![]() 14ymedio, Havana, Reinaldo Escobar, 30 July 2016 — Ten years after the Proclamation in which Fidel Castro announced his departure from power, that document continues to reveal distinctive features of a personality marked by the desire to control everything. More than an ideological legacy, the text is a simple list of instructions and it is unlikely that the official media—so addicted to the upcoming major anniversary of Fidel Castro’s 90th birthday—will offer an assessment of whether these instructions have been followed.

14ymedio, Havana, Reinaldo Escobar, 30 July 2016 — Ten years after the Proclamation in which Fidel Castro announced his departure from power, that document continues to reveal distinctive features of a personality marked by the desire to control everything. More than an ideological legacy, the text is a simple list of instructions and it is unlikely that the official media—so addicted to the upcoming major anniversary of Fidel Castro’s 90th birthday—will offer an assessment of whether these instructions have been followed.

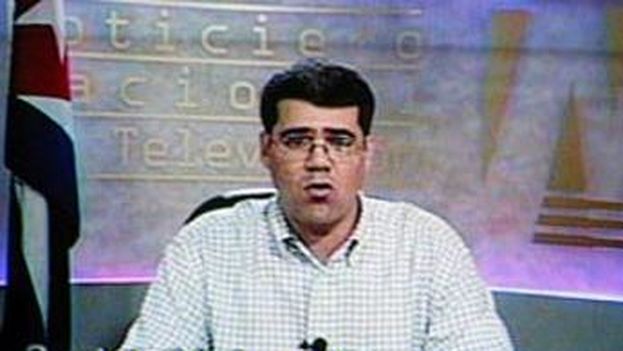

On 31 July 2006, the primetime news broadcast brought an enormous surprise. Around nine at night Carlos Valenciaga, a member of the Council of State, appeared in front of the cameras to read the Proclamation of the Commander in Chief to the People of Cuba, where he announced that due to health problems he felt obliged “to rest for several weeks, away from my responsibilities and tasks.”

After giving his version of the complications that plagued him and the causes that had caused them, Fidel Castro offered six basic points in this document and additionally left instructions about holding the Non-aligned Summit and about the postponement of the celebrations for his 90th birthday.

The first three points of the proclamation are dedicated to the transfer of powers to his brother Raul Castro as head of the Party, the government and the armed forces. The order for these transfers were completely unnecessary because it was already in his position to undertake these functions given that he was then in second position in both the hierarchical order of the Party and the government. It is striking that in each case he reiterated the “temporary delegation” of the transfer of responsibilities.

In the three remaining points he delegated (also on a temporary basis) his functions “as principal promoter of the National and International Public Health Program” to then Minister of Public health Jose Ramon Balaguer; the “principal promoters of the National and International Education Program” to Politburo members José Ramón Machado Ventura and Esteban Lazo Hernández; and as “main promoter of the National Energy Revolution in Cuba and collaborator with other countries in this area” Carlos Lage Davila, who was then secretary to the Executive Committee of the Council of Ministers.

In a separate paragraph he clarified that the funds for these three programs should continue to be managed and prioritized “as I have personally been doing” by Carlos Lage, Francisco Soberon, then minister-president of the Central Bank of Cuba, and Felipe Perez Roque, at that time minister of Foreign Relations.

Almost immediately after having read that proclamation there was an enormous military mobilization in the entire country, called Operation Caguairán. Shortly afterwards the former omnipresence of the Maximum Leader was reduced to some sporadic Reflections of the Commander in Chief published in all the newspapers and read on all the news shows. Twenty months later the National Assembly formally elected Raul Castro as the president of the Councils of State and of Ministers and later the 2011 Sixth Congress of the Communist Party elected him as First Secretary.

From his sickbed Fidel Castro affirmed on that 31st July that he did not harbor “the slightest doubt that our people and our Revolution will struggle until the last drop of blood to defend these and other ideas and measures that are necessary to safeguard our historic process.” In the text itself he asked the Party Central Committee and the National Assembly of Peoples Power “to strongly support this proclamation” although in previous lines he had had already dictated that the party “supported by the mass organizations and all the people, has the mission of assuming the task set forward in this Proclamation.”

A decade passed, the temporary absence of the “main driver” became permanent and four of the seven men named no longer occupied their positions. The reader of the proclamation was ousted. The programs mentioned have become part of the normal functions of the ministries in charge of these tasks and the “corresponding funds” (although no one has proclaimed it officially) are no accounted for in the nation’s budget.

While the 80th birthday wasn’t able to be held with his presence, nor the 2 December 2006 50th anniversary of the landing of the Granma, the yacht that brought the Castros and other revolutionaries from Mexico, as foreseen in his proclamation, now in 2016 all cultural events, sporting events, productive activities, have been dedicated to his 90th birthday.

The ultimate significance of that proclamation lies not in the message it contains, among other things because its author seemed to be persuaded that this was not his political testament but a “bear with me, I’ll be back in a while.”

The final results of this proclamation has been like a blinding spotlight that goes out, a permanent noise that we have become accustomed to and suddenly stops ringing, a will that ceases to give orders, the termination of an omnipresence. The absence occasioned has more connotations of relief than of a capsizing. There is nostalgia. The anxiety about the final outcome has been diluted in a fastidious tedium, like that of sitting in front of those films that stretch unnecessarily.