Cubalex, 16 February 2022

Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is clear:

“1. Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State.

2. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.”

Also the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: Article 12.4 [states], “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his own country.”

Article 52 of the Constitution of the Republic of Cuba recognizes as a right any person’s “freedom to enter, remain, travel, and exit the national territory, move or change residence, without limitations beyond those established in the law.”

Anamely Ramos González is not stateless, although it is what the Cuban state would like to convert her into.

She is a Cuban citizen. She has not made any legal arrangements that would result in the loss of her citizenship nor has she been informed of any resolutions declaring that.

She is a resident of the island. She has not been declared an emigrant, as she has not exceeded the uninterrupted 24-month period abroad as regulated in Decree-Law 302 Modifying Law No. 1312, the “Migration Law,” in article 9.2, nor has she lived abroad without complying with the existing migration regulations.

She possesses a valid Cuban passport, issued in her name.

Thus, Anamely is acting within the bounds of the law and it is the Cuban government that violates not only international law but the principle of equality and nondiscrimination, if not its own domestic legislation.

The aforementioned Decree-Law regulates a series of transactions required not only for the loss of citizenship but also a set of exceptions to deny entry into the country: Article 24. [These include engaging in:] prior terrorist activities, trafficking in persons, drug trafficking, money laundering, arms dealing or others which are prosecutable internationally; being linked with acts against humanity, human dignity, public health or prosecutable by virtue of international treaties to which Cuba is a party; organizing, stimulating, carrying out or participating in hostile acts against the political, economic, and social foundations of the Cuban state; when advisable for reasons of National Defense and Security; being denied entry into the country for having been declared undesirable or expelled and failure to comply with the regulations of the Migration Law, its regulations [sic], and the complementary provisions for entry into the country.

Anamely Ramos is not within any of those legal assumptions.

The Migration Law and its Regulations do not establish procedures for appealing the discretionary decisions of officials and for that reason they are not susceptible to being challenged in cases of abusive, discriminatory, arbitrary, irrational, and unjust application.

Cubalex reminds the Cuban state of its obligation to be transparent and protect and guarantee the right to access information; therefore, if a bilateral agreement exists between the two states or an agreement between American Airlines and the Cuban government, it must be published by virtue of the principle of transparency. This information is a matter of public interest.

Furthermore, they highlight that the burden of proof is on immigration authorities and that all acts that restrict fundamental rights must be argued in a reasoned and legally grounded manner, where the proof of damage is perfectly proven, which is nothing more than showing the real danger to Cuban society of Anamely Ramos González’s return to the country and showing that this damage is greater than the damage caused to her by the restriction of her fundamental rights, which because of the interdependence of human rights, inevitably implies the violation of others.

This is not the first time the state denies its citizens entry. However, this is different. In the cases previously documented by Cubalex, people had allowed the uninterrupted 24-month period to elapse without returning to the national territory (emigrants) and of residents in Cuba who were prevented from exiting when they tried to return to their country of residence. Currently, although Anamely’s migratory legal status is public and notorious, the state is responsible for leaving her defenseless and at risk in a foreign territory, given the irregular migratory status to which she is now exposed.

In any case, the motive for selective application of the law and justice is political discrimination against human rights defenders, independent journalists and artists, and in the majority of cases is led by State Security agents in collaboration with departments of Immigration and Foreigners (both belonging to the Ministry of the Interior).

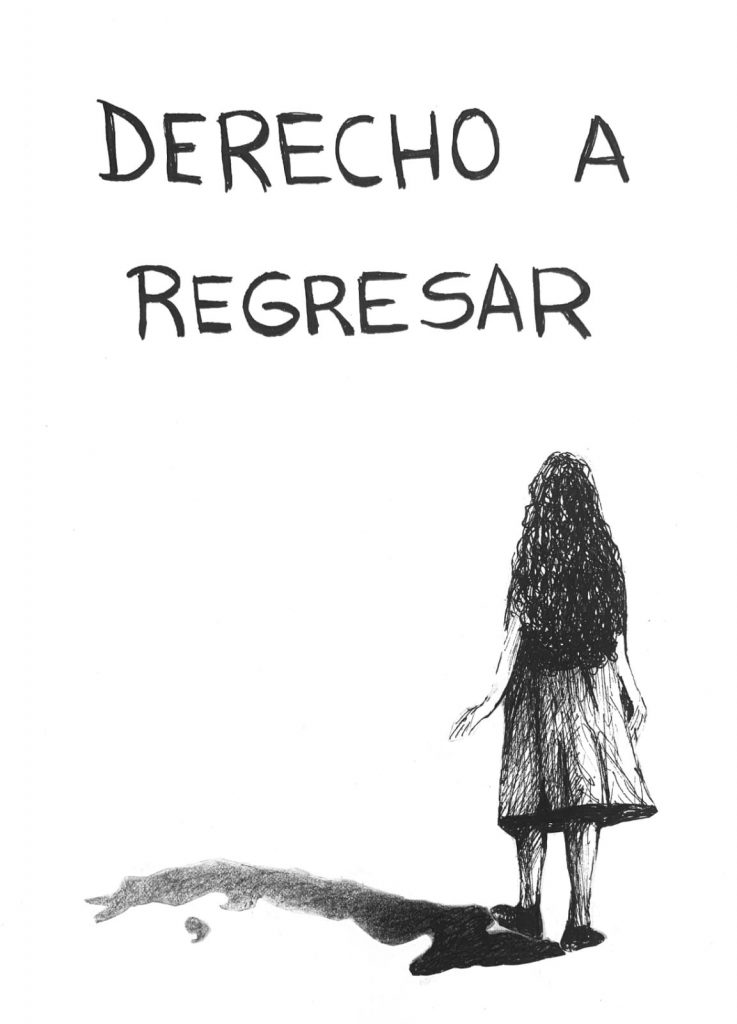

Of interest: The right to enter one’s own country

This entry, Cuba: The Forced Exile of Anamely Ramos, first appeared [in Spanish] on Cubalex.

Translated by: Silvia Suárez