I heard it said to a great man during a recent television interview: Asked about Cuba’s imminent future, the priest José Conrado, visiting Miami, responded that for him good news was approaching, hopes appearing on a complex horizon.

Suddenly, hearing his daring statement, I remembered something: I shared it with him 100%. I think that until that moment I hadn’t noticed precisely, but yes, I have a optimistic sense of good luck which lets me think of today’s Cuba — which I don’t like — with the tenderness of one who knows that soon he could begin to like it.

Said like that it might sound unintelligible. Ergo, it deserves explanation.

Perhaps the strongest pillar on which totalitarian regimes sustain themselves is immobility. Statism. Contemporary history offers us obvious testimonies: every time these centralized systems have tried to adapt themselves to new eras, modernizing through revitalizing perestroikas and glasnosts of survival, uncertainty has struck as the prelude to total collapse.

The reason, in my judgment, is primary: there is no way to mathematically calculate the impact of deep transformations in societies that have been, up to that moment, static. Let’s say that it’s a kind of “butterfly effect”: the think tanks know in a test tube sense what they would like to change — but, once outside it, events almost always are unpredictable and defy the keenest predictions.

Within this basic premise fits the question, for example: How will the political police fix relations beforehand with a man like Oscar Elías Biscet, made great by prison and once again free, once again battling in the streets of Lawton?

Or it could be: planning led to his liberation, until the moment they put an end to the burden that keeping him and dozens of prisoners of conscience inside Cuban prisons represented to international public opinion.

As a precautionary measure, like an astute political trick, they decided to debut a documentary series which “burned” undercover agents of State Security, whose purpose was — I can see it now — to prepare the tricky terrain discrediting an opposition which, inevitably, would strengthen itself with the release from prison of the dissident doctor and his companions in the cause who would not accept exile.

But now what? Oscar Elías Biscet has shown his usual position, his unwavering mood as a fearless man without restraints. His name has strengthened, it has grown as a national and international symbol… and now he has returned to the streets.

What will the establishment do this time? Will they put him in prison again when Biscet renews his public protests, his activism? Obviously not. At least, not for long. They would be dancing a political chachacha (little steps forward, little steps back) which isn’t even imaginable.

Strategic planning, the chess game of contention, is big to them this time.

The same applies to an even stronger reality: The layoffs forced by the updated economic model. Half a million put out on the street. Later, half a million more. The arduous big thinkers implementing the update of the economic model that will finally save the nation of hunger and destruction.

The question is: how to sustain social stability in a country where nearly 25 percent of the active working population are expected to be self-employed, without the existence of any mechanism that allows them to make a living?

Before leaving Cuba, a little over two months ago, I watched a reality: the amazing proliferation of snack vendors. But the mass layoffs still haven’t begun. To date it has started timidly, fearfully: It’s clear that it could not be completed before April as announced. But despite that, it will happen.

And how is that hundreds of thousands snack sellers subsist, peacefully? The markets are depleted, the products needed to make refined edibles are sold at science fiction prices, the snack stands spread like a modern plague.

Will it be enough, one more time? The fervent slogans, the documentaries with foul-mouthed heroes and the petty informers, to generate social stability once an element unknown on the Island until now — unemployment — is introduced?

On the other hand, how can they sustain docility and the massive support of a people who, unlike the delusional who survived the crisis of the nineties, already know of the world outside, and of the internal dissidents thanks to technology and the internet? These are modern times, times when brainwashing is hampered by independent blogs, by resonant voices from the streets of insular Cuba itself.

What do we see on the horizon, then? Let’s say a rarefied scene. It is so difficult to analyze and understand the actions of a schizoid. A government throwing temper tantrums, illogical, a government that releases — unconditionally now — prisoners of conscience who weighed too heavily on them from above, and on the other hand reprimands, by way of the usual pawns, brave women who are not intimidated by stones and excessive vulgarity.

A government that at times unblocks sites and blogs which, until recently, were closed to Internet users from the island, and then intensifies and refines their methods in the digital battle.

