![]() 14ymedio, Miriam Celaya, West Palm Beach | 20 December 2018 –Health professionals were not the first to suffer a slavery system organized by the Cuban government itself. Long before, and without the media noise caused by the controversial departure of Mais Médicos from Brazil, sailors have been the invisible victims of the same abuses on the part of the State.

14ymedio, Miriam Celaya, West Palm Beach | 20 December 2018 –Health professionals were not the first to suffer a slavery system organized by the Cuban government itself. Long before, and without the media noise caused by the controversial departure of Mais Médicos from Brazil, sailors have been the invisible victims of the same abuses on the part of the State.

This peculiar “legal” network of human trafficking is attested to by Rolando Amaya (a fictitious name), an ex-seaman with a long history. A Mechanical Engineer who graduated from the Naval Academy, Rolando worked for several years as a machinist in the merchant fleet belonging to the Mambisa Navigation Company, the large shipping company created by Fidel Castro to transport goods to and from Cuba, mainly based on the active trade that existed at that time with the now defunct Soviet Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (CAME).

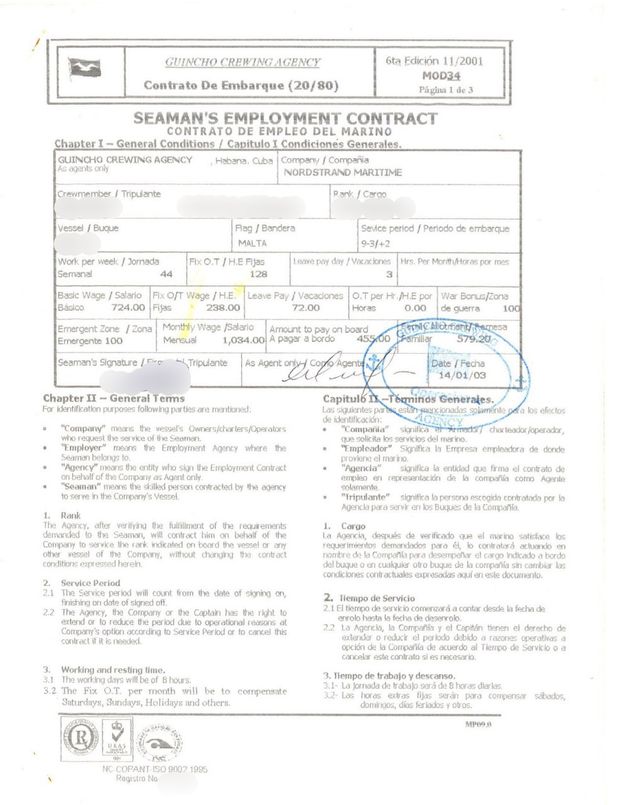

“In the contract, it is clear that my salary stated what I should earn, what I was paid on board and what was sent to Cuba as ‘family remittance’, which was the euphemistic term they used to call the money they kept and that ended up in the government’s coffers, or who knows where or who benefitted from it,” he tells 14ymedio, under the condition to keep his true identity secret.

“’Family Remittance’ was the euphemistic term they called the money they kept and that ended up in the government’s coffers, or who knows where it went or who benefitted from it”

Over the years, Rolando has kept some of the documents or contracts he signed with the state company Selecmar, in order to support his testimony and “so that the truth of the exploitation suffered by seamen is known.”

The “family remittances” and other discounts reflected in Rolando’s documentation constituted no less than 80% of the monthly salary paid by the foreign company for the sailor’s work. Therefore, both he and the rest of those contracted had access to the remaining 20%.

In the 70’s and 80’s, Cuban sailors were considered a privileged caste. On the one hand, they had the possibility of traveling around the world, while most of the locals lived the obligatory insular confinement. On the other hand, somehow, they managed to import (smuggle) clothes, shoes and other products of the capitalist world that the majority of the population could not even dream of.

In 1982, it was established that a minimum part of a sailor’s payment be made in foreign currency. Since then, recalls Rolando, the sailors began to see US $1 per day of navigation, a figure that has approximately doubled since 1985.

