![]() 14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar (Special envoy), Liberia (Costa Rica), 28 November 2015 — A uniformed policeman guards the entrance to the shelter in the church of Nazareth, in the Costa Rican region of Liberia. It is there to protect 70 Cubans who are waiting for the Nicaraguan authorities to allow them to continue their journey to the United States. Journalists are not allowed access, not least because most migrants prefer not to give interviews.

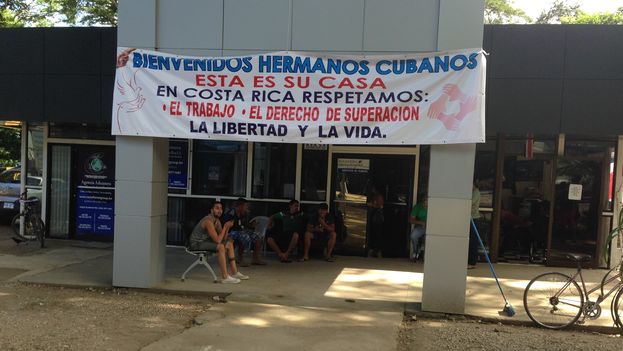

14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar (Special envoy), Liberia (Costa Rica), 28 November 2015 — A uniformed policeman guards the entrance to the shelter in the church of Nazareth, in the Costa Rican region of Liberia. It is there to protect 70 Cubans who are waiting for the Nicaraguan authorities to allow them to continue their journey to the United States. Journalists are not allowed access, not least because most migrants prefer not to give interviews.

However, the Cuban accent opens all doors. Once inside, a young man from Pinar del Rio explains that his family does not know he is in that situation and he does not want to worry his mother. “She believed I was going around the stores in Quito to buy clothes and then sell them back home in San Juan y Martinez.” Something similar occurs with Maria, an enthusiastic and charismatic woman from Camagüey, who spurred by the emergency has become the voice of the group.

Maria is a little frightened to comment: “I don’t want, tomorrow, for the Cuban government not to allow me to visit my family.”

Maria is the representative of Cubans who are there. Nobody gave her that position, no one voted for her, but her way of expressing herself and showing natural leadership have led her to speak for those who prefer to remain silent. However she confessed to this newspaper that she finds it a little frightening to make statements: “I don’t want, tomorrow, for the Cuban government not to allow me to visit my family.”

The hostel recalls the Cuban schools in the countryside through which passed the Maria’s and the young Pinareño’s generation. The difference here is that they are not forced to work in agriculture, nor to listen to the tiresome ideological propaganda of the morning assemblies. They are free, but have one obsession: continuing the path to the “land of freedom,” they say.

Sioveris Carpio left on 3 September for Ecuador. He never imagined that his journey would be complicated in this way. He arrived in Costa Rica on 12 November when the border with Nicaragua was already closed. Now, when asked if he wasn’t tempted to turn around, he uses a slogan heard thousands of times from Cuban officialdom: “Pa’ tras ni para coger impulso*.” And he adds with a smile, “My objective is to get there.”

He is an amateur musician, finished the 12th grade, and had worked as an animator and audio operator in Trinidad, but he lives in Condado, a corner of Escambray where the alzados – the anti-communists – were active in the sixties. “I live near where there is a monument to Manuel Ascunce, the literacy teacher killed by the alzados,” he says, and immediately clarifies, “the fact that I am going to the United States doesn’t mean that I’m against the Revolution.” In the conversation there is only this reporter and the impassioned young man, but at times he speaks as if a thousand ears are listening.”

“I was born and raised under a Revolutionary roof, what is happening is that I am looking for an economic improvement,” says Carpio Sioveris

“I was born and raised under a Revolutionary roof, what is happening is that I am looking for an economic improvement,” he says. He repeats the litany of many about his decision, that he “isnot political”, but admits that he has chosen the United States” because it is a country where you can find an opportunity to prosper.”

If “things get bad” and he can not continue toward reaching his dream, he will stay in Costa Rica. “Right here,” he says and states that “people are good and we have the same language, but life is expensive and it is not easy to find work.”

