A common school, half in ruins, half with children in uniform, with its Cuban flag and signs on the walls. The boys talk among themselves, then look with curiosity at the stranger, who takes photos of enormous homeless sites behind the surviving classrooms. Everything seems normal in that country schoolhouse. But there is a shadow. The stranger quickly quits with the photos. The last: some cement squares next to the door, “like a booth in a military unit,” he thought. He crosses the potholes of the road and approaches the wooden houses. They welcome him, give him water, talk about the sunshine and the plums. The stranger, who has already been introduced, happily drinks the coffee they also offer him, smiles, and thanks the lady and shuts up. It’s that there is a shadow.

Then, he asks the man of the house, an old man with a mustache, “Is it true that the elementary school, a long time ago, was a UMAP*?” He points at the half-boarding Batalla de Guisa school, whose kids have no idea what was suffered there forty-some years ago. The farmer stops smiling. He hesitates, stutters, speaks softly, looks at the floor. “Yes, yes… but no. I’m not looking for problems.” Someone says, “They took the people there to some banana groves to work.”

Other visits to the farmers around then, other evasions, “Yes, yes, some of that happened. One guy set himself on fire and the screams could be heard for miles. But I do not know anything else. “

One lady says, “There was a lot of damage. There were dungeons, there at the end.”

So I ask, in other houses, people who lived there, in the hamlet of Manolin, ten kilometers from the southern town of Cuatro Caminos, Camagüey, in the sixties, that time of so much luminous Revolution, and so many prison cells and firing squads — more than any time in the history of Cuba.

Those who respond say yes and open their eyes as if amazed at what they’ve just be reminded of. They know more or less that the collapsed schoolhouse was a UMAP camp, run by officers of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, and serious things happened to those interned there.

“What things?” and then they hesitated, “Better ask so-and-so, who lived closer.” And the faces of mystery, the silence, the evasions in the faces of the interviewed farmers tell me more than everything they can say to me: there are the silent screams of an abysmal shadow that hangs over the people in Cuba, not only those of these fields of Najasa, but so many in this country who live filled with fear of saying in public what they want and what they know.

And I write it of course: the biggest problem with the forced internal silence about the UMAP issue is not that there is discrimination based on sexual behavior today in Cuba and it remains in the minds of thousands of Cuban men and women and in the structures of leadership, nor that the one who manages this issue officially here is a member of the governing family — which stinks of nepotism — nor than they try to hide the past, among other reasons to avoid a settling of accounts, inopportune repentance and reparations for the victims. The worst is the infinite fear that still infects millions of people in this country, a logical fear induced from above which, while it exists, prevents Cubans from speaking freely of their desires, concerns and complaints, of their past, and even more seriously, of their present.

That grave mystery that the people around the little school that was UMAP remember fearfully, is proof. Where there are people afraid to speak there is no peace.

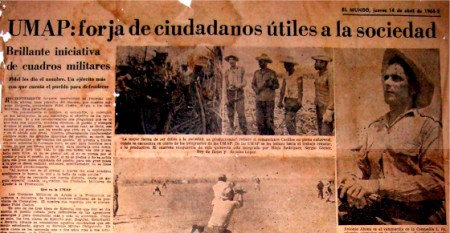

*Translator’s note: UMAP, “Military Units to Aid Production,” was a series of concentration camps where the regime imprisoned its “enemies” including homosexuals, religious believers, writers, artists, intellectuals and others.

18 May 2013