![]() 14ymedio, Mario Penton and Luz Escobar, Miami and Havana, 14 July 2017 — Ileana Sánchez is anxiously rummaging through her tattered wallet, looking for some bills to buy a toy slate for her seven-year-old granddaughter who dreams of becoming a teacher. She has had to save for months to get the 20 CUC (Cuban convertible pesos, roughly $20 US) that the gift costs, since her monthly salary as a state inspector is only 315 CUP (Cuban pesos), about 12 dollars.

14ymedio, Mario Penton and Luz Escobar, Miami and Havana, 14 July 2017 — Ileana Sánchez is anxiously rummaging through her tattered wallet, looking for some bills to buy a toy slate for her seven-year-old granddaughter who dreams of becoming a teacher. She has had to save for months to get the 20 CUC (Cuban convertible pesos, roughly $20 US) that the gift costs, since her monthly salary as a state inspector is only 315 CUP (Cuban pesos), about 12 dollars.

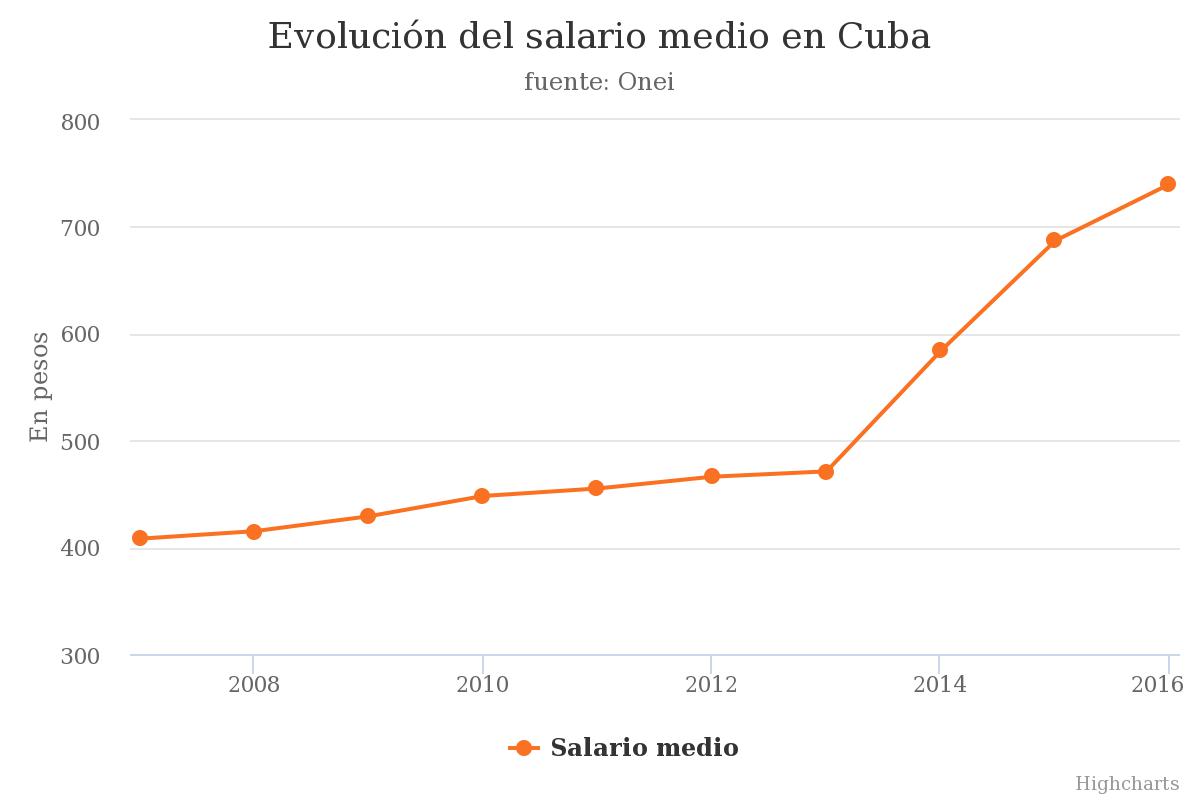

At the end of June, the National Bureau of Statistics and Information (ONEI) reported that the average salary at national level reached 740 CUP per month, slightly more than 29 CUC. However, the increase in the average salary does not represent a real improvement in the living conditions of the worker, who continues to be able to access many goods and services only through remittances sent from family abroad, savings and withdrawals.

