no dream. Nor are they hopes, though woe to anybody who does not have them! I am trying to bring some light to the path for the good of everyone. Whether they see it or not, that’s another thing. Some think that if there is openness, the opposition will erase the government. Not if the opening is truly democratic and authentic.

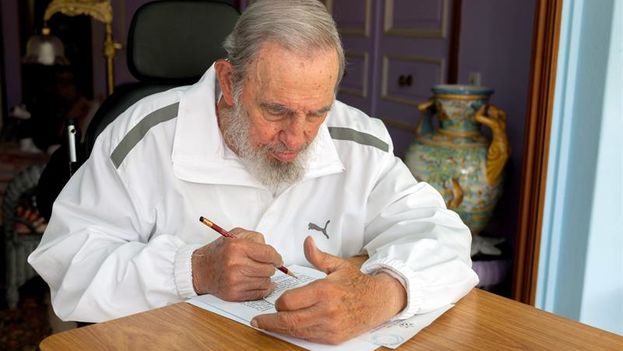

It is very clear that those who spearhead the process of democratization, now or later, are going to lead the country in the following years. The opposition did not bury Mikhail Gorbachev, it was the military conservatives. Here, I do not think any members of the military could do something similar. And the other thing that is clear to all Cubans is that this model of state capitalism disguised as socialism has no future. “This model doesn’t even work for us any more,” Fidel Castro himself said once, although later he “clarified” that he had been misinterpreted.

I imagine that no one will go down in history as the gravedigger of the Revolution, above all if it is the Revolution itself that makes possible the opening to full democratization and development of the country.