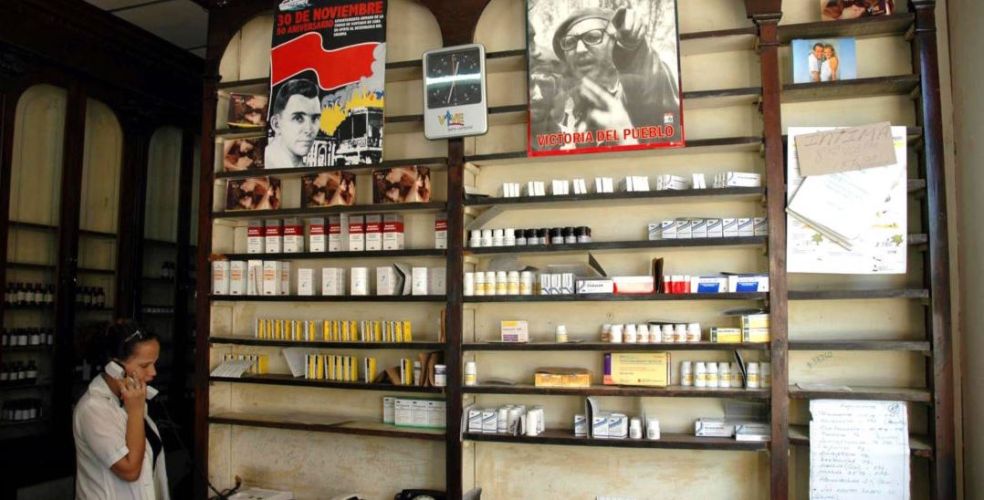

Cubanet, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 12 June 2020 – Another hot summer day has barely dawned in the city, but dozens of people are already gathered in the vestibule at the Carlos III Pharmacy in Central Havana. The day before, the drugs were “unloaded” and since quantity and variety of the assortment never meets demand, exactly every ten days an anxious human conglomerate fills the area and its surroundings for several hours.

In the past three to four years, drug shortages have become an increasingly tricky topic at this medical powerhouse. The impact of the crisis is such that neither the pharmaceutical industry nor the importing companies -both monopolies of the State- are able to insure even those drugs assigned to patients with chronic diseases, acquired through the Controlled Medicines Acquisition Card, popularly known as “the big card”.

“I warn you that only part of the Enalapril arrived, and antihistamines or dipyrone, medformin, or psychotropic drugs didn’t arrive either, so those who come looking for this already know it, and don’t bother to line up!”, warns one of the pharmacy employees, who has come out to face the crowd like a gladiator before lions. The answer, in effect, is a kind of collective roar. Discontent spreads.

Moments later the same employee returns to the crowded vestibule to report, with the same subtlety, about the great “solution” that pharmacies are going to apply to the shortage of medicines: “Shut up and pay attention here, so you can’t later say that you didn’t know!” Right after that, he makes an announcement that only half of the dose prescribed by the corresponding doctor will be filled for each card. And he ends with an absolutely irrational warning: “So save [your medicines]!”

The supposedly altruistic idea is that with this rationing of what has already been rationed, a greater number of patients have the possibility of acquiring part of the medicine that is required to treat their ailment. The bad news is that, in practice – and by the grace of the authority of the administrators of destitution – what this achieves is the multiplication of the number of people who cannot duly comply with what is indicated by a trained physician, and consequently, the risks of health complications that are derived, increase. Numerous of these cases include extremely serious events, such as cerebral or cardiovascular infarctions, hypercholesterolemia, hyperglycemia and kidney problems, just to mention a few.

Thus, the alternative to these shortages ignores such a basic principle that can be stated simply and mathematically: consuming half the dose equals twice the risk for patients. Because it so happens that there are no half-hypertensive, half-cardiac or half-diabetic cases. Health problems cannot be adapted to the inadequacy of the medicine market.

