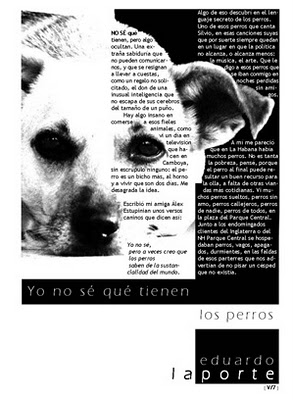

I Don’t Know What The Dogs Have

I Don’t Know What The Dogs Have

By Eduardo Laporte

I DON’T KNOW what they have, but something hidden. A strange wisdom they can’t communicate, that they are resigned to carrying on their backs, as an unsolicited gift, the gift of a rare intelligence that does not escape their brains the size of a fist.

There is something insane about eating these faithful animals, as I saw one day on TV that they do in Cambodia without any scruple: the dog is one more beast, into the oven and you eat for two days. I dislike the idea.

My friend Alex Estupinian wrote some canine verses which read:

I do not know

but sometimes I think that the dogs

know of the substantiality of the world.

I discovered some of that in the secret language of dogs. One of those dogs who sings Silvio, in those songs of his where fortunately there is always a place where politics can’t reach, or reaches under: music, art. What I say to those dogs who were with me in lost nights without friends.

It seemed to me that Havana had many dogs. There isn’t so much poverty, I thought, because the dog at the end can be a good resource for the pot, in the absence of other more everyday foods. I saw many stray dogs, dogs without a master, street dogs, no one’s dogs, everyone’s dogs, in Central Park Square. Along with their Sunday customers at the Inglaterra Hotel, or the NH Parque Central they were sheltering dogs, lazy, dull, sleeping, on the slopes of the planting beds where they warn us not to step on the lawn that doesn’t exist.

Those dogs were tired, defeated, had ceased to be dogs. They retained their wisdom — even though some people say that the dogs are stupid — but one day had renounced communicating it. Fifty is a lot of years, they’re thinking, and the disbelief was already great. The despair.

I appreciated as a legacy of defeatism in these dogs, in these animals of the Canaries of Tropics who didn’t worry themselves apart from the of no concern to depart from the blistering sun. I would see them gutted, sad, on the edge of eternal tears, on the sidewalks of the main streets, but also in the darkest corners of the Havana night.

In my runs through Central Havana I saw them, at times, but they didn’t frighten me because all ability to fight had been lost in them.

They were domesticated dogs that had never seen, so they had lost their essence in the animal kingdom. They lost their dog dignity, and it was a sad reflection of what they were. They say that dogs resemble their masters, and all those dogs, I say, were everyone’s and anyone’s, but most of all no one’s.

On the morning of May 1, 2009, fifty years after the Glorious-and-other-epithets Revolution of Comandante Fidel, I fell into the bourgeois act of letting myself go for a bike-taxi. It was hot, I was late, did not want to go alone. I took it, what do you want. The heat, I already said, was made of lead and the poor driver of that infernal gadget didn’t complain, but his legs were shaking like old elevator cables when he pumped the pedals. Is there equality? There will always be a guy who takes you to another, and that one will never be the first. There is always a dark dog that leave from a slap to not disturb us.

In Cuba I would appoint as president a bloody mongrel, surely things would be better. That morning, the liquid sun, strange liquid light that I would say I don’t know who (well, I think Roland Barthes of the southwestern French), through white streets like an unreal, surreal Andalusia, a dog appeared. A black dog, a Cuban dog, not an Andalusian dog. A real dog, not surreal, Dali no.

He looked into my eyes as if asking for help, as if to say “Hey, don’t go, listen, I’m here, help us.” We left him back there alone in that morning of forced party slogans and scheduled programs, of official smiles and national pride so well understood that many end up believing it until they go home and nothing happens.

I do not know what the dogs have, that dog black and silent, but when I see, here in Madrid, dogs jumping, gooey, sometimes aggressive, sometimes athletic, sometimes all of that all at once, I remember the Havana dogs, perhaps the saddest animals I’ve ever seen. Only Julia Núñez, when I visited at here home in Belascoaín, made me think that there were still dogs with rabies, but good rabies.

It was a funny sausage, but barking like a Doberman. I don’t like barking dogs, or dogs in my face, but this time I appreciated the fortitude on all fours. It was unlike any other dog, the dog of Julia Núñez. It was different from all those dogs thrown on the streets, in the sun, with no desire or to seek shade.

Sad, I think now, as the hippopotamus, the crocodile or the polar bear I’ve also seen in Madrid, but in the zoo.

August 8, 2010