At the end of each trip, the hard currency was deducted from the salary in national currency and, if they did not spend that allowance, they could collect it in the form of “certificates” (chavitos) that allowed them to make purchases in several specialized stores to which foreign technicians also had access. These technicians were mostly Russians who resided in Cuba temporarily. These establishments were banned to the rest of the population and, in fact, they remained closed and with thick curtains behind the stained-glass windows, so that it was impossible to glimpse at those products to which common mortals had no access.

This payment system was maintained until the loss of the Cuban merchant fleet, in the 90’s, when, with the disappearance of the USSR and the Eastern allies, the subsidies suddenly vanished and commerce became dramatically depressed. Cuba fell into the deep economic crisis from which it has not recovered to date, and the merchant fleet that had been Castro’s pride became a burden, as useless as it was difficult to sustain.

Finally, after several failed experiments to try to save the ships – including a process of merger and separation of the national shipping companies, the ephemeral association with recognized entrepreneurs of foreign shipping companies and the creation of short-lived joint venture companies – the ships were sold to the highest bidder or destined to be scrapped after remaining idle for a long stretch of

However, that did not mean the total extinction of the state bureaucratic apparatus. Mambisa survived as a niche that would direct the lobbying and business necessary to achieve foreign exchange earnings. There were no ships, but there was still a very valuable resource: the sailors. Paradoxically, the shipping company, already without vessels, found a way to become productive without the need to invest to renew or maintain a very expensive and inoperative fleet.

There they were, within reach, desperate to earn money, hundreds of sailors who were “available,” as the unemployed are euphemistically called in Cuba.

“It is then that Agemarca (Maritime Employer Agency of the Caribbean) and Selecmar are born, among other agencies in charge of subcontracting Cuban sailors to foreign shipping companies. Of these, the best known among us sailors, was Boluda, a Spanish company named after its owner, Vicente Boluda, with whom the Cuban government still conducts business,” says Rolando, who – like many others – emigrated years ago and has not returned to Cuba.

In order to mask the violation of the rights of these workers before the world organizations, the Cuban Government launched a fraudulent ploy

“There were also contracts with other companies in Africa, the Caribbean and Europe. I know of some of my colleagues who were hired by those companies, who were as poorly paid as I was. In their cases, the Government received most of the contract money, although I don’t know the exact details, since I haven’t had access to their documents,” he explains.

To mask the violation of the rights of these workers before the world bodies responsible for ensuring their compliance – especially the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) as a qualified authority to represent seafarers before the International Organization of Labor (ILO) – the Cuban Government launched a fraudulent ploy.

The ruse consisted in having the seafarer sign a document, a copy of which he would not receive, in which he would state that he was earning a salary of between US $3,000 and $4,000 or more, depending on the position; that is, a figure much higher than what he really got. “This (false) document is the one that is shown to the international authorities that require it,” denounces the ex-mariner, who, although he emigrated over 10 years ago and has lost contact with his former work companions, has no doubt that “the exploitation continues.”

“It was customary to receive a some boss or company official who checked and corrected anything concerning the documents, inventories and everything related to the Quality System (by virtue of which each sailor must have updated the certifications that guarantee his ability to perform the work for which he was hired) who always somehow reminded us how bad the situation was in Cuba, the number of unemployed in the company, how poorly dressed they were, going through tough times, waiting to occupy our positions,” he continues.

“Many believed, and I dare say that even today they still believe that they are privileged even knowing that a significant part of their salary is being taken from them. It’s sad”.

This “worked as a kind of warning that you had to behave yourself or you would be out on the street.” Intimidation was always present, in a veiled or open manner. Many believed, and I dare say that even today they still believe that they are privileged, even knowing that a significant part of their salary is being taken from them. It’s sad,” says the former sailor, who is now almost 60 years old.

“One of the big problems that I had in the last years with the fleet was the age of the crew. It was an aging crew and, as far as I know, there was no way to replace them in the short term.”

Rolando believes that this, added to the fact that many of the sailors left Cuba in different ways and for different reasons, has led to the loss of trained personnel. “It has been a constant leak. Today I find some of them in the social networks, living in all parts of the world, much of that skilled labor that Cuba lost, and nobody stole it, Cuba lost it because of its exploitative politics.”

Translated by Norma Whiting

____________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.