Miriam Celaya, Cubanet, West Palm Beach, 28 June 2018 — A recent inquiry by colleagues Ana León and Augusto César San Martín about the expectations of several citizens, in the face of the constitutional reform, arouses reflection on some of the numerous gaps in the field of civic culture and rights ailing the Cuban population.

Miriam Celaya, Cubanet, West Palm Beach, 28 June 2018 — A recent inquiry by colleagues Ana León and Augusto César San Martín about the expectations of several citizens, in the face of the constitutional reform, arouses reflection on some of the numerous gaps in the field of civic culture and rights ailing the Cuban population.

Perhaps an illustrative example, which portrays the colossal work of citizen education that will have to be developed in an eventual transition scenario towards democracy, is the evidence of the almost absolute ignorance of the Law of laws by at least some of the Cubans questioned on the subject.

However, ignorance and even disdain regarding constitutional issues are not the only existing factors. In fact, illiteracy in legal and civil rights issues in Cuba is practically a congenital social disease, something perfectly understandable in a country governed for decades by autocratic voluntarism, through decrees and improvised regulations that commonly overcome — and even contradict — the letter, the spirit, the strength and the legal hierarchy of the Constitution itself. continue reading

Add to this that both the content of the Constitution and the laws, the courts that must enforce them and the institutions that must ensure order, exist in order to guarantee the privileges of Power, not the rights of citizenship, which determines that the subject (let’s call him the “citizen”) is constantly forced to commit crimes because of the imperatives of survival, and tends to alienate himself from a legal body that neither represents nor favors him.

Such legal confusion is also reflected in the opinions reaped by León and San Martín, where a segment of the participants, whom the authors define as “more radical,” believe that in the current constitutional reform process “everything must be changed, starting with the political vision from which the new document will be written,” while another imprecise number of testimonies show “modest aspirations,” of which only one is revealed: “increase in salaries and pensions.” A longing that would be related to a specific law in any case, but not to a Constitution.

Unfortunately, we do not know the number of subjects involved in the aforementioned journalistic survey, and we also lack other information about them, such as their ages, occupations and places of residence, which may be useful for venturing additional assessments. For this reason — scarce in testimonies and abounding above all in opinions issued by the authors — the text does not meet the expectations suggested by the title.

However, it is appreciated that León and San Martín bring up a topic as important as the preparation of a new constitution in Cuba. Especially if one takes into account the environment of conspiracy in which the new Statute is being cooked, the peculiar moment in which its drafting has been decided — marked by the transfer of the presidency of the country from the so-called “historical generation” to the “generational relay” — and the inexplicable fact that such a complex task is headed precisely by the ex-president, General Raúl Castro, who had the opportunity of convening a Constituent Assembly and amending the Constitution during the more than 10 years of his ill-fated mandate, but didn’t do it.

And since the corset that will truss the “new” Constitution from its inception was already announced — socialism’s irrevocable character and the role of the Cuban Communist Party as the leading force of society and of the State — it can be assumed that the novelties the new Statute brings are simple accommodations to disguise the subtle return to capitalism that has (illegally) been taking place before our eyes.

Clearly, the Constitution of Castro II will legitimize the highly vilified “exploitation of man by man,” which returned decades ago to successfully emulate the already previously sacramental (though never explicit) exploitation of man by the State; the privileged presence of foreign capital; the exclusion of Cubans and the perpetuation of power, all camouflaged under the innocent euphemism of “the Cuban model.”

So, if the official media have made reference to the debate by the National Assembly of Peoples Power of less conspicuous issues, such as equal marriage or revision of the Family Code, I do not think it intends to catapult Princess Mariela Castro towards future political stardom — in such a macho and homophobic country, much more is needed than the support of an army of gay revolutionaries to assume the presidency — but to create a smokescreen, a mere distraction that offers the world the image that, in effect, Cuba is changing and that it is more democratic and inclusive than many developed countries. From the UMAP* to the Palace of Marriages… Now that is the will to change, gentlemen!

As for the political and economic freedoms for Cubans, we already know that this option is vetoed. The olive-green mafia, now dressed in elegant suits and neat guayaberas, will move only the chips that certify their political interests, endorse their capital and maintain social control and “political balance.”

And in addition, they may astutely throw some legal crumbs that favor the minimal and undemanding private sector — a wholesale market, even if it is not stocked or offering better prices than the retailer, for example — in order to win their support and compliance. It is known that, as a general rule, the goals of long-term societies are not related to being freer, more prosperous and independent, but also to the petty aspiration of not belonging to the majority sector, the poorest members of the population.

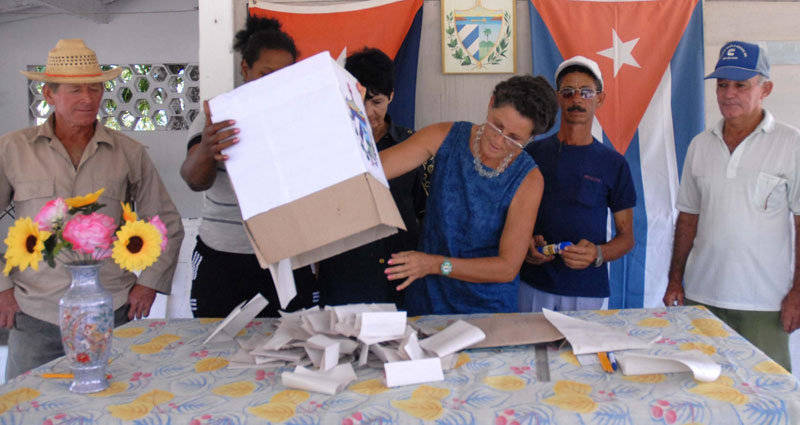

And assuredly, the remnants of the Castro regime and its political heirs will make their legalistic move so well that they will be able to show the world how some eight million idiots will go docilely to the polls to consecrate with their vote the perpetuity of the dispossession of their rights. We have already seen it before.

Except that (who knows?), the “masses” should understand that, this time, only they have the possibility to surprise us, and to use the power of their vote to say “NO” to a Constitution that is born mutilated and spurious. Maybe we are facing an opportunity and not a defeat.

Perhaps some opposition leaders, so engrossed in defending their own little egos, are missing a golden opportunity to show the world that there are a large number of Cubans who deserve recognition and support in their democratic aspirations, and — in passing — to clarify to the autocracy that they can no longer count on a unanimous and monotonous herd.

A tiny step, yes, but a step forward. It’s true that it would be an arduous task for leaders and activists to mobilize this time to get people to go the polls – rather than to boycott them – and to cast NO votes to oppose the conspiracy of Power. It is also true that this would not produce money or allow for personality cults, but on the contrary: it would cost capital and blur the leadership into “all of us.” For the first time the common leader would be the electorate. But, if what it really is about is the future of Cuba and of all Cubans, it would be well worth the effort.

*The UMAP, Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción, (Military Units for Aid to Production) were forced-work agricultural labor camps operated by the Cuban government during the mid-1960’s. Scant information available has characterized the camps solely as an instance of gender policing, though it was created for individuals who, for religious or other beliefs were not able to serve in the regular military units.

Miriam Celaya is a Cubanet journalist, resident in Cuba, who is visiting Florida

Translated by Norma Whiting