If it were not for the highly vaunted benefits of a Revolution that leaves no one helpless, we could imagine that we are witnessing a scenario of neo-Malthusianism, where the excess of population added to the increasing scarcity of resources imposes an inevitable socio-demographic selection: the weakest, the old, the ones with lowest incomes and the sick will be the decimated sectors and only the most solvent, strong, young and healthy will survive without further damage, be it or not- or not necessarily- a State policy.

It is obvious that, despite the accelerated aging of the population in Cuba and with that the increase in chronic patients with diseases related to advanced age, an effective government strategy was never devised to alleviate the stumbling blocks of the fragile national pharmaceutical industry or to protect the so-called “pharmacological groups by control cards”.

Going back in time and appealing to the long history of shortages on the Island, there are numerous drugs that have disappeared from the shelves since the 1990’s, never to return. Even those that were once available over the counter began to be sold by prescription only, a situation that remains to this day. Pharmacy supplies have never come close to what it was until 1989, despite frequent official promises for improvements or recovery of the industry.

Furthermore, the crisis has become so severe that eventually the official press has been forced to bring up the matter. Thus, for example, on 3 February 2018, the article On the Pharmacy Counter (by Julio Martínez Molina) appeared on the digital page of the State newspaper Granma, reporting that in 2017 dozens of shortages of drugs had been reported in throughout the country that year, and the persistence of “the absence of high demand pharmacological items” had been acknowledged, among them hypotensive, antidepressant, anti-ulcer medications and many more.

The BioCubaFarma association reported that the instability in drug deliveries was due to “the lack of adequate financing to pay suppliers of raw materials, packaging materials and expenses.” There was no lack of the favorite “blockade” among the causes for the pothole, which forced “the use of third countries to acquire equipment, American-made spare parts, chemical reagents, etc.”

Other data pointed to interesting figures: of the 801 drugs that make up “the basic picture” of Cuba’s drug demand, BioCubaFarma was responsible for 63%. In total, 505 medicines were produced by the National Pharmaceutical Industry and 286 were imported by the Ministry of Health (MINSAP); while of the 370 lines that were distributed to the pharmacy network, 301 were domestically produced and 69 imported.

Despite everything, explained authorities in the pharmaceutical industry, the critical situation “would change gradually” (would improve), up to the recovery of the production and distribution of medicines, which should take place around the first quarter of 2019.

But BioCubaFarma officials also suggested that the doctors carry some of the responsibility for not being sufficiently informed about the supplies of the drugs they prescribed to patients. “If the doctor has the correct information about the difficulties of a certain medicine, he should avoid prescribing it.”

The real problem, beyond this colossal simplicity, was, and still is, the almost absolute shortage of entire groups of medications, including antibiotics to fight infections or analgesics for pain relief which has caused many doctors – at the risk of being penalized – to recommend to their patients to arrange for their own medicines through family or friends overseas.

In 2018, during a presentation before the National Assembly, the then Minister of Public Health, Roberto Morales Ojeda, beckoned to “combat the misuse of medical prescriptions”, an exhortation that automatically led to the rationing of the doctors’ prescription books. After that, they would receive a limited number of these in order to tackle mismanagement among corrupt doctors and medicine smugglers, a business that had been confirmed for years and that grew in direct proportion to the decrease in supply in legal networks.

This was the rampant official strategy designed to eradicate the wide and deep hole of illegal maneuvers that let medicines slip through pharmacy networks, aggravating shortages and feeding the informal market. Simultaneously, a limit was also placed on the number of medications that could be indicated in each prescription, which – oh, paradox! – forced doctors to issue a greater number of prescriptions to each patient.

The result of so much nonsense was immediate: the drug smugglers diversified their strategies, but survived, while the insane rationalization of prescription books had a null, if not counterproductive effect, in the control of medications.

Meanwhile, more than two years after BioCubaFarma’s triumphant promises, and far from improving, the shortage of medicines in Cuba has deepened and is headed to getting even worse. Because at the end of the day it is not a medication crisis but a system whose disease has no cure.

Just around noon, the Carlos III’s Pharmacy had run out of medications. The line scatters, among whispers, complaints, and resigned faces. The curtain falls on a scene that will repeat itself in exactly ten days.

Translated by Norma Whiting