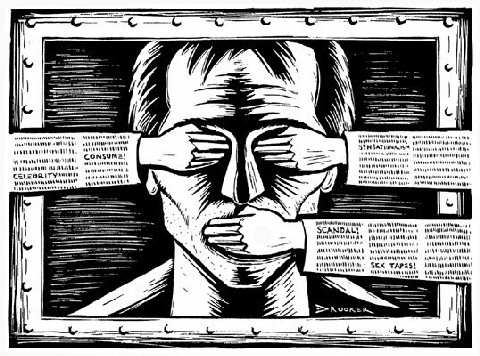

Cubanet, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 2 March 2018 – Recently, several media have reported the consummation of another attack by Cuban authorities on the freedom of expression. This time the jealous guardians of political correctness blocked access to the digital magazine El Estornudo (The Sneeze) – an entertaining and well-written journalism project – in what constitutes another demonstration of the totalitarian vocation of the island’s government.

Cubanet, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 2 March 2018 – Recently, several media have reported the consummation of another attack by Cuban authorities on the freedom of expression. This time the jealous guardians of political correctness blocked access to the digital magazine El Estornudo (The Sneeze) – an entertaining and well-written journalism project – in what constitutes another demonstration of the totalitarian vocation of the island’s government.

Thus, El Estornudo, is added to the censored list by the commissars of the Palace of the Revolution. A list, by the way, that is extensive, old and of varied tones, qualities and styles, but with one common denominator: narrating a reality that does not reflect the apologists – that is the “journalists” – of the Castro press.

For their part, the promoters of the magazine have responded with an editorial that does them honor: not only do they openly refuse to bow to the pressure of the Censor, but they declare that such arbitrariness “is not going to modify one iota the editorial line of our magazine nor is it going to make El Estornudo dialogue with the political power on the terms that the political power expects.”

This has been another chapter in the sad repressive repertoire that has been marking the general-president’s departure from the scene, a man who a decade ago was emerging as a possible reformer who would open a path towards relatively favorable changes for Cuba and Cubans.

However, far from making the promises of his initial speeches a reality, Raúl Castro’s last days at the head of the Government have been a clear step backwards that has been reflected particularly on two fronts: the unjustifiable crusade against the small and active private sector – where some minimal advances were being made in terms of the internal economy – and the new onslaught against the sectors of dissent or critics of the political system.

Faced with this reality and after almost 60 years of totalitarianism, it could be assumed that even the most optimistic Cuban would seriously question the health of human rights in Cuba. Especially of economic rights and the freedom of expression and information, so systematically and openly violated. But this is not the case, as evidenced by the interview recently granted by a young Cuban businessman, an emigrant named Juan Pablo Fung, to the news agency EFE.

Fung, great-grandson of a Cantonese Chinese who arrived in Cuba a century ago and settled permanently on the island, emigrated to China seven years ago thanks to a student scholarship. After finishing his studies he decided to stay in that country working for a better future which, obviously, he could not aspire to in Cuba.

Now Fung is about to realize a project dreamed up by him and for which he has been saving and working for the last three years: the production of “smart and free t-shirts” under the Dirstuff brand – carriers of “infinite and interchangeable messages” – soon to be on the market.

What is provocative about the case, however, are not the T-shirts themselves or the fact that they incorporate a personalized QR as a novelty – a technological resource that has already been used on the Island by independent activists – but the (very legitimate) aspiration of Fung to produce these “liberty T-shirts” in his native homeland in a future that, judging by his words, would seem close.

Fung also believes that this would be “the first private company in Cuba,” because “Cuba is changing” starting from an opening that began a few years ago and that will eventually lead to “the legalization of private companies” on the island.

What Fung evidently ignores, is that several years ago there were private capital companies on the island, not only those of foreign and “mixed” capital legalized by the State’s interests since the 1990s, but also those managed by Cubans “from inside.” It is just that the government does not define them as private companies but as “non-state forms” of economic management.

As for the promising “opening” that was announced precisely at the time that Fung left Cuba, currently it is in clear decline.

Nor is it clear whether Fung would invest as a Cuban “from within” or as a resident or Chinese citizen, that is, as a “Cuban émigré,” which for the purposes of the current socio-political and economic model “is neither the same nor is it equal.” In the second case – that is, as an exiled Cuban – the young man would find it impossible to invest on the Island, at least under current laws. Unfortunately, Cuba has not changed as much as Fung supposes.

But perhaps the most interesting thing about the theme of the shirts is the conflict they would spark in a political context as confrontational as that of Cuba. Fung declares that, although his product “advocates freedom of expression,” he does not want it to be politicized, because many people have been meditating on the Cuba issue “using the problems of politics as an argument and justification.” He does not want his T-shirts to become a political platform for these ends so that some profiteers can make money at his expense, which is also his legitimate right as creator and producer.

Being an expert in T-shirts is one thing, but in matters of politics, rights and freedoms the picture is different. Especially if we are talking about Cuba. It is enough to understand that if the Cuban authorities unleash such rage against independent and alternative digital spaces, to the point of censoring them and persecuting their animators – despite the insignificant Internet connectivity suffered by Cubans on the Island and the limited social reach of these media within the country – to know that the suspicions that the production and on-site commercialization of T-shirts carrying “free” messages which the explicitly apolitical Fung dreams of, are incalculable.

We can almost imagine the Central Committee’s Department of Political Guidance assuming the reins of production of “the first private company in Cuba” – Fung’s, of course – to flood the foreign tourism market with clothes, which would carry slogans such as “Commander in Chief, At Your Service!” or ” Fatherland or Death, We Will Conquer!” Or that other pearl that has been incorporated more recently into the official propaganda repertoire: “I am Fidel.” Dantesque. Even for such an optimist as Fung.

Because it turns out that Juan Pablo Fung does not believe that in Cuba “there is no freedom of expression.” For him it is only a problem of definitions around “a complicated issue.” A point on which the young man seems to agree with the censors in the service of Power, and another confusion for which we will have to forgive Fung.

In the end, settling in China can mean a discreet advance for a common Cuban in matters of financial prosperity, but it does not mean an advantageous change in terms of freedoms and rights. Perhaps that is why for Fung in Cuba “there is freedom of expression.” Yes, of course Fung, and “neither” in China.