Maykel Gonzalez Vivero, Sagua la Grande, 20 May 2015 — My sister is telling me about what she just read: the unpublished autobiography of an elderly doctor in Camaguey. The memoir writer was an octogenarian when he wrote down his memories. The coming of electricity to the village of Cascarro, for example, figures in his review. A Galician installed the generator, pushed a lever, something trembled and there was light. I felt like I was there, my sister concluded.

I also enjoy reading memoirs. I value the survival of time as much as Proust. I’ve been obsessed with lost times since I was a child, when I would ask my grandmother to tell me something about “the olden days.” What came before, with its character of unknown certainty fascinates me, it motivates me more than now.

The old people of the family, settled in their present, are used to entertaining us with news from the past. Often, I guess, they’ve forgotten, and I remember a passage in Cintio Vitier referring to the mysterious capacity for forgetfulness. I, perhaps to my regret, can’t erase anything. Memory weighs me down, ties me to this forgotten city, to its disturbing cemetery of images.

Here’s an example that surprised my sister: inexplicably I remember what she was wearing almost twenty-five years ago, when we woke up on the morning to go to our grandfather’s funeral. I don’t remember how we made the journey, or what I myself was wearing. It was winter, we weren’t allowed to approach the tomb, and my sister, very small, was wearing a pleated skirt. Abounding in mournful red, it was probably a curtain or velvet crepe, like the brown of the jacket.

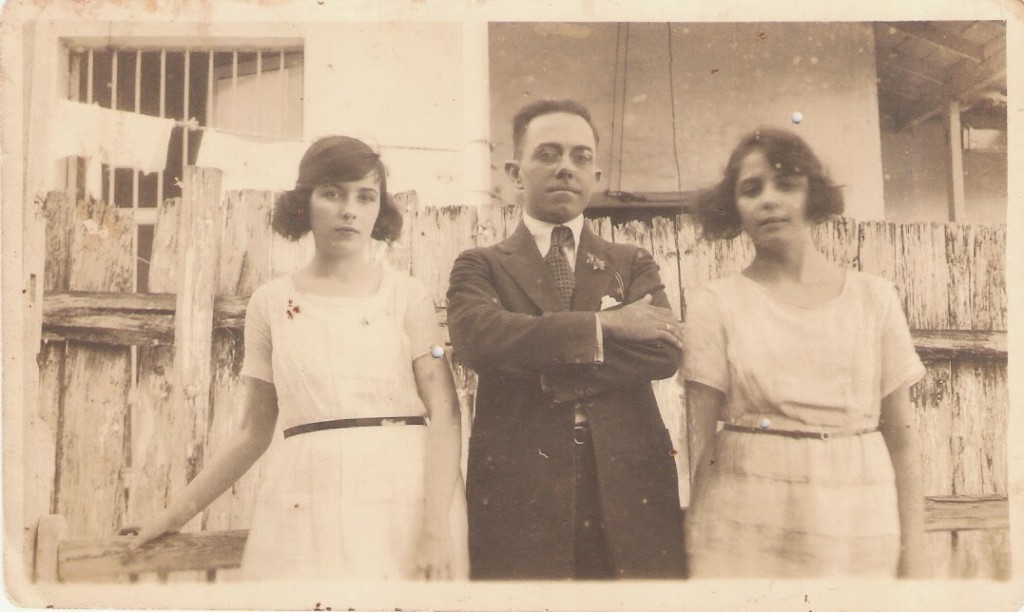

My sister reasoned, with alarm, that we know nothing of our ancestors. We go back a couple of generations and lose the trail. Unlike the elderly doctor, no one left memoirs. There is an explanation: we are descended from inevitably illiterate people. An old entry that our great-great-grandparents didn’t sign recording the birth of their children because they didn’t know how to write. Classified among the so-called “people without a history” that has confounded contemporary historians.

Appearing there, among the anonymous, doesn’t imply that they lived outside the vicissitudes of their times. During the famous strike of 9 April 1958, my grandmother hid her progeny under the bed. In the face of the anti-Machado revolution, in 1933, my great-grandfather forbade his offspring to leave the house. In 1896, after the Weyler proclamation, our relatives complied with the lethal order to leave their village. The site of our ancestors, I explained to my sister, was a hole, a hideout, an intrahistorical stronghold. The few exposed lacked experience in dealing with History and didn’t know what to do.

From the family forgetfulness and the biased stories, from the partiality of numerous historians, a late and peculiar compensation has come to us: my sister spent her teenage years collecting volumes about the Second World War; I assumed I had legitimate ancestors in the memoirs of Madame de Sevigne, Hans Christian Andersen, George Sand, Lola Maria de Ximeno and Renee Mendes-Capote. To Sand I owe the recovery of a memory, one word: orbiute. I thought there was no term to refer to the spots the sun leaves in your eyes after you have stared at its radiance for a while. Many summers I saw them. They stayed with me, unnamed. And it exists in Berry: orbiute. And it is not indelible, like memory.

Maykel Gonzalez Vivero, Sagua la Grande, Cuba

Maykel Gonzalez Vivero, Sagua la Grande, Cuba

“It was the night I desired and now I have it.”