Well-deservedly, my friends and I have been calling each other since last Thursday to congratulate ourselves. Some cheer from a distance, while others of us reach out our hands. Friends from different eras and generations: classmates from my university days; acquaintances I may have met on the streets with whom I’ve shared literary ideas at times.

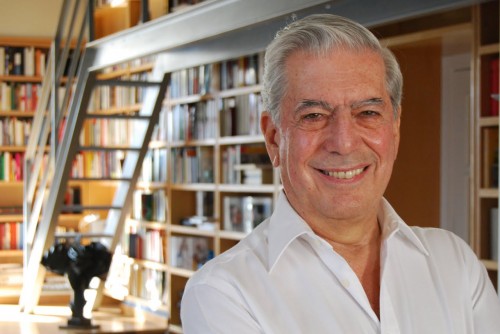

And I underline well-deserved, because congratulating each other for the Swedish Academy’s Nobel Prize awarded to Mario Vargas Llosa is an act of justice to ourselves: so much positive energy on his part, so many hours dedicated to his novels, so much saliva invested in rabid debates around his political ideas, we simply have to assume that this award is a prize for us as well, his readers.

Personally, I don’t hesitate to launch a categorical affirmation: nothing has influenced or determined my thinking more, my world-view on literature and artistic phenomenons; nobody dynamited my adolescent brain more with every type of libertarian, anti-totalitarian and cosmopolitan idea than this Peruvian Spaniard who today, for his work and by the grace of an elusive prize, is the most famous writer in the world.

Some of us had already lost hope. The Nobel seemed like a conflagration against him when, in the 1980s, right after publishing the incredible and insane novel, The War of the End of the World, Mario seemed predestined to hang it on his wall.

I was discouraged thinking about the lofty embarrassments for the Stockholm Committee which seemed as if they had never read Cortázar, Carpentier nor Borges, nor Kafka nor Joyce. And it irritated me still more to see that each year the Nobel Prize in Literature went to a figure even more exotic and unthinkable within the rich panorama of world literature. The Swedish professors seemed to have laid out the world map across a wide desk, point out the regions that had already received their awards, and randomly pick a writer from a non-awarded country.

The Nobel Prize seemed to be a novel prize: awarded to inconsequential writers who, logically, from then on would be enshrined. (The most baffling case in recent times was, without a doubt, that of 2004: the Austrian Elfriede Jelinek, author of love novellas written for dozing travelers, who seemed to have revived, with the astonishment of his expression, the American playwright John Steinbeck, winner of the prize in 1962, who said at the time that he himself could not believe it.)

And then, when it seemed least probable, someone picked up the phone at 5:30 in the morning in New York, and in broken Spanish it was communicated to the writer who was preparing for a conference for his Princeton students, that within 14 minutes the world would know his name as the winner of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature.

What was Vargas Llosa doing at that precise moment? In the interplay of ironies that sometimes God, or destiny, or karma constructs it is a surprising refinement: in the instant when his wife Patricia handed him the phone, Vargas Llosa was preparing a conference about Jorge Luis Borges, and was re-reading for the umpteenth time the novel El Reino de este Mundo, by the Cuban Alejo Carpentier.

For my part, what was I doing the instant that I learned my literary paradigm had just had his name inscribed among the unforgettable by the Nobel committee? I was sleeping soundly on a semi-London-like morning in my tropical Bayama, protected from the rain and cloudy sky, when the first ring at 7:30 in the morning forced me to emerge from my drowsiness, and assimilate the simple sentence with which my exalted friend said good morning:

“They gave the Nobel Prize to Vargas Llosa.”

After that, five more phone calls, at intervals of a few minutes, confirmed that it was not a tactless joke or a painful mistake.

Let’s just say: only those who are capable of loving literature with a sickening passion; only those who understand what it means to stay awake all night, and feel the anguish of not being able to comment to anybody at that time how fascinating the piece they have just read is, only they are capable of understanding the powerful link that is established between and author and his most faithful reader.

There are cases worth sharing. One of them is the story about a reader of Garcia Marquez’s found in Moscow, copying by hand on yellowish paper, a Russian translation of his One Hundred Years of Solitude, because she didn’t have money to buy that masterpiece and wanted to have it at home. Another one, which Julio Cortázar told: is about a young girl who, the night she decided to commit suicide, started reading his novel Rayuela. For some reason that desperate young girl wanted to end her life at a specific time at dawn, and while she was waiting she started to skim through the Argentine’s book. In a letter written later, that potential suicidal was thanking Cortázar for saving her life: his novel was able to let her ignore her depression, and the assigned time for her end arrived without her being able to let go of her reading.

