Ivan Garcia, 16 December 2015 — Laying the blame on “Yankee imperialism” or the “perverse and criminal” Cuban Adjustment Act will not stem the flow of people escaping poverty and bleak futures.

The national debate should be of a different nature. A responsible and reasonable government would ask itself what went wrong. Seeing Cuban migrants within the broader context of third-world emigration would amount to de facto recognition that the island’s vaunted economic and social model had failed.

Ask a Mexican or a Syrian fleeing the civil war if he approves of the government of Enrique Peña Nieto or Bashar al-Assad.

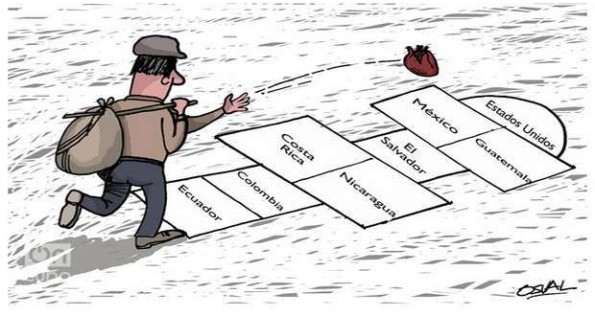

People emigrate to other countries for a life with dignity, a better salary or the opportunity for professional development. The Cubans who are leaving now are trying to change their circumstances.

I spoke with dozens of Cuban citizens stranded in Costa Rica after the decision by Nicaragua’s president, Daniel Ortega, to close the border at Peñas Blancas.

Not one was a political dissident or felt persecuted by the government. But they will tell you quite frankly that they are tired. Tired of everything. Tired of the aged and ineffective Castro government. In spite of guaranteed universal health care and a highly politicized public education, they are tired of their dull gray lives, the social controls, the rationing and the question mark hanging over their futures. And they have lost faith in those running the country.

Most of the more than four thousand migrants in Costa Rica want to be free men and women, to be themselves and not someone else’s tool.

It is a heterogeneous and diverse group. Most are professionals or technical workers who in Cuba had to put away their college degrees and take up burning pirated discs, driving taxis or selling mass-produced junk.

Of course, there are also the low-lifes — prostitutes, drug dealers and deadbeats — as in any human group, but they are in the minority. Their political leanings are not comparable to those of their compatriots, who were outcast by decree and whose property was seized.

But they should not be looked down upon because they are not dissidents or because they silently go along with the Castros’ edicts. Cubans do not have what it takes to be martyrs. Autocratic regimes are very efficient at devising systems of social control. That is a fact.

There is no country in which a communist regime been overthrown through mass uprising. The Berlin Wall came down because East Germans wanted to get out. The only large-scale protest to take place in Havana was in 1994 and at issue was the desire to emigrate.

In societies with tyrannical policies towards opponents such as Cuba, North Korea and Vietnam — societies in which a market economy serves as an escape valve, providing some degree of prosperity — it is unlikely that regime change will come about through popular revolt.

The option for Cubans who cannot afford milk in their morning coffee is to leave the country by any means and at any price. And preferably via Miami. But even in Ecuador or Spain, where there is no Adjustment Act, there are tens of thousands of Cuban residents.

Emigration in Cuba has political overtones. Even before the Cuban Adjustment Act took effect, Fidel Castro was branding any Cubans who wanted to leave the country as “worms.” They were demonized by the system.

They were fired from their jobs and, while waiting for an exit visa, had to work on collective farms. When they left, they were stripped of their property.

Setting sail on a raft from the island’s coastline was a crime punishable by up to eight years in prison. After being tried, an irritable Fidel Castro would insult them, calling them “scum.”

In 1980 the regime introduced the infamous acts of repudiation — fascist-inspired verbal and physical public assaults — against those planning to emigrate. Before going overseas, emigres were forced to leave behind their jewelry and other personal possessions.

As Hitler similarly did to the Jews, they were marked by a scarlet letter. Such practices were later abandoned but there was never a public apology made to those who had been humiliated.

The new strategy represents an accommodation to new political circumstances and the urgent need of an unproductive state economy to bring in dollars to sustain itself.

It is an economy in which the “worms” now provide remittances, replenish telephone accounts, travel to Cuba and send packages. Their contributions constitute the island’s largest industry after the export of medical services.

The Adjustment Act is a pretext, not the real cause of Cuba’s madness. In any case, it is a problem for the United States, which should either revise it or strictly apply its provisions.

Responsibility for the current out-of-control migration rests with the country’s military dictatorship. Before 1959 Cuba was a country of immigrants. Between 1910 and 1925 the island took in one-third of all Spanish immigrants to the Americas. In 1902 it absorbed 11,986 immigrants and it 1920 the figure grew to 174,221.

Some 9,571 Cubans emigrated to the United States between 1931 and 1940; 26,313 emigrated between 1941 and 1950; 208,536 emigrated between 1961 and 1970. According to U.S. census figures there were 1,213,418 Cubans living in Florida, an increase of 45.6% over the year 2000 census figures.

According to U.S. Customs Service statistics for the current fiscal year, more than 45,000 Cubans have entered the country by crossing the Mexican and Canadian borders, and even the Russian border with Alaska.

In spite of the 2013 emigration reforms, Cubans who leave the country must pay extremely high fees to renew their passports. And they lose their properties if they reside for twenty-four months outside the country.

Furthermore, the government does not recognize dual citizenship, so overseas Cubans must request permission to visit their homeland. And they have no political or social rights when they are living outside of Cuba.

The Cuban government maintains its own version of the Adjustment Act, directed at Cubans living overseas, because that is the way Fidel Castro wanted it.

Ivan Garcia

Hispano Post, December 7, 2015