Of all the check-in lines at the Barajas Airport there is one that is longer and slower. This is the Air Europe flight that leaves from Madrid for Havana. After Iberia cancelled its service to the Island, Cubans living in Spain have been left with only one direct option for their travel home. Here they are, carts loaded with suitcases, filled with presents they have accumulated over months for their families waiting on their native soil.

Two airline employees intercept the line at one point. They have a trained eye to detect tourists going on vacation. If you weren’t born in Cuba you can continue to the ticket counter to hand over your luggage.

But if you have the blue passport with the lone palm shield, then the treatment is different. For natives of the largest of the Antilles, airports are never easy expeditious sites through which they pass and continue on their way. Rather, each border is a heartache; each migratory process is twice as complicated as for other nationalities. The inspection of documents is slow, meticulous.

The Air Europe workers must guarantee that no Cuban boards the plane without permission to enter his own country. If they make a mistake, the airline itself will have to bear the cost of expatriating the passengers. So they take their time to make sure that the customer completes all the requirements before being letting him board the plane.

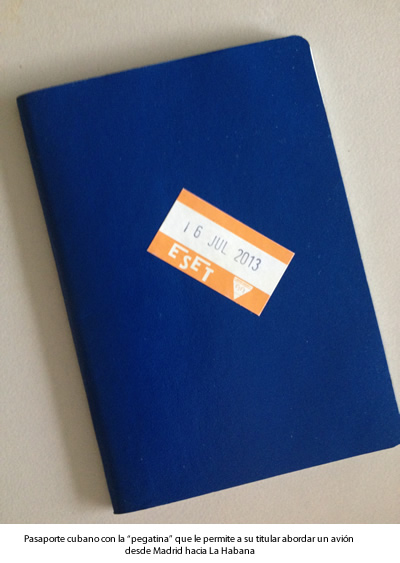

Most likely they have passed a special training, because they immediately look for the pages of the passport called “enabled”: authorization to enter for exiled Cubans. If everything is in order, they place a small sticker on the cover of the document. Without this scrap of paper you will never pass through the departure gate.

With the new Immigration Reform, which came into effect on January 14, the pre-flight inspection has become more complex. Now airlines flying to Cuba have to check if the passenger is within the range of a 24-month stay abroad allowed by the current law. For those who emigrated in previous years, everything is even more difficult.

The person could belong to the large group of those who are prohibited from entering the Island. Almost always for ideological reasons. Having made critical statements about the government, being a member of an opposition party, engaging in independent journalism, making a complaint to some international organization, deserting from an official mission, or being a target of the whims of power, are some of the causes that block the entry of thousands of our compatriots.

A few days ago, the case of Blanca Reyes, a member of the Ladies in White who lives in Spain, jumped into the headlines when she was denied the possibility of visiting her own country. With a 93-year-old father and a family she hasn’t seen in more than five years, Blanca requested an entry permit for the country where she was born. At the Cuban Consulate in Madrid the reply was terse: “denied.” So her passport was left without that other sticker of shame known as “enabled.” On the corresponding page there is no stamp on the watermarked paper that would allow her to return to Guayos, her little village in the central province of Santci Spíritus.

Without an “enabled” document, Blanca will not pass the scrutiny of those Air Europe employees, nor of any other airline flying to Cuba. For her, the longer and slower line at the Barajas Airport is an unattainable dream. As long as this absurd migratory restriction remains in force, she will have to stay — in the distance — accumulating presents and hugs to take to her family.

19 August 2013