Ivan Garcia, 11 July 2015 — On a leaden afternoon in 1960 that portended rain, René, 79 years old, recalls how a half-dozen militia members encased in wide uniforms and bearing Belgian weapons appeared at his uncle’s house in the peaceful neighborhood of La Víbora to certify the confiscation of his properties.

Ivan Garcia, 11 July 2015 — On a leaden afternoon in 1960 that portended rain, René, 79 years old, recalls how a half-dozen militia members encased in wide uniforms and bearing Belgian weapons appeared at his uncle’s house in the peaceful neighborhood of La Víbora to certify the confiscation of his properties.

“My family owned a milk processing plant that produced white and cream cheeses. They also owned an apartment house and a country residence. In two hours they were left with just the house in La Víbora and a car. Fidel Castro’s government confiscated the rest without paying a cent. Within six months they flew to Miami. Of course, I would view it well if the Cuban state were to compensate us for that arbitrariness. But I doubt it. Those people (the regime) have never liked to pay debts,” says René, who still lives with his children and grandchildren in the big house that had belonged to his relatives.

The Bearded One’s confiscatory hurricane was intense. Residences, works of art, jewelry, automobiles, industries, stores, businesses and newspapers were nationalized in the name of Revolutionary Justice.

Later, in 1968, the pyre of expropriations extended to the frita stands, neighborhood grocery stores, and scissor-sharpening shops. “They’d arrive with their dog faces and seize everything. Later, the owner of the little shop would have to sign a form attesting that the surrender had been voluntary. As far as I know, nobody protested. There was too much fear,” recalls Daniel, formerly the owner of a shoe repair shop.

Roy Schecher, an American born in Cuba, saw his rural property of 5,666 hectares, and a 17-room, colonial-era house in Havana, expropriated by the government; it is now the residence of the Chinese Embassy.

Schechter’s daughter, Amy Rosoff, told the publication News.com that when the authorities told her parents that their properties no longer belonged to them, they escaped from the Island in a ferry, carrying their hidden jewelry.

Schecter even paid all his employees before leaving, with the hope that he would return. He spent the rest of his life working in his father-in-law’s shoe store, and reminding his daughter that the lost properties would one day be reclaimed.

Cases like these number in the thousands. The United States government alleges that the military autocracy in Cuba owes $7-billion dollars to former property owners.

Several law firms in the US and Spain expect to wage a legal battle for their clients to obtain just compensation. Nicolás Gutiérrez, a Florida resident (but born in Costa Rica after his parents, Nicolás Gutiérrez Castaño and Aleida Álvarez, were exiled) defends the idea that some day the families whose properties were expropriated by the Cuban regime will be compensated.

And it is because Gutiérrez, a lawyer by profession, characterizes Decree 890, issued on 13 October 1960, as a “theft act” by which the recently installed government stripped all American companies operating on the Island of their properties, as well as the Cuban owners of many businesses.

So, too, the Gutiérrez family was bereft of their assets, including several sugar processing plants that were valued then at more than $45-million dollars.

The Gutiérrez-Castaño family’s holdings, which were among the most affected by the expropriations law, were built on years of work by Nicolás Castaño Capetillo, a Basque immigrant who arrived in Cuba at the age of 14 and with barely a third-grade education. When he died in 1926, “he was considered among the wealthiest men in the country, according to statements by his great-grandson to Iliana Lavastida, journalist with Diario Las Américas.

While the enterprises of hundreds of families or multinational corporations such as Coca-Cola or Exxon were confiscated, thousands of Cubans purged their defiance towards the Castro regime with long prison sentences.

Still remaining to be documented is the number of compatriots who were executed as a result of extremely summary trials, for having utilized the very same methods to which Fidel Castro resorted during his confrontation with the dictator Fulgencio Batista.

To be a dissident during the first years of the Revolutionary Government was a grave crime. Thousands of women and men suffered beatings and mistreatment in the Island’s prisons. The history of Cuban political imprisonment cannot be forgotten.

Now that the final reel of the Castro brother’s saga is rolling, the subject is once again relevant. What to do? Forget the past, or form a commission to investigate the arbitrary actions committed by the government?

Much can be learned from the experience of Eastern Europe. In the Spring of 2013, a conference took place in Miami in which Cubans from both shores participated, along with dissidents from the old communist Germany.

Reconciliation is not easy, warned Dieter Dettke, professor of the BMW Center of German and European Studies at Georgetown University, as well as Günter Nooke, dissident of the old German Democratic Republic (GDR), and later commissioner of human rights in reunified Germany.

A true rapprochement requires forgiveness as much as justice, but not revenge, Dettke said, pointing out that following the GDR’s collapse, 246 of its top-level functionaries were accused of various abuses. Around half were declared not guilty.

For reconciliation to happen, “there needs to be a sinner who repents,” said Nooke, who went on to state that the German government had agreed, following the reunification, to pay reparations to victims of the STASI, the GDR’s notoriously brutal security apparatus.

It is no use to attempt to turn the page as if nothing had happened. In its defense, the regime maintains that for reasons of the embargo, the United States should compensate Cuba with $100-billion dollars.

One might then ask if the olive-green autocracy plans to ask forgiveness for having lied to the Cuban people. Never was our opinion sought as to implementing is absurd political, economic and social strategies.

When the storm blows over, Cubans, all of us, should determine how we will negotiate our future without forgetting the past –keeping in mind that hatred obscures clarity.

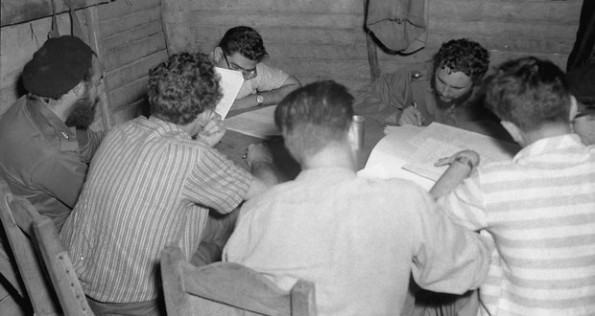

Photo by Gilberto Ante, 17 May 1959, La Plata, Sierra Maestra. In the country hut of peasant Julián Pérez: Fidel Castro; the economist Oscar Pinos Santos (seated in a corner, wearing glasses and a watch); and Antonio Núñez Jiménez, president of the National Institute for Agrarian Reform (at the left, wearing a beret), among other members of the Revolutionary Government; giving the final touches to the first Agrarian Reform Law, which would expropriate the large estates, and would become the first legal measure of a radical nature enforced by the bearded ones in power. On 4 October 1963, a second Agrarian Reform Law was approved, which according to some specialists marked the beginning of the agricultural disaster of Cuba (TQ).

Translated by: Alicia Barraqué Ellison