In Cuba he left his entire family and says that his parents “are suffering a lot because they know I’m here.” His dream, however includes the goal of one day returning to Cuba. “Not now, because unfortunately there are no opportunities, wages are minimal to the point that if you buy a pair of pants you can not eat that month.”

Carpio is a skeptic of the economic changes that have occurred on the island in recent years. “The results will be seen only long term. We will have to wait a long time and I am almost 40.” The clock of his life has marked a critical time and he prefers to spend the rest of it in foreign lands.

“Here on the roof of my house I have an antenna for television and they tell me that in their country satellite dishes are prohibited,” says a Costa Rican

But Carpio is only part of this drama. The people of Nazareht have seen dozens of these migrants arriving on their territory and have come out to help them. Mauricio Martinez has lived, from birth, across from the Bethel church in the Nazareht neighborhood, although he is not a member of the church. Now he dedicates many hours of his time talking to the Cubans.

“I’ve never seen anything like what’s happening here today. At first we had some concern, but the people are very quiet and very well educated. They are very friendly,” he confirms.

The help that the community has given to migrants has been spontaneous. People bring clothes or food, “according to what everyone can because we are humble people,” says Martinez. “But we’ve realized what is thay are going through and so we are collaborating,” he reflects.

The arrival of the Cubans is also leaving a deep impression in the way many Costa Ricans see the world. “Knowing them has allowed us to learn a very different reality to ours and also different from what we could imagine,” says a solicitous neighbor. “Here on the roof of my house I have an antenna for television and they tell me that in their country satellite dishes are prohibited, and thus I realize what they are looking for in freedom” he says.

A vehicle from the firm Movistar is parked front of the shelter. Mr. Benavides, a sales agent, is satisfied with his success in selling phones, SIM cards and recharges to the Cubans. “Since we learned that the shelters were filled with these migrants we assumed that they probably wanted to communicate with their families.”

“I came here with my wife but I left my four children, two grandchildren and my mother,” says Julio Cesar, who operated a tire retreading machine

The employee says that “there is a commercial interest, but the first thing that got us here was the desire to help.” He adds, “It’s amazing how they know the brand names, they are modern people and are eager to prosper.”

It is not easy to win the confidence of those who have had to sneal across several borders and fear that what little money they have left will be taken away or that they will be deceived by traffickers, but some speak to this newspaper with the familiarity of old friends.

Julio Cesar Vega Ramirez of San José de las Lajas, is not afraid of anything. He left Ecuador heading to Colombia without knowing the way, then by boat to Panama and then to Costa Rica, where he was given a pass for seven days that has been extended for fifteen more. “With this visa we can move around the country freely,” he says.

The man says that “everyone here has helped us, the church’s neighbors, the organizations. They bring sacks of cassava or bananas without charging a cent. The Cubans living in San Jose have also brought donations. ” Although he has also had the support of his family in Miami. “They have sent me the money bit by bit because it is not advisable to walk around with a lot of money,” he explains.

Julio César operated a tire retreading machine. “I came here with my wife but I left my four children, two grandchildren and my mother.” He said his family was aware of what was going to do. “Although I said nothing at work for fear that someone would spill the beans and spoil the plan.”

His wife, Maritza Guerra, has a degree in nursing and a master’s degree in comprehensive care for children. For years she has been a nurse in the pediatric ward of the Leopoldito Martinez Hospital in San José de las Lajas. It is also pediatric intensive care nurse. “Here we communicate with our families and friends thanks to wifi zone they immediately established for us completely free. I would like to ask those Cubans in exile and on the island to help us, please, do something for us,” she clamors insistently.

In the afternoon, when the sun goes down, the trees are filled with birds. The noise they make is very different from the sparrows in the parks of Cuba, because there is a lot of variety and they all sing differently. Birds coexist with each other and fly freely from one side of the border to the other.

*Translator’s note: Para atrás, ni para coger impulso. Roughly: No going back, not even to gain momentum (for another charge).