HAVANA, Cuba — For almost the first three years of his regime, Fidel Castro was not interested in Cuban intellectuals. He did not forgive their passivity during the years of revolutionary insurrection. They had not put bombs in the street, nor did they engage in armed conflict with the previous dictator’s police. Even those who lived abroad did not do anything for the revolutionary triumph. He never forgave them. Neither he nor other political leaders considered them revolutionaries either before or after the Revolution.

Che Guevara had left it written forever in his little Marxist manual Socialism and Man in Cuba: “The guilt of many of our intellectuals and artists resides in their original sin: they are not authentically revolutionary. We can try to graft the elm tree so that it will produce pears, but at the same time we must plant pear trees.”

But the pears that Che mentioned had nothing to do with human beings because an intellectual, writer or artist is characterized by his sensitivity, his pride, his sincerity. In general, they are solitary and proud.

But also they are, and that is their misfortune, an easy nut to crack, above all for a dictator with good spurs.

During those almost first three years of the Revolution, the most convulsive of the Castro regime — the number of those shot increased and the few jails were stuffed with more than 10,000 political prisoners — surely writers did not fail to observe how Fidel Castro was cracking the free press when after December 27, 1959, he gave the order to introduce the first “post-scripts” at the bottom of articles adverse to his government, supposedly written by the graphics workers.

It was evident that Fidel Castro, who controlled the whole country, did not want to approach them to fill leadership positions of cultural institutions founded by the regime, like the Institute of Art and Cinematographic Industry, House of the Americas, the Latin News Press Agency and numerous newspapers, magazines, and radio and television stations that were nationalized.

For minister of education he preferred Armando Hart. For the House of the Americas, a woman very far from being an intellectual, Haydee Santamaria. For the Cuban Institute of Radio and Television, Papito Serguera, and for the Naitonal Council of Culture, Vicentina Antuna and Edith Garcia Buchaca, two women unknown in cultural domain.

The first approach that Fidel Castro had with writers, June 16, 1961, in the National Library of Havana, could not have been worse. It was there where he exclaimed his famous remark, “Within the Revolution, everything; outside the Revolution, nothing,” and where he made clear that those who were dedicated to Art had to submit themselves to the will of the Revolution, something that is still in force.

The maximum leader left that closed-door meeting more than pleased on seeing the expressions of surprise and fear of many of those present, and above all by the words of Virgilio Pinera, one of the most important intellectuals of the 20th century when he said: “I just know that I am scared, very scared.” That precisely was what the new Cuban leader most needed to hear from the intellectual throng: Fear, to be able to govern at his whim.

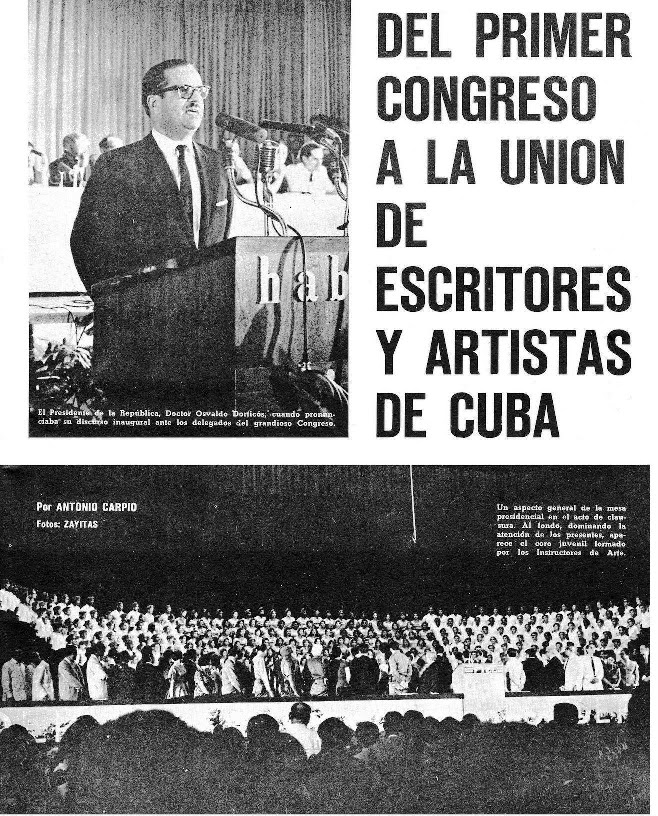

Two months later the Fist Congress of Cuban Writers and Artists was held, and UNEAC was founded. The intellectuals had fallen into line.

If something was said about that palatial headquarters, property of a Cuban emigrant, it is that the Commandant was allergic to all who had their own judgment, and for that reason he would never visit it, as it happened.

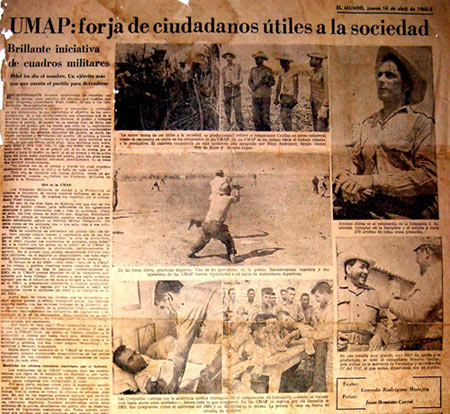

It is remembered still today that in a public speech on March 13, 1966, he attacked the homosexuals of UNEAC, threatening to send them to work agriculture in the concentration camps of Camaguey province. The “Enlightened One,” as today the president of UNEAC Miguel Barnet calls the Cuban dictator, kept his word. Numerous writers and graphic artists found themselves punished with forced labor in the unforgettable Military Units to Assist Production — UMAP.

These Nazi-style units were created in 1964 and closed four years later after persistent international complaints. If anyone knew and knows still the most hidden thoughts of the intellectuals, besides their sexual intimacy, it is the Enlightened One, thanks to his army of spies, members of the political police who work in the shadows of the mansion of 17th and H, in the Havana’s Vedado where UNEAC put down roots.

In 1977, one cannot forget the most cruel and abominable blow that the Enlightened One directed against the writers of UNEAC when his army of political police extracted from the drawers of the headquarters the files of more than 100 members — among them was mine as founder — so that they were definitively and without any explanation separated from the Literature Section of that institution.

Cubanet, April 11, 2014

Translated by mlk.