As for me, I believe that reading Vargas Llosa is one of the best things that has ever happened to me in life, even though I haven’t had to copy him out by hand (but I have had to steal him with thousands of contraband devices), nor has he freed me from attempting suicide.

As for me, I believe that reading Vargas Llosa is one of the best things that has ever happened to me in life, even though I haven’t had to copy him out by hand (but I have had to steal him with thousands of contraband devices), nor has he freed me from attempting suicide.

The first book I read with his name on it, I mention today with love because it is a lesser novel: Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter. Afterwards, I embarked on a marathon until I’d read every one of his novels, searching through the bookstore catacombs to find some book by him, and practicing a kind of literary prostitution which led me to seduce, during my years at the University, a young librarian only because she let me take home Vargas Llosa’s books, which were not allowed to leave the library.

The last one I read — a gift from someone who loves me enough to know that man lives not by bread and remittances alone — so that from the United States to Cuba came The Lover’s Dictionary of Latin America, a collection of a huge number of articles on the issues surrounding our continent.

I think those who argue, ridiculously, of a presumed anti-Latin-Americanism, should review this compilation of more than 400 pages where an intellectual totally committed to his continent, is devoted to writing about its athletes, cities, eating habits, dictatorships, the common man and, of course, its literary history. Few writers know the roots of their origins better than this Peruvian who is a naturalized Spanish citizen.

Also for those who scream that Mario Vargas Llosa is the personification of anti-nationalist evil, they should ask themselves if there exists more proof about the destiny of one’s country, than to run for president as he did in 2000. Again, a historical irony about the novelist: he lost that election against someone who would later become the worst dictator in the recent history of Peru: Alberto Fujimori.

Today, Fujimori is behind bars for crimes against humanity, and Mario Vargas Llosa is the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

As I once wrote in an essay about his political views, to read Vargas Llosa in my Cuba of the parameters and the impossibilities, seems so much like an exercise in subversion, that searching through his entire work has a decidedly seductive appeal. At some point, Milan Kundera said that the one book banned under a totalitarian regime is more powerful and enticing than all the libraries in a free country put together. I think there is no contemporary literature more fascinating for Cuban readers than Mario Vargas Llosa’s.

But I am speaking not only of his novels. His monumental work also includes his work as a journalist and essayist, incredibly universal, extravagantly different, incredibly universal, that confirms in no uncertain terms what this man is really: an enslaved writer. A patient of the word who writes at seventy-four as if his life depends on it.

Into what subject of social, literary, political, biographical or advertising interest has the ex-presidential candidate writer not poked his nose into? Very few. His work is an Aleph of themes. I would dare to argue that wherever Vargas Llosa has not sniffed around with his particular visions and his incendiary words, where he has not opined with distinction or with insolence, where he has not generated a brilliant article, a personal chronicle, a linguistic analysis, or a well-reasoned debate; where he has not put people’s backs up, venomous sores of an emblematic hatred; on wherever that is, I don’t think there’s anything worth looking at.

On one occasion, I had the privilege to interview someone who knows him all too well: the Peruvian Franscisco Lombardo, who, with notable success has brought two of his well-known novels to the big screen: Captain Pantoja and the Special Services, and The City and The Dogs.

I asked him if Vargas Llosa was an almost moral obligation. His words to define the writer were categorical: “You can worship him or you can hate him, what you can’t deny is the admiration, or at least the respect due to those who defend what they believe, regardless of their doctrine, and knowing that they could pay a very high price for it.”

Mario has paid a heavy price for being consistent, above all, with himself. They never forgave him for supporting the Cuban Revolution, in its infancy, and then abandoning the triumphal boat and returning to be its eternal castigator. He has been demonized by the orthodox left, that cannot now forgive him for being a champion of liberal thought.

A journalist from Granma, not even worth mentioning, published the news of his Nobel yesterday, pointing out that he deserves an anti-Nobel in ethics. We know what it’s about: a poor journalist, an enslaved pen, who could not confess that he also reads his novels with devotion, on pain of becoming “available” — i.e. unemployed — now that a work place in Cuba is a privilege to be conserved.

I confirm with my own case what I once heard a notable writer say: the best thing we can point to about the Nobel Prize is that every year it makes a writer fashionable. With the satisfaction of a collection I chose, this time, Conversation in the Cathedral, and began to reread it with the same devotion with which I closed the final page five years ago.

I can’t think of no better way to honor this man, from my pride as a reader, and as a Latin American, than to dedicate a few more hours of my life to the novel it took him the most years to finish. And to feel that among all the millions of us readers who appreciate his dedication to the word, we feel the incomparable happiness — since last Thursday — of a huge dept repaid.

November 21, 2010