Cubanet, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 10 April 2018 — With the recent imprisonment of former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the regional left has just received another hard setback. In fact, it could almost be said that Lula’s fall from grace has been the most serious blow suffered by Latin American progressives in the midst of the relentless bashing that its leaders have been weathering in recent times.

Cubanet, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 10 April 2018 — With the recent imprisonment of former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the regional left has just received another hard setback. In fact, it could almost be said that Lula’s fall from grace has been the most serious blow suffered by Latin American progressives in the midst of the relentless bashing that its leaders have been weathering in recent times.

Lula is, without a doubt, one of the few heads of state of the left under whose government (2003-2011) extraordinary economic and social improvement was seen, reflected in a high rate of GDP growth, increases in exports, anticipated liquidation of external debts, strengthening of the national markets, significant decreases in unemployment, increases in salaries and the creation and diversification of microcredits, among other important reforms.

If Brazil reached a relevant position in the world economy in just eight years, and if ever the developing countries looked with hope at what was known at the time as “the Brazilian miracle,” it is largely due to the political talent and the economic reforms promoted by Lula, which explains his enormous popularity in his country and the considerable political capital which he still has, even in the midst of the judicial process – a corruption plot not yet concluded – that has landed him in jail.

But, along with all of Lula’s merits listed above is that other essential component of the best exponents of political populism: a mixture of charisma and histrionics that the former President, now a defendant, has deployed astutely, in the purest style of the television soap operas produced by his country, to manipulate the exalted spirits of his followers in his favor. Staying in the political game, despite everything, is one of the most common tricks of populist leaders, regardless of their ideological alignment.

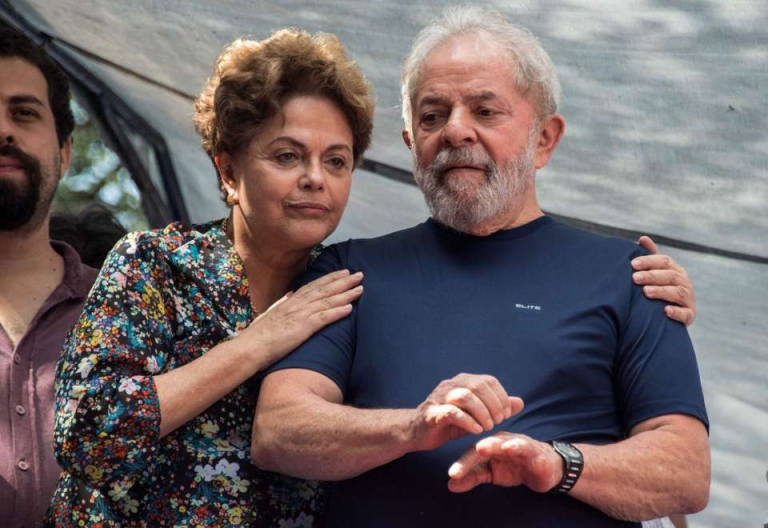

The hoax reached its climax precisely at the end of the 48 hours of the weekend in which he remained resistant – self imprisoned, it could be said – in the face of the order to surrender to the authorities to begin to serve a 12-year prison sentence, when, surrounded by militants of his own party (Partido de los Trabajadores, PT) and other allied parties – among which the everlasting scarlet shadow of the Communists could not be absent – Lula used popular sentimentality to invoke the memory of his late wife on the first anniversary of her death, with a Catholic mass that served to close a chapter in what promises to be an extensive and complicated saga.

Afterwards, before surrendering to the authorities, the beginning of messianism and megalomania surfaced in one who, now purified by his punishment, assumes himself as metamorphosed into the Illuminati of the poor, to harangue his enlightened discourse, with a mystical touch: “I will not stop because I am no longer a human being, I am an idea (…) mixed with your ideas.” And “in this town there are many Lulas.” Apotheosis of the peoples. The crowd cheered deliriously, tears flowed and hugs for the martyr abounded. Curtain down.

It is not personal. It is known that the defense of those who are condemned must be allowed, even from the guillotine, and that those who are hanged also kick about. However, as far as it has transpired, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was prosecuted with the corresponding guarantees under the Brazilian judicial system rules, and he is being convicted of corruption, not because of his political ideas.

Ergo, even though Lula’s downfall benefits his political adversaries, it was Lula himself who, in committing the crime, deeply harmed the PT and dirtied the “cause” of his followers. It is not, then, a “political trial,” as his regional leftist allies want others to believe, and some of them are beginning to fear they could also be splashed by this great mess of putrefaction.

Beyond all that Lula did well, no one is above the Law. After all, whoever is corrupt should be prosecuted and imprisoned, especially those who hold political office. It is true that, in good faith – and judging by the corruption scandals that are being uncovered in recent years among the political classes of any alignment – it would be said that, in order to imprison the dishonest public servants, prison capacities would have to be expanded rapidly, especially in Latin America.

In fact, the history of our region is so lavish in examples of political and administrative decay at all levels that this last uncorking, which continues to expose long chains of corruption and to implicate numerous high level politicians, should not surprise anyone. The novelty – and this, only to a certain extent – is that they are being judged, condemned and imprisoned.

We must not forget the case of the former Brazilian president Fernando Collor de Mello (who governed between March 1990 and October 1992) as the young politician who assumed the first presidency of a democratic Brazil. He won the elections in the second round – precisely against Lula da Silva – for the right-wing National Reconstruction Party, with the promise of ending the illicit enrichment of public officials.

Paradoxically, just over two years later, Collor de Mello was forced to resign because of investigations of corruption – acceptance of bribes in exchange for political favors – and influence peddling, followed by a Congress that officially requested his dismissal. A technicality in the court process prevented his being found guilty of political corruption, and that saved him from prison. However, Congress did consider him guilty and condemned him to eight years of suppression of his political rights. So far, Collor de Mello has not succeeded in his political career, although he has again attempted to venture into it.

Now, Collor de Mello’s asking his supporters back then to publicly demonstrate against what he called a “coup d’état”, seems to be part of a desperate recourse followed by presidents fallen into disgrace, beyond their political color. Years later, Dilma Rousseff took that same stance when facing her own destitution.

And these are only Brazilian references. We can also mention recent cases of fallen angels in other countries of the region, such as the left-wing Argentine president, Cristina Fernández – also said to be “persecuted politically,” the poor thing – or the right-wing Peruvian president, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski. It has been said that corruption is not an ideological disease, but a moral one.

And while the spiral of corruption continues to expand, dragging more and more prominent figures of regional politics in its dizzying cone, Latin Americans who are followers of one leader or another – or one party or trend or another – continue to show civic immaturity and the proverbial political infantilism.

So, instead of taking on the challenge of the moment and embracing the end of impunity as an essential principle that, without distinction or privileges, will reign over all public servants, they prefer to project themselves as if this were all a brawl between street gangs, where what really matters is not to prove one’s innocence but to accentuate the guilt of the adversary. It isn’t so much that “mine” is corrupt, but that “yours” is more so. And so it seems that we will continue to the end of time.

To paraphrase a well-known Cuban poet: It’s Latin America, don’t be surprised at anything.

Translated by Norma Whiting