Yolanda Huerga (Radio Televisión Martí), April, 19, 2020 — It’s been 17 years since that April 19 when a group of Cuban artists and writers signed a letter supporting the imprisonment of 75 dissidents, the execution of three young men and life sentences for the other four, after they hijacked a boat with the intention of going to the United States.

The letter disclosed how “Message from Havana for friends who are far away” responded to the other document signed by dozens of intellectuals around the world, including traditional friends of the Revolution, in which they condemned the repression for crimes of opinion in Cuba and challenged the legality of “revolutionary justice.”

Radio Television Martí interviewed people about the gloomy atmosphere during those days of the Black Spring and the execution of the three boys who had been in prison only 10 days.

“The year 2003 was a definitive year, not only for policy but also for Cuban culture and society. It was the year of that shameful repressive act known as the Black Spring, which would initiate the most important social resistance movements of the opposition and the Ladies in White, and it was the year when three young men, who tried to flee Cuba in a boat, were deceived by being promised a fair trial and, finally, in an absolutely illegal and inhuman procedure, were executed,” noted Amir Valle, from Berlin, Germany.

Already in 1961, Fidel Castro had summed up his cultural policy in one sentence: “Inside the Revolution, everything. Outside the Revolution, nothing.” There were no alternatives. Creative people had to bend to that mandate because their survival depended on it.

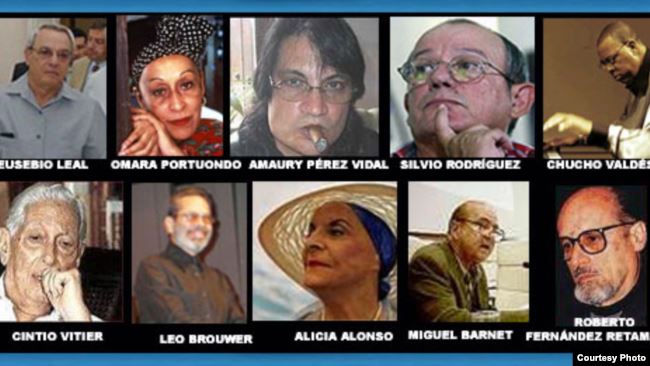

“Everybody I knew, from all strata of Cuban culture, everybody, thought that this was an aberration. They talked about it in small groups but never raised their voices, and many accepted this afront—the letter—in which personalities like Alicia Alonso, Silvio Rodríguez, Miguel Barnet, among others, not only defended the executions but also had the indecency to try to get thinkers from other countries to add themselves to this shameful support,” said Valle, the author of Los Denudos de Dios [The Naked of God].

The initial letter, signed by 27 noted figures of national culture and published in the official newspaper Granma, was followed by a call to all the members of the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC), the Hermanos Saiz Association, cultural institutions and universities throughout the country to follow the decision taken by Fidel Castro.

In the following weeks, Granma regularly published a list of those who added their signatures throughout the country.

In this respect, the writer and activist, Ángel Santiesteban said from the Cuban capital: “When the convocation opened, as my apartment was very close to the headquarters of UNEAC, many people came by my house to say hello, and I can say that even the most ardent defenders of the Regime confessed to me at that time that they didn’t agree with the imprisonment of the 75, and, above all, they were outraged at the execution of those boys.”

The Cuban Government stated that there was “budding aggression” and that the U.S. intended to invade Cuba.

“The majority justified signing the ‘Message’ by saying they didn’t agree with the invasion,” lamented Santiesteban, who already in 1995 had received the UNEAC prize for his book of short stories, Sueño de un día de verano [Dream of a Summer Day].”

The essayist, Carlos Aguilera, located in the German city of Frankfurt, emphasized that “this letter was a disgrace. On one side, the despotic State was imprisoning, assassinating, repressing. And on the other, a group of sycophants was encouraging all the terror of Castro’s policy. When, one day, they can ask questions and bring the guilty to justice, they will have to ask the Cuban intellectual claque why they not only signed the proclamation but also contributed to the crime and favored the dismantling of all critical positions, all spaces of reflection and discrepancy.”

However, more than the strong declarations by figures like Günter Grass, Mario Vargas Llosa and Jorge Edwards, it had a much bigger impact on national intellectuals, artists and writers. Some, openly on the left, like Pedro Almodóvar, Joan Manuel Serrat, Fernando Trueba, Joaquín Sabina, Caetano Veloso, José Saramago and Eduardo Galeano, harshly criticized the Regime. Even Noam Chomsky, in 2008, requested freedom for those detained in the Black Spring.

“Suddenly there was an apparent unity among colleagues of the Left and the Right on the world level,” said Valle. “It was a small seed that was sowed in the heads of many of us and that flourished some years later in the intellectual rebellion known as ‘Pavongate, or the Little War of Emails in 2007’. For this reason I think that 2003 marks a before and after, because not only did the events occur and not only was society moved but it also made very profound changes in the cultural and social policy in Cuba,” he added.

“No one should be in favor of the death penalty; human life is sacred in my opinion,” said the writer Gabriel Barrenechea, a native of Encrucijada, Villa Clara. “And it seems to me totally incongruent that a writer or an artist would support trials against freedom of expression. To deny this is to deny our essence as creators.”

Through the blog, Segunda Cita, Radio Televisión Martí contacted Silvio Rodríguez, and asked: “In April 2003, you signed the ‘Message from Havana for friends who are far away.’ Seventeen years later, do you continue supporting the executions?”

“I never supported those executions,” answered the singer. “I’m sure that none of the signers of that letter did. We signed the letter to close ranks with Cuba’s right to be sovereign. It was 2003, and when Bush launched an attack against Iraq, Colin Powell, inspired by the worst of Florida, said: ‘First Iraq and then Cuba’. Later he had to say it was a joke. I never quit defending my country from bullies and their friends,” said Silvio Rodríguez.

In an interview given to the Spanish newspaper, El Periódico, in 2008, the trova singer Pablo Milanés said that, unlike others, he refused “to sign a letter of support for the executions decreed in April 2003 and the penalties of long prison sentences for the 75 dissidents.” To the question of whether it was a matter of “pure opportunism” on the part of those intellectuals who signed the letter, Milanés responded, “Yes, and pure cowardice.”

Translated by Regina Anavy