“I do not know who makes that much money, nor what they base these figures on, because not even with the wages my husband earns working in food service for 240 CUP a month, along with my wages, do we get that much,” says Sanchez.

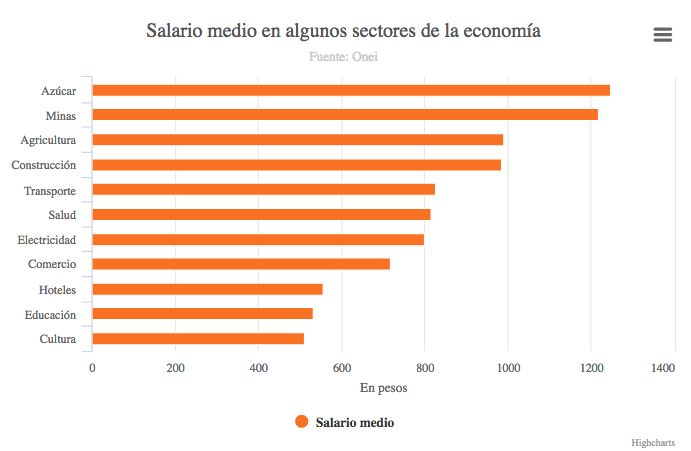

The ONEI explains that the average monthly salary is “the average amount of direct wages earned by a worker in a month.” The calculation excludes earning in CUC. However, the average salary is inflated by the increases in “strategic” sectors, such as has happened in healthcare, where the pay has been more than doubled, while in other areas of the economy wages have remained practically unchanged for over a decade.

“If you buy food you can not buy clothes, if you buy clothes you can not eat, we live every day thinking about how to come up with ways survive,” she says in anguish.

Most Cubans do not support themselves on what they earn in jobs working for the state, which employs 80% of the country’s workforce.

President Raúl Castro himself acknowledged that wages “do not satisfy all the needs of the worker and his family” and, in one of his most critical speeches about the national reality in 2013, he said that “a part of society” had become accustomed to stealing from the state.

Sanchez, on the other hand, justifies the thefts and believes that the “those who live better” are those who have access to dollars or those who receive remittances. “Anyone who doesn’t have a family member abroad or is a leader, is out of luck,” she says.

According to the economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago, when speaking of an increase in the average wage, a distinction must be made between the nominal wage, that is, the amount of money people receive, and the real wage, adjusted for inflation.

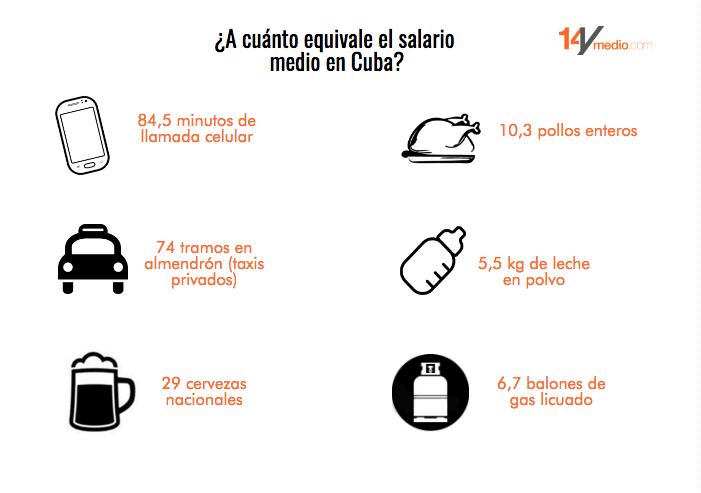

A recent study published by the academic shows that although the nominal wage has grown steadily in recent years, the real wage of a Cuban is 63% lower than it was in 1989, when Cuba was subsidized by the Soviet Union and the government had various social protection programs. At present, the entire month’s salary of a worker is only enough to buy 10.3 whole chickens or 7.6 tanks of liquefied gas.

