Ivan Garcia, 15 February 2018 — He’s like a character out of a dark novel by Pedro Juan Gutiérrez. He turned 30 on December 2, 2017, and the life of Luis Manuel Otero has been marked by survival.

He still remembers the 12-hour blackouts when he was a kid, in the middle of the Special Period. The empty, grimy pots and the unmistakable color of El Pilar, his neighborhood in the Havana municipality of Cerro.

The section of Romay Street, from Monte to Zequeira, doesn’t even go 100 yards. It’s narrow and unpaved. The houses are one-story. The only building that had three floors collapsed from lack of maintenance.

The house of the Otero Alcántara family, at number 57, is typical of early 20th century construction, with tall pillars and large windows. Throughout the night, women are sitting in the doorway, gossiping, while the men take up a collection to buy a liter of bad rum, steal detergent from the Sabatés factory or kill the boredom with a game of baseball in the old Cerro Stadium.

Luis Manuel grew up there, on a poor block full of tenement housing, where drugs and psychotropics are a rite of passage, the young people are abakuás (devotees of the African religion) and problems are solved with guns or machetes.

His father, Luis Otero, used to be a dangerous guy. He always was mixed up in legal problems, and jail became his second home. In prison he became a welder, and the last time he left the Combinado del Este prison, he promised he wouldn’t return.

María del Carmen, the mother of the artist and a construction technician, is a “struggler,” like most Cuban women. When she was pregnant with Luis Manuel, his father was in jail.

“Let’s see what happens,” she said to herself. She acted as mother and father for a long time. Perhaps because of maternal overprotection, she opted to bring him up behind closed doors at home.

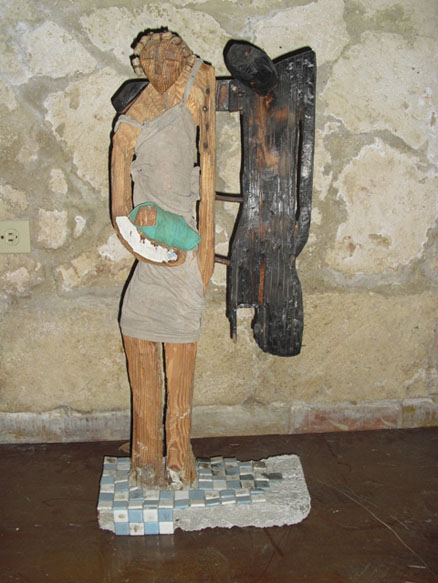

Luis Manuel Oteros, a mulatto with an adolescent expression, gestures with his mouth and mentions that to escape from that reclusive life, “I made my own wooden toys. I had this gift from the time I was little. I don’t know who I inherited it from, because there’s no other sculptor or visual artist in my family. I spent hours and hours talking alone. I created scenes and imaginary characters. And from childhood, I vowed to be someone in life,” he said, seated on a wooden stool and leaning against the wall of his studio on San Isidro in Old Havana.

Then he went to school. “I spent primary at Romualdo la Cuesta and secondary at Nguyen Van Troi. I always had a piece of wood in my hands. My grandmother was working in Viviendas, and this was during the years when Cubans decided to emigrate. The State confiscated their property, and many people gave her things, used clothing and household appliances. So we had a washing machine, but I hardly ever had shoes, only one pair that almost always was torn. I went to school wearing hideous boots or plastic shoes,” remembers Otero, and adds:

“I was nine or 10 years old, and like all the kids in the area, we were looking for a way to make money to help out at home, to buy things or go to parties on weekends. A friend and I from the neighborhood decided to remove bricks from buildings and abandoned houses. At that time, recycled bricks were selling for three pesos on the black market, but we sold them for two. One afternoon, my mother caught me doing this and beat me with a rope all the way home.”

Before getting involved with visual arts, Otero spent four or five years training as a mid-distance runner on a clay court at the Ciudad Deportiva.

“I wanted to get ahead. I appreciated the discipline and commitment of sports. I ran the 1,500 and 5,000 meter-dash. I had prospects. I was training hard to reach my goal: to escape from poverty. But in a competition in Santiago de Cuba, in spite of being the favorite, I came in fourth. I wasn’t programmed for losing. So I decided to study and try sculpture and the visual arts.”

