Iván García, 13 December 2016 — The heat returned to the city along with the Reggaeton, the bustle and the alcohol. There’s nothing that bothers Danay, 26 years old, more than the drops of sweat running down her cheeks, mixed with the unbearable smell of kerosene of the old cars used as taxis in Havana, and the scandalous Reggaeton of Micha booming in her ears.

“Turn yourself around, tight and on your toes,” echoes the husky voice of Micha, an ex-slum dweller converted into a singer, coming from the audio equipment of Luis Alberto, 56, a self-employed taxi driver who drives a hybrid racing car 12 hours a day. It has a 1948 Chevrolet body, a German Mercedes Benz motor, a Japanese band-brake and a South Korean Hyundai gear box.

“I really missed the noise and the sandunga (a type of dance) of Cubans. Those nine days of mourning made Havana into one big funeral parlor. A magic trick. Rum wasn’t being sold, and if they saw you drinking a beer, you were pigeon-holed as a counterrevolutionary,” says Luis Alberto, while he tries to swerve around the collection of potholes on the streets of the capital.

Of the five passengers, no one mentions Fidel Castro. Nor the national mourning. Zulema says she got some bags of chicken at 24 fulas (Cuban Convertible pesos/dollars) each in a market at Carlos III and tells how she rations them out to her family.

“If I put them in the freezer, my children and my husband, who eat like pigs, will devour them in a week. I put five pieces of chicken in a little container inside the fridge. I keep the rest in a freezer under lock and key,” she explains to the passenger at her side, a sporty-looking black man who rides with his head shrunken into the back of the car and only knows how to nod, without commenting.

A young man with a bizarre hairstyle is living in another dimension. He listens to Jay Z with wireless headphones at elevated decibels. He doesn’t participate in the daily debate of the habaneros about the lack of money, food and a future.

He only looks out the car window and occasionally wipes the screen of his shiny Samsung Galaxy 7 with a cloth. Twenty minutes into the trip, Danay explodes.

The heat, the drops of sweat that are spoiling her makeup, the Reggaeton at high volume and the driver’s cigarette smoke, one cigarette after the other, like Marlon Brando in the Godfather saga, have gotten to her: “Please, can you turn down that music and stop smoking?”

The taxi driver looks are her like she’s an extra-terrestrial and answers, “Baby, although it doesn’t look like it, the car is mine. If you’re in a bad mood, you can get out. I bet anything that your boyfriend has left you,” and everybody laughs.

I’m left with this image. The laughing. In the last nine days, just to smile was suspicious. The habaneros were walking around like zombies, solemn and crestfallen.

When people talked about Fidel Castro, they threw out that automatic reproduction that many Cubans carry inside: “The greatest statesman of the twentieth century, the undefeated comandante, the man who escaped more than 600 attempts on his life by the CIA.” Something in that style. The commentaries were replicas of the official jargon.

People drank rum on the sly, the noise died down and a silence that brought more fear than calm spread throughout the whole city. Those who liked to tell tales about Pepito — the little boy who stars in so many Cuban jokes — in the corners, where Fidel Castro was the center of the joke, postponed the pleasantry until new notice.

The private bars sold only soft drinks, malt, fruit shakes and hamburgers. Neither mojitos nor wine. “You’re crazy, brother, if you think I’ll let the inspectors take away my license,” whispers the bar owner to a client. But before closing, he looks from one side to the other, and to those who remain in the bar he offers of drink of aged rum: “This is on the house, so you can celebrate what you want to celebrate.”

And so Fidel Castro’s death suddenly switched off the local customs, the proclamations in the street and that juicy and casual language of the Cubans. But Cuba is a game of mirrors.

Below ground they were betting on the numbers game and playing cards or baccarat in the clandestine casinos known as burles. The hookers worked exclusively door-to-door.

“In those nine days of national mourning it wasn’t wise to prowl around the outskirts of the private bars and discotheques,” says Zaida, who on Monday returned “to the fire.” “The clients were hungry. The mourning ended at 12 midnight on Sunday the 4th, and right away I began to have requests. Because the men were tense.”

Twenty-four hours after Fidel Castro’s ashes were placed by his brother, Raúl, inside an enormous rock that supposedly was brought from the Sierra Maestra to the Santiago cemetery of Santa Ifigenia, 900 kilometers from Havana, the chatting and the noise returned to the capital, and the drunks came back to uncork their bottles.

And the Reggaeton at high volume couldn’t be far behind.

Diarío Las Américas, December 9, 2016

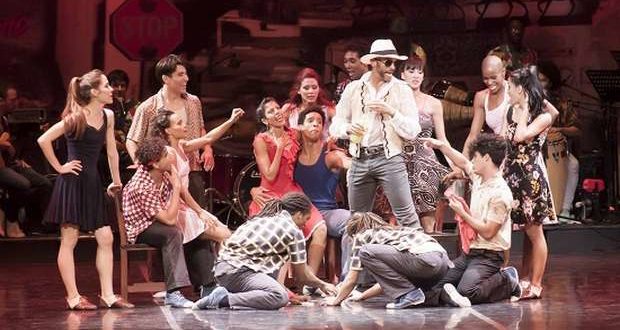

Photo: Once the nine days of official mourning for Fidel Castro’s death was over, the habaneros not only went back to laughing, singing, dancing and making jokes, they also resumed their cultural life. On the night of December 7, many attended the Gran Teatro de La Habana to enjoy the premiere of four works from the Acosta Danza company, directed by the Cuban, Carlos Acosta, who, in addition to the National Ballet of Cuba, has been a dancer in the Houston Ballet, American Ballet Theater and The Royal Ballet, among other important companies. One of the works premiered that night, taken by Ana León, from Cubanet.

Translated by Regina Anavy