Among retirees and pensioners, the situation is worse. The elderly can barely buy 16% of what a pension benefit would buy before the most difficult years of the so-called Special Period – the years of economic crisis after the fall of the Soviet Union – according to Mesa-Lago.

Or by another measure, spending an entire month’s salary a worker can only afford 19 hours of internet connection in the Wi-Fi zones enabled by the state telecommunications monopoly, Etecsa, or 84.5 minutes of local calls through cell phones.

To buy a two-room apartment in a building built in 1936 in the central and coveted Havana neighborhood of Vedado a worker would need to save their entire salary for 98 years, while a Soviet-made Lada car from the time of Brezhnev would cost the equivalent of 52 years of work.

However, the island’s real estate market has grown in recent years at the hands of private sector workers who accumulate hard currency, or by investments made by the Cuban diaspora. In remittances alone, more than three billion dollars arrives in Cuba every year.

According to Ileana Sánchez, before this panorama many people look for work in the areas related to state food services or administration where they can steal from the state, or jobs that provide contact with international tourists such as in the hotels.

Other coveted jobs in the private sphere are the paladares – private restaurants – and renting rooms and homes to tourists where you can get tips. The “search” (as the theft is called) has become a more powerful incentive to accept a job than the salary itself.

Although, according to the document published by the ONEI, workers in the tourism and defense sector earn 556 and 510 pesos on average, many of them receive as a bonus a certain amount of CUC monthly that is not reflected in the statistics, and they also have access to more expensive food and electrical appliances than does the rest of the population.

Among the best paid jobs in CUP, in order of income, are those in the sugar industry, with 1,246 CUP on a monthly basis, and in agriculture with 1,218. Among the worst paid jobs according to the ONEI are those working in education, with 533 CUP, and in culture with 511.

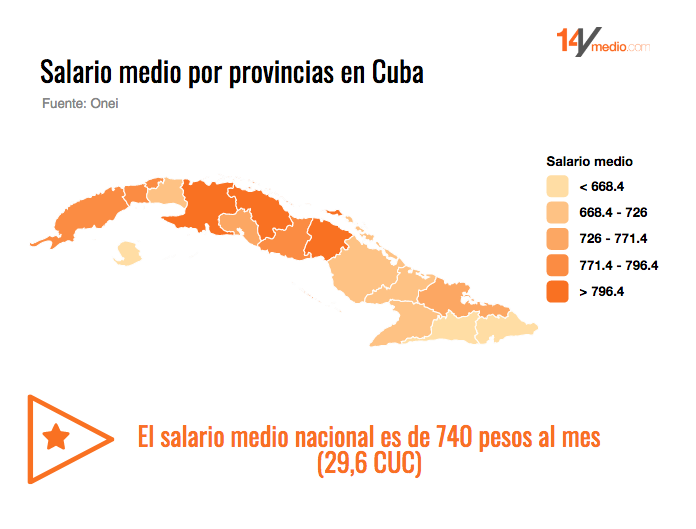

For Miguel Roque, 48, a native of Guantánamo, low wages in the eastern part of the country are driving migration to other provinces. He has lived for 12 years in the Nuclear City, just a few kilometers from Juraguá, in the province of Cienfuegos, where the Soviet Union began to build a nuclear plant that was never finished.

“The East is another world. If you work here, imagine yourself there. A place stopped in time,” he explains. Roque works as a bricklayer in Cienfuegos although he aspires to emigrate to Havana in the coming months, where “work abounds and more things can be achieved.”

The provinces where average wages are highest, according to the ONEI, are Ciego de Avila (816 CUP), Villa Clara (808 CUP) and Matanzas (806 CUP), while the lowest paid are Guantanamo (633 CUP) and Isla de la Juventud (655 CUP).

“Salary increases in the east of the country are not enough to fill the gaps with the eastern and central provinces,” explains Cuban sociologist Elaine Acosta, who believes that cuts in the social services budgets are aggravating the inequalities that result from the wage differences.

“It is no coincidence that the eastern provinces have the lowest figures on the Human Development Index,” he asserts.