![]() 14ymedio, Marcelo Hernandez, Havana, 20 April 2017 — The transport ministry (MITRANS) has issued a new provision that obligates Havana’s pedicab drivers to have visible identification that specifies the municipality where they can operate.

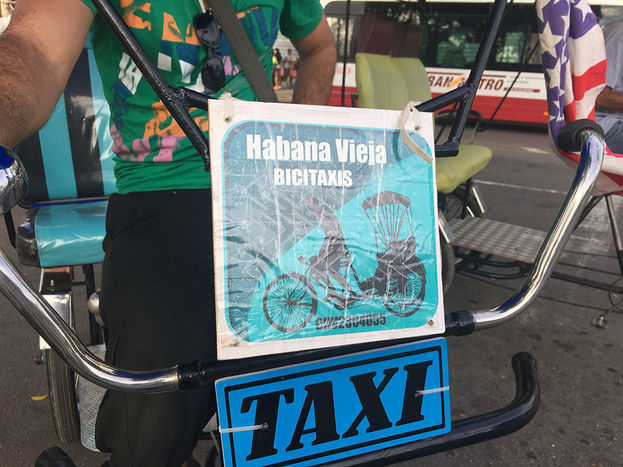

14ymedio, Marcelo Hernandez, Havana, 20 April 2017 — The transport ministry (MITRANS) has issued a new provision that obligates Havana’s pedicab drivers to have visible identification that specifies the municipality where they can operate.

The sticker carries the driver’s license number and the name of the municipality. An official calling herself Tamara explained to 14ymedio that MITRANS inspectors in the Central Havana district will ensure that “if you do not live in this municipality you can’t put the sticker on your vehicle that authorizes you to operate here.”

The office is located in a half-wrecked building on Zanja Street with a poorly painted façade and tree growing out of it, from a seed that fell into a crack in the building.

Sheathed in her blue MITRANS inspector’s uniform, Tamara barely looks up from the papers she has in front of her on her desk, to clarify that if you don’t have a license, don’t come. “In addition, they have to bring the acrylic.”

The situation of transport in the capital, traditionally complicated, has become chaotic in recent times due to fuel restrictions and other bureaucratic measures that have affected private taxi drivers. Driving a pedicab is not very profitable, since drivers usually charge 1 Cuban convertible peso (roughly $1 US) for relatively short stretches, but unlike the so-called almendrones– the shared fixed route taxis whose name comes from the “almond-shape” of the classic American cars used in that service – they do not run on a fixed route and take the customers “to the door of their house.” Most of them are young people without a defined profession who work for an invisible boss who owns the equipment, and whom they have to pay more than half of what they collect daily.

A tour of the pedicab stands where the drivers usually find their customers, found that only a few drivers were displaying the identification. Very close to Chinatown a young man barely 20, who identifies himself as Yuslo, gives the impression of not feeling threatened by the new measure.

“I am a Palestinian* from Mayarí Arriba, I rent in a room in the Cerro district and I circulate around Old Havana. I don’t have an address in the capital on my identity card or license, I am a pirate who fights to survive. If things get ugly I make the sticker my own way and put it on the front of the bike,” he explains resolutely.

A little more measured and optimistic is Alberto Ramirez, who despite being in quarantine still has the energy to live from his physical effort. “We are accustomed to occasionally ‘inventing’ something of this type. A few days later the fever passes and no one remembers anything. I have my sticker to work in Old Havana because I have been living there for more than 20 years in a state shelter, but if a client asks me to take him to Coppelia (outside his district), I’ll charge him what the trip is worth and take him.”

While Alberto talks, a colleague at the pedicab stand keeps making gestures of disagreement. Finally he intervenes to say, “They are the ones who call the shots and do what they want. You don’t have to be an engineer to realize that this measure is a barbarity. It’s fine to have control but if no one cares where a minister or a chief of something lives in order to work here or there, why do they have to worry about where the unfortunates who survive from our work live? There’s no one who understands it,” protests the pedicab driver.

Without taking the time to answer another question he gets on his bike and in the worst possible mood concludes the conversation. “I’m going home. I don’t feel like working.”

*Translator’s note: Havanans call Cubans from the provinces who settle in their city “Palestinians” – a reference to the fact that without a resident permit, they are “illegals” in the city.