The reality speaks for itself: a landscape lacking balance or stability. A country governed, in theory, by a military man who is terrified of speaking, and in practice by an old man who promises the “Five Heroes” — held in American prisons — will be released before December 1st, though no one knows what year he’s talking about.

So we cross our fingers with, at times, very little (but growing) faith, and confirm the wise words of Father José Conrado: “Yes, I too maintain that this is the time to put in energy and good thinking, and to call on honesty and courage inside and outside of Cuba, in support of a democratization that, in spite of stubborn satraps, seems to hover in the distance moving slowly, but real.”

March 14 2011

Ill-Fated Trip

Ill-Fated Trip

“Don’t feel get too confident, I have other Agent Emilios.” That was the message — a bit old and worn out — sent out by State Security in their wrongly named report titled “The Reasons of Cuba” (broadcast by state TV on the night of February 26th) to the dissidence and anyone else who holds a critical stance against the government.

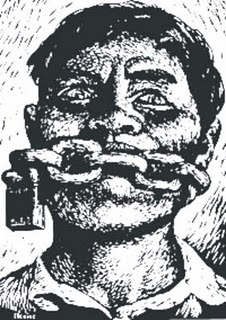

“Don’t feel get too confident, I have other Agent Emilios.” That was the message — a bit old and worn out — sent out by State Security in their wrongly named report titled “The Reasons of Cuba” (broadcast by state TV on the night of February 26th) to the dissidence and anyone else who holds a critical stance against the government. Between winter and spring, right when winter is about to finish and spring is about to begin, between the sprouting of branches and the rebirth of flowers, Cuba, the little island in the Caribbean Sea, hardens her chest and tries to conceal the pain of her wounds. She closes her eyes, she wants to cry, but she cannot. Her flowing stream of tears has dried. Everything becomes one: the suffering caused by death, and the hate and melancholy which divides her insides. She is chained. Once again, opportunism has deceived her and now she is imprisoned by others who have longed for power. They nail sad memories onto her, as well as the indolence of those who let her brothers die, those who couldn’t earn it themselves, of hunger.

Between winter and spring, right when winter is about to finish and spring is about to begin, between the sprouting of branches and the rebirth of flowers, Cuba, the little island in the Caribbean Sea, hardens her chest and tries to conceal the pain of her wounds. She closes her eyes, she wants to cry, but she cannot. Her flowing stream of tears has dried. Everything becomes one: the suffering caused by death, and the hate and melancholy which divides her insides. She is chained. Once again, opportunism has deceived her and now she is imprisoned by others who have longed for power. They nail sad memories onto her, as well as the indolence of those who let her brothers die, those who couldn’t earn it themselves, of hunger.

“I know the naysayers are coming now to pour cold water on my illusions,” a neighbor parodied in a tango tempo, on hearing a Cuban television report revealing a plan to flood with soybeans what has been taken over by marabou weed, where sugar cane was once planted in the fertile lands of Ciego de Avila. The long documentary had its premiere at the end of the last meeting of the full Council of Ministers and tasted of a long-hidden letter, revealed at just the right time.

“I know the naysayers are coming now to pour cold water on my illusions,” a neighbor parodied in a tango tempo, on hearing a Cuban television report revealing a plan to flood with soybeans what has been taken over by marabou weed, where sugar cane was once planted in the fertile lands of Ciego de Avila. The long documentary had its premiere at the end of the last meeting of the full Council of Ministers and tasted of a long-hidden letter, revealed at just the right time. In Cuba, we do not fear physical pain. Instead, fear is directed towards all the weapons of the government which they use to oppress. The most lethal of them: the law and its punishments. It is the perfect method used to deprive you of everything: your freedom, your home, your goods, and even your desire to live. The application is strict and severe, using legal norms to condemn you for trying to survive, to think, or to speak.

In Cuba, we do not fear physical pain. Instead, fear is directed towards all the weapons of the government which they use to oppress. The most lethal of them: the law and its punishments. It is the perfect method used to deprive you of everything: your freedom, your home, your goods, and even your desire to live. The application is strict and severe, using legal norms to condemn you for trying to survive, to think, or to speak.