The divorce between the management of information and the Cuban reality is repeatedly striking, at least in the official press, a specialist in softening the country’s situation, exalting the allies of the regime, disparaging perceived enemies internal and external, repeating the hallelujahs of the government on reforms, blowing foreign correspondents out of proportion, as if there were a pact between the rules of Press Center in Havana and the agencies represented on the island.

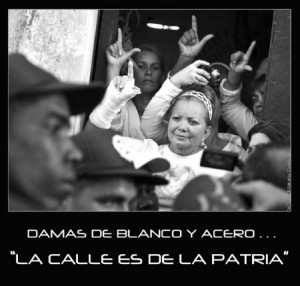

Sometimes we see on television the face of some peaceful opponents, especially the Ladies in White, who from now on parade without the presence of Laura — alma mater of the movement; the blogger Yoani Sanchez, independent journalist Guillermo Fariñas Hernández, lay communicator Dagoberto Valdes and other Democrats demonized as “agents of empire.” Such a reduction masks the repressors, protected by impunity, the tradition of terror and the indolence of the majority with regards to national events.

As if it were too little for a nation disconnected from the free flow of information and essential freedoms that encourage individual and collective development, not just that the government denies the emerging sectors of civil society, however minor, if not the accredited correspondents in Havana and even a sector of exile they associate with the “reaction of Miami,” as if such “reaction” was not the result of exclusion and intolerance of those who have, for half a century, been leading Cuba against wind or tide.

They speak contemptuously of the opponents as “hard line,” of “the crossroads of dissent,” the efforts of the Ladies in White marching in the streets despite “having no cause and without some of its best-known characters” as a result of the release of the prisoners in the spring of 2003. From Miami they comment, of course, on the increase in and continuing brief detentions, evidenced by the comprehensive report of Elizardo Sanchez Santa Cruz, leader of the Commission on Human Rights and National Reconciliation.

Independent of respect for opposing views, validated in the right to freedom of expression, as vilified in Cuba as freedom of press, association and others with they violate daily, I think those who speak of the hardline opposition within the island exaggerate.

There is nothing hard in insisting on meeting, celebrating the anniversary of certain events, demanding an end to police harassment, marching peacefully through the streets, giving interviews to Radio Martí and Cubanet and disseminating documents or proposals to the government. What happens is that the we have finally breached the “pact of silence” with which we are infected by the machinery of terror. Is the language hard? Perhaps, but less rabid than the campaigns in the newspaper Granma against the United States.

Since Batista’s coup in 1952, Cuban policy is marked by the hard-line. The struggle between the despot and the opposition ended with the flight of the tyrant on December 31, 1958, before the lawlessness caused by the bombs, the urban “executions,” and the guerrilla actions in the Escambray and Sierra Maestra.

Since Batista’s coup in 1952, Cuban policy is marked by the hard-line. The struggle between the despot and the opposition ended with the flight of the tyrant on December 31, 1958, before the lawlessness caused by the bombs, the urban “executions,” and the guerrilla actions in the Escambray and Sierra Maestra.

The revolutionaries of the time came to power through violence, shot thousands of people and imposed terror within their own ranks. Thanks to the terror and the alliance with the Soviet Union they eliminated republican institutions and wiped out those who confronted the new dictatorship of the Castros, which is still playing hardball to preserve the revolutionary pipe dream.

To play hardball means to engage in violence, at least for the government. The opponents know that after half a century of “revolutionary” rhetoric, economic involution and demoralization of the population, violence has no horizon. They do not confuse the media declarations with possible actions.

October 21 2011