In his free time, he and a friend sold DVDs for three convertible pesos in the streets of Nuevo Vedado, and he made wood carvings. “A cane that I made ended up at a workshop that Victor Fowler had in La Vibora. I was 17 and started to become serious about sculpture. I attended many workshops. I always had a tremendous desire to learn, study, better myself. I’m a self-taught artist and a lover of Cuban history. I also slipped into the courses offered by the Instituto Superior de Arte. It was an exciting world.

“When I went home, I went back to reality. Mediating the fights and blows between my father and mother or the problems that my younger brother had,” remembers Luis Manuel, leaning on an ancient VEF-207 radio of the Soviet era, dressed in mustard-colored pants and a white pullover with the faces of the Indian Hatuey, José Martí, Fidel Castro and the peaceful opponent, Oswaldo Payá Sardiñas.

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara had an exposition for the first time in a gallery in Cerro, on the Avenida 20 de Mayo, in 2011. “I called it, ’Heroes are no burden.’ It was wooden statues of men from the trunk up, without legs. I dedicated it to the soldiers who were mutilated during the war in Angola. I personally invited a dozen combatants who had been in the struggle. I was tense, waiting to see what the reaction would be, but the show was very well received.”

He had already begun his political activism by then. “I had too many questions without answers. I saw that the expectations of society were not taken into account. I had no way out. Everything was a bunch of blah, blah,blah, speeches with no meaning. In private, the majority of artists recognized that things should change. Cuba is crazy. It’s also true that there’s a lot of opportunism in the artistic world. Hustling is normal in this environment. I saw that something should be done,” commented Otero, in a deliberate tone.

And he decided to work on his art with a new focus. December 17, 2014 was a date to remember. “That noon I was amazed to see Raúl Castro and Barack Obama on television. I felt that a new epoch was beginning. That the worst was behind us. That a stage of reconciliation and national reconstruction would begin. That was the feeling among most people: that there would be more negotiations, that finally we would have a better level of life. People had tremendous hope. It was a dream that was contagious.”

But the Regime put obstacles in the way. The greatest optimism passed to the worst pessimism. The resumption of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the U.S. was purely an illusion. More press headlines than concrete initiatives that will improve the quality of life of Cubans.

Luis Manuel Otero remembers that Rubén del Valle, the Vice Minister of Culture, “said, and no one told me, I was still here, that they were going to need several shiploads to be able to sell all the works of Cuban culture. The feeling that many artists had was that in the biennials and events, Americans would start buying valuable artistic pieces. I wanted to make something, to be in fashion. My sin was in being naive.”

Barely one month before, on November 25, 2014, Otero performed downtown on Calle 23, on the Rampa, which was noted in the international press. “At that time I had an American girlfriend. The intention of the performance was to ask her to marry me at a wifi site that had become popular, with no privacy and people screaming and asking for money and other things from their families. I did a stripper act on the corner of L and 23, accompanied by two mariachis. On that occasion, perhaps out of surprise, State Security didn’t interrupt me.”

A little after this, he broke up with her and started courting Yanelys Núñez, who had a degree in art history, and a main piece in her present project at the Museum of Dissidence. Otero is like a box with push-buttons: hyperactive, suggestive and creative. In the middle of a conversation, an idea of his next performance came to him.

“Sometimes I take two or three days tossing around an idea for a work. And it’s in the middle of the night that a concrete idea comes to me. Then I wake up Yanelys and we go to work. With the last one, the Testament of Fidel Castro, it was more or less like that. The George Pompidou Center in Paris asked me for a sample that I was going to make. What occurred to me was the testament of Fidel inside a bottle of Havana Club rum. I implied that at the end of his life, he repented of all the harm he did,” emphasizes Alcántrara.

Right now it’s not at all clear to him. But perhaps before, during or after the succession directed by Raúl Castro, he will start a new project. April, Luis Manuel speculates, could be the month he gets lucky.

Translated by Regina Anavy