Act I: The Barricade

I notice the foul stench the moment I turn the corner and see the piles of garbage blocking the street. A pair of patrols is stationed, threateningly, half a block away. I keep walking as though it has nothing to do with me but a State Security agent — dressed in civilian clothing and without identification, as per usual — stops me and I realize that it is, indeed, about me.

“Good afternoon, where are you headed?” he challenges me.

“To a friend’s house,” I reply, allowing myself this small amusement.

“But… to whose house?” asks a second agent, approaching inquisitively and also dressed as a civilian, of course.

I cut to the chase and look him in the eye. “Yes, I’m going to [Antonio] Rodiles’ house.”

“Let me see some identification,” he demands, as though issuing an order. The radio transmits my information and immediately the agent returns, this time with an unequivocal command. “You cannot pass!”

“Yes, I need to get by,” I reply.

“No, you cannot,” he shoots back.

“Then let’s see what you do about it because I need to pass,” I say self-righteously.

Because of my “insolence,” I am subjected to a thorough search for a cellphone I do not have.

“Frisk him and take him away!” he finally orders. It is 4:20 PM.

Act II: The Detention

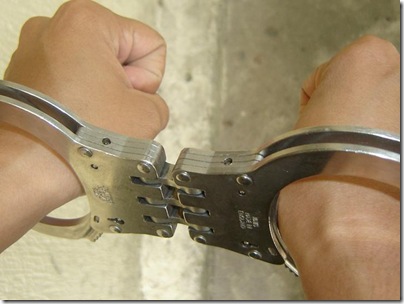

I try telling the agents of the National Revolutionary Police (PNR) that the handcuffs are not necessary, but they clamp them on tightly. In a few minutes I am at the Territorial Unit of Criminal Operations and Investigations (DIVICO 3) located on 62nd Street at 7th and 9th in Playa, where I am met along the side of the parking lot.

They take off the handcuffs but their imprint — on the skin, that is — will last for hours. The booking officer asks for my name and the group to which I belong. I identify myself and I say that I do not belong to any group. There is no point in telling him I am a doctor, who would have been at Rodiles’ house for only 20 minutes because the next day I am on call at the hospital for 24 hours and must now get home. Moments later another agent appears and asks, “Haven’t you had problems with your work… or something like that?”

“Yes, that’s me,” I say, almost interrupting to save him from further reflection. Having verified my coordinates, he leaves. That is when the man I presume to be the boss relaxes his tone of voice a bit. I tell them they are making a serious mistake, that it will lead to nothing, that they have no right to detain me, that they should try other methods.

“So, tell me,” asks the official, “how would you solve this?”

I tell him it was not up to me to solve the problem. He spends the next hour trying to persuade me to go home but I insist that first I have to go to Rodiles’ house.

“You can go there some other time but not today,” he tells me emphatically. “If you try to do it again, we’ll just arrest you again. We’ll be at this all day, so let’s just avoid the hassle.”

During this “impasse” I manage to talk for a few minutes with Gorki Avila, who is in great pain after his “peaceful” arrest. The agents come back, convinced the game is deadlocked. They confiscate my camera and send me to a jail cell.

Act III: Convicted

It is an almost hermetic cell of about 50 square meters and about 6 meters high that, in addition to a door, has a single barred window half a meter tall and about 5 meters from the floor. Three granite benches are the only elements besides the walls, which are painted with several layers of quicklime in an attempt to cover up the graffiti of slogans and curses that bear witness to the cell’s history. Inside are thirteen detainees whose luck today has been similar to mine. They tell me that before they arrived there were others who passed through and estimate that — in this one unit — there may have been fifty prisoners, including several women.

Act IV: The Wait

In time boredom and heat set in, forcing me to remove my pullover. The hours pass in fleeting conversation with occasional outbursts from those screaming at the top of their lungs at the sons of bitches. At the end of the afternoon they bring in Gorki, who is still in pain and complains repeatedly of a headache. After awhile we manage to get him medicated at a nearby clinic and he returns, his pain eased.

About 8:00 PM hunger sets in. Those who so desire are taken to eat but I decline. I guess captivity has taken away my appetite. It is at this moment that the official I saw earlier that afternoon chooses to diffuse the tension— he says to call him Mandy — by playing the good cop. In a tone that in other circumstances might be described as conciliatory, we chat and even philosophize a bit. I take the opportunity to reiterate, for the third time, that I need to call home and, also for the third time, that I am running out of time.

Just then it occurs to me that not only am I being arbitrarily detained but that I am what would technically be described as a missing person. My family will have been waiting for me for several hours without knowing of my whereabouts. For a long time the cell door has remained open, giving the impression that we could leave our confinement and go have a cup of coffee at the corner, if only we were dumb enough to believe it.

The hours pass and little by little the detainees are released so that by 10 PM only five of us remain. Around 10:30 PM they call out for Edilio, an attorney with the Cuban Legal Association, along with another detainee. Now there is only Gorki, Aldo (who manages the Castor Jabao website*) and I. Around 11:00 PM three mats appear and it is then that I resign myself to spending the night in jail.

Act V: “Liberated”

In the morning the bars finally open and they call out my name. I say goodbye to Gorki and Aldo, who would remain there 12 hours more. At the exit a PNR official shows me a document. In the place where I am supposed to sign, someone has already written, “Did not sign,” which saved me the trouble since that was exactly what I was thinking anyway. The document mentions something about counter-revolution but I tell them they should look for counter-revolutionaries among the crooks who are embezzling this country. They give me back my camera but not before completely draining the battery

After the Terminal Lido stop the bus takes me towards Artemisa. I am gross. I quickly bathe, have something for lunch and head back to Havana for my shift at the hospital because, in spite of it all, it is not the members of my team nor my patients who are responsible for my detention.

Last Act: The Next Day’s Pill

My shift is a killer. When I get home that evening, I open the newspaper Granma to find that in a farewell address at Nelson Mandela’s memorial service, President Raul Castro spoke movingly of the need for the people of Latin America to be “respectful of diversity, with the conviction that dialogue and cooperation are the way to resolve differences and civilized coexistence of those who think differently…”

I do not find out about this until the next day for reasons that are obvious. As the president of this country, who now chairs the United Nations Human Rights Council, is delivering his speech, this Cuban was being detained for 16 hours for trying to attend a State of Sats meeting. This amounted to a violation of his right to freedom of movement, freedom of assembly and freedom of thought, considering he was only thinking of going to this meeting.

The question one then has to ask is, What is the Cuban government afraid of? Could it be that the it has not ratified the UN Convention on Civil and Political Rights or the Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which it signed in 2008, because it intends to continue its attacks on our civil liberties. This is precisely why, now seven weeks later, I am providing an account of these events. In light of the evidence, further comments are unnecessary.

*Translator’s note: a satirical Cuban website.

29 January 2014