![]() 14ymedio, Pedro Armando Junco, Camagüey, 24 August 2016 – The level of enslavement of a people is determined by the sum of freedoms that are restricted. Slavery and freedom are two ends of a scale that, as one side slants downward from the weight of the load on its side, its counterpart rises.

14ymedio, Pedro Armando Junco, Camagüey, 24 August 2016 – The level of enslavement of a people is determined by the sum of freedoms that are restricted. Slavery and freedom are two ends of a scale that, as one side slants downward from the weight of the load on its side, its counterpart rises.

I explained this to a high school student some days ago when he asked me if I agreed with the opinion of his grandfather, who told him that the Cuban people are suffering a modern form of slavery.

It took me a few minutes to answer his question. With teenagers and children one has to be extremely cautious when offering insights, and even more so when they ask questions based on the admiration and respect they have for us. What we express to them can become a dogmatic axiom for their lives. Children are intelligent and think for themselves and then seek out an adult who, for them, has their own opinion.

To dodge his query I answered with another questions;

“What is the basis for your opinion of the condition of a modern slave.”

“Many characteristics, prof (high school students call everyone who teaches them ‘prof’).

“For example?”

“The slaves of previous centuries suffered punishments that today wouldn’t work: shackles, whips, mutilation… But my grandfather says that we Cubans have lost rights that we enjoyed before the triumph of the Revolution and this is called modern slavery.”

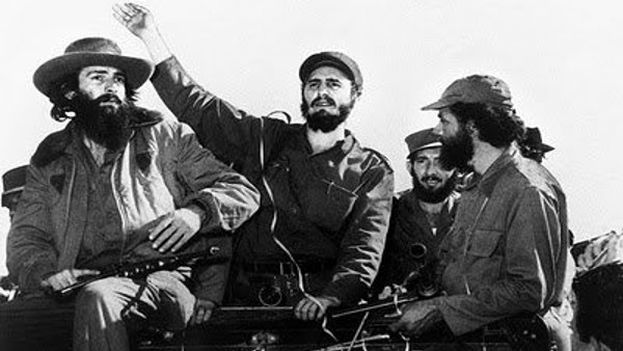

The young man’s grandfather had informed him that in January of 1959 more than 90% of Cubans were fidelistas – Fidel loyalists – and that people put signs on their doors saying, “Fidel, this is your home,” and that apparently the Maximum Leader took the offer seriously: he banned the sale of homes and confiscated more from everyone who kept things in their own names than from the rest. This he called “Urban Reform.”

Then he did the same thing with the haciendas and he called that Agrarian Reform. He confiscated the businesses, from the huge corporation to the last little mom-and-pop stands that supported thousands of proletarian families, stretching out their meager earnings. His grandfather had told him all this with a wry smile, saying that even the combs and scissors of the barbers did not escape confiscation. He didn’t know what to call this.

Possession of firearms was prohibited. Anyone who rebelled was shot or imprisoned. The labor unions were nationalized and the right to strike eliminated. The intellectuals were told “within the Revolution everyone and against the Revolution nothing,” leaving the concept ambiguous, but in a clear warning to those who tried to present personal arguments in publications and artistic works of any kind. The Cuban people, as a whole, were left stripped of their basic rights: without possessions, without arms and without the ability to show their discontent. The great ideologues of tyranny, especially Stalin, were always convinced that miserable people were not capable of rebellion.

This happened in the first decade of the Revolution. The results didn’t have to be waited for. The population, all of it, became the proletariat. The ration card arrived, a macabre Leninist idea from when people in Russia were starving to death in huge numbers. The coffee and meat quotas were reduced, along with those of other most needed items. Smallholdings were forbidden from selling their products to anyone but the State; the rancher who slaughtered a cow for family consumption could be punished with a long prison sentence; and so it was with most individual producers, creating the largest monopoly in memory in all of Cuba’s history, including during the centuries of colonial rule.

An official document was created for those who wanted to leave the country: the “white card,” controlled by the Ministry of the Interior and virtually unattainable by the common citizen except in exceptional cases. Cubans became inmates within the limited territory of the island, and all those who emigrated illegally, became a foreigner, stripped of their Cuban citizenship. An even greater limitation, was restricting the right of residents of other provinces to live in Havana.

In 1973, the right of the people to appear directly in court as an accuser was eliminated, regardless of their having proof of being the main injured party, regardless of the damage suffered, thus violating Article Six in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. “Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.”

In 1975, tens of thousands of Cuban were sent to fight in Angola. Refusing to serve as soldiers in this war was severely punished, especially among young people doing their compulsory military service. Members of the Communist Party and the Young Communist Union were stripped of their membership, and non-members were fired from their jobs. Thousands of Cubans lost their lives for a cause interfering in the affairs of another country that had nothing to do with them. The Cuban people still do not know the number of their compatriots who died in this adventure.

In 1980, homophobia reached its peak when a group of desperate people invaded the Peruvian Embassy; the Port of Mariel was opened for their deportation, and from there homosexuals, the disaffected and prison inmates were expelled to the United States. President Jimmy Carter’s humanist approach cost the Democratic Party the presidency of the United States.

At the end of the decade European Communism collapsed and Cuba faced a misery unprecedented in its history. The country coped by enforcing major restrictions on citizens, and there was even talk of communal kitchens and creating an indigenous style habitat. Luckily Hugo Chavez showed up with his oil in exchange for highly qualified Cuban personnel, rented out by the State, these “internationalist” collaborators – mostly doctors and other health care workers – received barely a miserable stipend from what Venezuela paid the Cuban government for their work.

Possession of an American dollar was punished by several years in prison. The consumption of fish was restricted to a greater extent and the ordinary citizen never had the right to try seafood, beef or other products from livestock farming.

Then came the new millennium, the high school student’s grandfather explained to him. Time did its work and the leadership of the country passed – apparently, the grandfather stressed slyly – to the hands of Raul Castro, the general president.

The general president opened some opportunities to the beleaguered citizens with his reiterative motto, “without haste, but without pause.” He removed the restrictions on travel, without completely letting go of the rope through a section of a decree. He allowed individual work, despite impeding the economic growth of businesses, and much less authorizing national citizens to make major investments, a privilege reserved only for foreigners. Holding of dollars was allowed, but every remittance received by an individual – from family or friends abroad – had to be immediately exchanged for a currency that has no value outside the country.

The Cuban people continue to drink at dawn a concoction that is not pure coffee. They put “chopped meat” on their tables with such a high proportion of soy it’s an effort to believe they are eating meat. They buy used clothes in the trapishoppings – a name derived from the word for ‘rag’ – donated by charities in other countries. They continue to be paid in Cuban pesos worth four cents each, versus the convertible pesos worth a dollar. They go on vacation to popular campsites along the riverbanks like aborigines, because places like Varadero are reserved for foreigners and senior leaders.

Their proletarian earnings don’t allow them to buy plane tickets to travel abroad and they lack the wherewithal to buy a car. The state monopoly swallows, as if into a funnel, the country’s scanty agricultural production at bargain prices. Popular dissent is not allowed or recognized, and when women go out into the streets carrying flowers in peaceful protest they are beaten, while the voices of dissenters, opponents and freethinkers are hermetically silenced in the mass media, and in the blocking of internet sites and radio broadcasts, which are considered enemies…

After listening to all the conjectures of the young high school student, I had no choice but to respond: “You belong to the new generation of Cubans that represent the future of the nation. You are young, talented and a friend of truth and wisdom. You have the right to determine through your own reasoning if the Cuban people are slaves or not; and, of course, the duty to work so that these injustices are eliminated.”