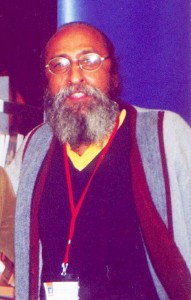

Angel Santiesteban Prats dedicates this article to Guillermo Vidal, to remember the tenth anniversary of his death. He wrote it from the Lawton Prison Settlement for the column “Some Write” from the digital magazine “OtroLunes” (“Another Monday”).

By Angel Santiesteban Prats

It’s always a pleasure to remember Guillermo Vidal.

It’s always a pleasure to remember Guillermo Vidal.

Sharing with him the adventure of writing has been one of the great rewards that life has offered me. His sympathy, modesty and talent seasoned his conversations. He was a man called to make friends, easy to like, and always persecuted by injustice, since they never could make him bow down. He maintained his literature at a high price, because he didn’t yield even one iota of his level of social criticism.

When they expelled him as a professor from the university, they didn’t even ask how he was going to live or maintain his family. Being despised and marginalized by the government of his territory in Las Tunas, by the demand of the political police, he became himself.

He was part of an intellectual existence that he accepted with stoicism, without complaint, which he endured in solitude and repaid with brilliant writing. That was his revenge.

After treating him like the plague for many years, the government offered a tribute to an official writer, and we agreed to attend if Guille would be among those invited. Once there, in the seat of the Provincial Party, in the same lair as the dictatorship, one of us said publicly that our presence had no other end but to lionize Guillermo Vidal, the most important living writer of Las Tunas, and one of the most important in the country; that it was a way of supporting him and demonstrating our friendship.

The government functionaries and those in charge of culture opened their eyes, surprised by the audacity. Those were the times when we still had not gained some rights that we have now, and where for much less than what is done today, there were immediate reprisals.

What is certain is that on that night and in the following days, we felt like better people and better intellectuals for showing our solidarity with him. Later he let us know that, from that moment, things got better for him. He stopped being banned and persecuted, because the authorities feared his contacts in the country, especially in Havana.

Now that we are on the eve of another congress of UNEAC (National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba), I remember what happened during the decade of the ’90s. After the vote to name the officers, Professor Ana Cairo, the officer of the Roger Avila Association of Writers, and I counted the votes, and there were a surprising number of artists who voted for Guillermo Vidal.

No one else had as many votes; no one even came close. However, later, when I saw who they elected, I understood that the votes were only a game, because Abel Prieto determined the election. They didn’t give any commission to Guillermo Vidal, not even in his own province. He was cursed, on the list of the marginalized.

When he died, it caused an infinite sadness, impossible to describe. I called the Institute of the Book (ICL), since I knew that they would have transport to take writers who wanted to participate in his burial.

The Taliban Iroel Sanchez, at that time the President of this institution, assured me that the microbus already had seats assigned. Of course, he was lying to me, and I intuited that in his words. Later, those who made the trip in that transport told me that not all the seats were taken.

I regretted very much not being able to say goodbye to him in that last moment. They feared that the truth would come out: that they had condemned him in life by closing all the doors to him that he knew his literature, a stroke of talent, would win. Surely I would have said that.

You can’t talk about Cuban literature at the end of the 20th century without mentioning the genres of the short story and the novel. However, in spite of the human misery that surrounded him, and the material poverty they obliged him to suffer, his genius at being a good Cuban jokester is the first thing that comes to mind when we think about him. That’s how I want to remember him now.

The book fairs in Havana take place in February and almost always coincide with his birthday, the 10th, that all his friends celebrated in harmony. We also celebrated February 14. I have one of his books, presented to me during those days, and I remember the dedication to me that “in spite of it being the day of love (Valentine’s Day), don’t get me wrong, I was a macho, macho guajiro.”

He had a spectacular snore. It almost loosened the nails from the beams and raised the roof. When you approached his room, the first sensation was that there was a roaring lion inside. The result? No one wanted to share a room with him.

Once, late in the night in Ciego de Avila, I met another writer from Las Tunas, Carlos Esquivel, literally crying in the lobby of the hotel because he couldn’t manage to sleep with those snorts.

When I described this scene the next day to Guillermo, he laughed like a naughty child. He asked me to repeat the story so he could continue to amuse himself, and he called for the others to listen to what suffering he was capable of inflicting, unconsciously.

In one of the prizes he won, and there were several, he had the luck to receive dollars. Then we got a telephone call saying that he was a relative of Rockefeller, and that he was ready to share his fortune; thus, he was generous. Certainly, in those few months I didn’t have a cent, and he continued in his material poverty. No one except his friends and spouse could believe him.

At one book fair in Guadalajara he told me that sometimes he had the impression that the government permitted him to leave to see if he stayed and they would get rid of him, and he laughed imagining the faces of the functionaries when they saw him return.

In one of his visits to Havana, he confessed to me how surprised he was because another writer told him that he envied him, and he couldn’t conceive of being anyone to envy, and he laughed. “When I go home from the university, at high noon, the cars pass me and no one gives me a ride, and they leave me wrapped in dust to the point that I stop breathing so I don’t swallow the dust,” he said, and he began to laugh.

Then I told him that I would exchange all that poverty for his books, that I also envied him, and he got serious, and in a respectful tone asked me if I was serious.

Thus he always comes into my memory, ironic as the priest’s pardon after confessing sins, and as sweet as the tamarind that they give the leaders to taste.

This year is the tenth anniversary of his physical disappearance. And every year, in spite of some mediocre political and cultural figures who agree to forget him, the imprint of Guillermo Vidal on Cuban culture overrides frontiers and political regimes. And this is elaborated with the passage of time, which was the only thing he didn’t laugh about. To struggle against time through writing was an exercise on which he bet his life.

Published in OtroLunes.

Please follow the link and sign the petition to have Amnesty International declare the Cuban dissident Angel Santiesteban a prisoner of conscience.

Translated by Regina Anavy

9 April 2014