![]() 14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, 9 December 2018 — We have Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) to thanks for the novel Fahrenheit 451 (published in 1953) that tells the story of Guy Montag, a fireman whose job is to burn books considered ‘uncomfortable’ by the government. Such an atrocity was only possible because there was a powerful commission in charge of dictating what was right and what was not.

14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, 9 December 2018 — We have Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) to thanks for the novel Fahrenheit 451 (published in 1953) that tells the story of Guy Montag, a fireman whose job is to burn books considered ‘uncomfortable’ by the government. Such an atrocity was only possible because there was a powerful commission in charge of dictating what was right and what was not.

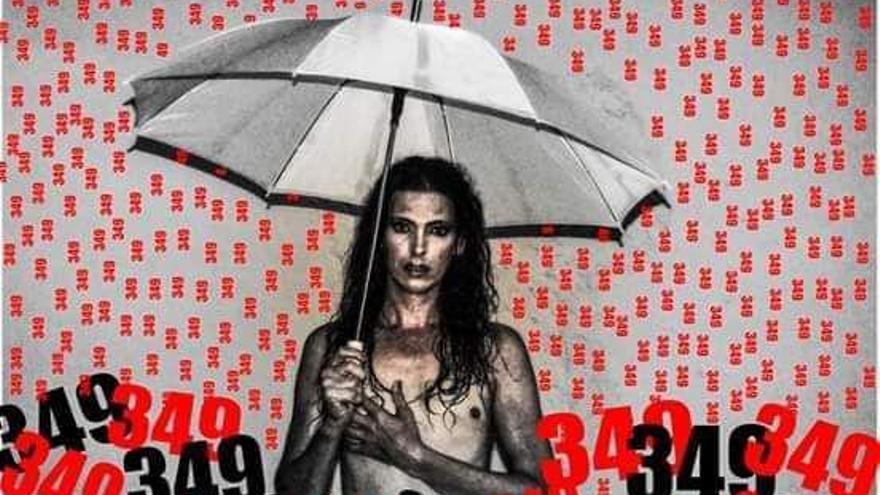

One of the main disputes that has prompted the enactment of Decree 349 in Cuba is precisely the creation of a “fire department” which, under the definition of an “authorized authority” or “inspector,” has the power to “immediately suspend the performance or projection in question” as expressed in Article 5.2 of this regulation.

On the Roundtable program aired on Cuban television last Friday, the members of a team made up of Alpidio Alonso, minister of culture, deputy minister Fernando Rojas; Lesbia Vent-Dumois, president of the Association of Plastic Artists of the Cuban Writers and Artists Union, and Rafael González Muñoz, president of the Hermanos Saíz Association, made an effort to show that those who did not accept the Decree were confused, had doubts or had not read it well. At no time did they use the verb “to disagree.”

The Roundtable once again maintained its traditional method of not inviting to the “debate” to those who think differently from the government. Divergent opinions were maliciously ridiculed by the panelists with the hackneyed device of reducing the arguments of the absent opponents to an absurdity.

For example, Fernando Rojas denied that artists had to ask for permission to exhibit their work although among the violations described in the decree is mentioned “he who as an individual artist or acting on behalf of the group to which he belongs, provides artistic services without the authorization of the appropriate [government] entity.”

Rojas also stated that it was false to say that the text of the regulation established the obligation to be a member of an institution and added that “in no passage of the Decree is that said, and I have the impression that this has to do with a subsequent manipulation to allege that the decree is addressed to the amateur.”

Here Rojas ignored that although the Decree does not explicitly state the obligation of the artist to be linked to an institution, it sanctions “someone who provides artistic services without being authorized to perform artistic work in a position or artistic occupation.”

The alleged suspicion that the Decree is directed against the amateur artist does not belong to the group of concerns expressed by its critics who have expressed concern about how it will affect independent artists who, while professionals, do not “belong” to any state institution.

In relation to the conduct of the inspectors, Fernando Rojas warned that “this action will always be preceded by a collective reflection of an analysis of the institutions with the participation of the creators, it will not be something imposed or improvised,” a statement which denies the power explicitly granted to these inspectors to “immediately” suspend a show or presentation.

It was repeated to the point of exhaustion that the Decree was not directed against the creators or against the act of creation, but rather it regulated the distribution and commercialization of art in public spaces. This argument recalls the statement of the then all-powerful Carlos Lage in Geneva in May 2002, where he said that Cubans had “total freedom of thought,” but without mentioning the limitations of freedom of expression.

In a country where almost all of the publishing houses, galleries, theaters and cinemas are in the hands of the State, it is a joke in bad taste to confirm the “freedom of artistic creation” while reinforcing the locks that limit the diffusion of what is created.

Censorship is masked by good intentions. It is presented as essentially a crusade against bullying, bad taste, vulgarity and manifestations that encourage violence or that incite discrimination based on gender, race, disability or sexual preferences.

But in “the fine print” where it lists the contents that should not be disseminated by the audiovisual media, it includes the statement “any other that violates the legal provisions that regulate the normal development of our society in cultural matters,” and among the behaviors which a legal or natural person should not incur, it includes the commercialization of books “with contents that are harmful to ethical and cultural values.”

Minister Alonso was decisive when he said that “the enemies of the Revolution have wanted to present the Decree as an instrument for censorship,” but neither he nor any of the Roundtable panelists had the essential transparency, honesty or courage to mention the names of Tania Bruguera, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Yanelys Núñez, Michel Matos and Amaury Pacheco, who led the protests.

If the method of reducing to absurdity the arguments of the other side were used against the defenders of Decree 349, it could be said that it is fortunate that it has not been implemented in the past, because if so, a good part of our cultural production would have to be revised inquisitorially.

Painter Carlos Enríquez’s The Abduction of the Mulatto Women would not be exhibited in the museum due to its sexist, racist and gender violence-promoting work; Abela could never have published his cartoons of El Bobo because they would be interpreted as a mockery of disability; nor Guayabero his ¡ni hablar!, for its songs full of allusions with double meaning and implicit vulgarity; from Benny Moré, as an intruder, they would have confiscated the instruments of his Banda Gigante; and even the untouchable national poet Nicolás Guillén would be censored for his “negro bembón.”

In Fahrenheit 451, the protagonist becomes a defender of books when he encounters some beautiful verses. When it comes time to select and train the inspectors for the Decree 349 “fire department,” ministry officials will face the following dilemma: If they do not supply them with the culture required to perform as critics they will do a sloppy job, but if they come to possess the necessary sensitivity and information to do their jobs, then they will be tolerant with the creators and that can be dangerous.

_____________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.