Archive photo

The economic and political sanctions imposed on Russian and Ukrainian leaders and officials by the United States and the European Union in response to actions on the Crimean peninsula do not appear to have been thoroughly thought through by the West.

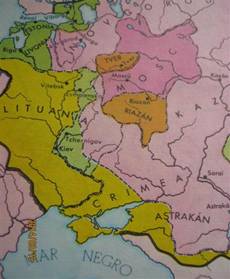

Without delving too deeply into history, we should remember that Crimea, including the peninsula of the same name, was once part of the Ottoman empire. It was annexed by the Russian empire in the 18th century during an expansion directed by Catherine the Great. It also included Poland and Lithuania, which— along with Russian territory — would many years later would make up present-day Ukraine.

The peninsula was occupied by the Nazis during WWII until its liberation by the Soviet army. In 1954 Nikita Khruschev, the first secretary of the Soviet Communist party, decided to transfer jurisdiction to the Republic of Ukraine. It was a time when the USSR included Ukraine as well as fourteen other Soviet republics. The Soviet Black Sea Fleet and its naval and air installations have been based on the peninsula for many years. The largest proportion of the population is ethnically Russian, followed by Ukrainians and then Tatars. In the 1990s the Russian parliament attempted to reintegrate the Crimean peninsula into Russia, but the effort went nowhere.

The latest events in Ukraine — namely the demise of Russia’s protege there as well as its almost assured admission to the European Union and subsequently to NATO — set off alarm bells in Moscow. From a defense standpoint, losing an ally like Ukraine would be terrible enough for Russia since it would leave its southwest frontier exposed to Western military positions. But to lose the Crimea as well would have been totally unacceptable since it would have posed a threat to the naval base for Russia’s Black Sea fleet, through which it gains access to the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The Russian president, who portrays himself as a leader intent on restoring Greater Russia and the country’s pride, could not act otherwise, lest it lead to domestic problems. He did what he had to do, to the delight of his countrymen.

The West, spurred by the rapid developments and upset by the action, tried to exert political pressure with threats, instead of pushing for a peaceful and reasonable solution, which could have included the non-interference of Russian in the current Ukraine and the acceptance of its government at the expense of the independence of the peninsula and its later reincorporation into Russia, if its the citizens so decided. When a government puts another government between a rock and a hard place, closing off any dignified exit, it must be willing to see it through to its ultimate consequences which, in this case, would have been to go to war, which it was clear to everyone that the West wouldn’t do; not for the Crimean peninsula nor for the Ukraine.

The situation created, the tensions and actions on both sides, poisoned the world political atmosphere and awakened the ghost of the Cold War, which seemed as if it belonged to history. If the independence of the Crimea peninsula had been negotiated, perhaps it would have later been used as international pressure against Russia demanding, in addition, their acceptance of the independence of Chechnya and Ossetia, autonomous republics situated in its territory, which have spent years demanding and fighting for it.

The same thing happened in the USSR at the beginning of the ’90s, when it ceased to exist. The Republics that made up the Union decided to become independent, as is happening now to Ukraine. The Crimea already forms part of Russia and it’s a fait accompli. The important thing now is to consolidate independence and ensure Ukraine’s political, economic and social stability.

21 March 2014