HAVANA, Cuba, December 2013, www.cubanet.org – The poverty in which most Cubans live — and to which they adapt, thanks to the meticulous mechanisms of power that 54 years of State terror have imposed — is not an insurmountable fate. It would be enough for the Cuban government to respect all human rights, opening the political and economic game, in order to improve the living conditions of the island’s inhabitants.

HAVANA, Cuba, December 2013, www.cubanet.org – The poverty in which most Cubans live — and to which they adapt, thanks to the meticulous mechanisms of power that 54 years of State terror have imposed — is not an insurmountable fate. It would be enough for the Cuban government to respect all human rights, opening the political and economic game, in order to improve the living conditions of the island’s inhabitants.

Misery is aggravated when one has neither a place to live nor economic resources to rent, build or buy a house. It is estimated that, in the Central Havana municipality alone, 6,201 families (24,584 people) are affected by the uninhabitable condition of their dwellings. Of that number, only 125 families are located in the so-called transit communities: collective shelters, as they are known in Cuba.

But those figures do not shed light on what it means for a family to live sheltered. One must cross the threshold of figures in order to see up close the true face of the tragedy.

The “Collective Shelter” of San Rafael 417 in Central Havana

The “Collective Shelter” of San Rafael 417 in Central Havana

According to those who live there, the building previously housed a factory for sanitary napkins (intimates in the Cuban language). Decrepit posters with some communist slogans are not missing. The hall is divided into different rooms where the belongings of those who have come to stop in this site are grouped. What seems to be the bathroom is in fact a latrine. Nor is there seen anywhere a sink with running water.

Iverlysse Junco is 29 years old. The door of the little room of wooden planks where she lives with her husband and four children creates a false illusion of privacy. Everything looks poor and ugly, but it is impressive to see the white of the diapers that cover the cradle of her baby born a month ago. She has not neglected her personal appearance in spite of the fact that she is not expecting anyone; she keeps her dignity in the cleanliness and order that she maintains in the 4 x 4 meters where they live.

Six years ago they left a tenement in danger of collapse. The room has not a single window. The first thing that she shows us behind a curtain is another sliding wooden plank that gives onto the street.

Six years ago they left a tenement in danger of collapse. The room has not a single window. The first thing that she shows us behind a curtain is another sliding wooden plank that gives onto the street.

“When we came it was completely closed, but one day I could not endure any longer the lack of air and I grabbed a saw in order to make that opening,” she says. “The bad thing is that now my husband and I cannot leave together, because one of us two has to stay in order to make sure no one enters and takes our things. They came to assess a fine against me, for nothing less than for altering the facade. But I told the district delegate that they are very familiar with my situation.”

On an improvised kitchen counter is a pair of electric burners where she does everything: from cooking to boiling the diapers, as is customary among Cuban mothers who have no way to pay for the luxury of disposable diapers, which involves a greater cost than a month’s salary.

The baby is cold as a consequence of the humidity: she has to hang out clothes there inside. The water she asks of a neighbor on the block. He lets them fill the buckets that they then carry to a little tank in the corner of the room. That limited water has to serve them for washing, mopping, cooking and bathing in the same room. Part of everyone’s routine every day is to keep the deposit full. But with other needs there is no arrangement; they have to urinate and defecate in a bucket dedicated to that purpose and then go out to pour it down the drain in the street.

The baby is cold as a consequence of the humidity: she has to hang out clothes there inside. The water she asks of a neighbor on the block. He lets them fill the buckets that they then carry to a little tank in the corner of the room. That limited water has to serve them for washing, mopping, cooking and bathing in the same room. Part of everyone’s routine every day is to keep the deposit full. But with other needs there is no arrangement; they have to urinate and defecate in a bucket dedicated to that purpose and then go out to pour it down the drain in the street.

“Everything is hard here. The most difficult is getting up in the morning and having to be watching the people to be able to go out to dispose of the bucket. I cannot not have the bleach for cleaning and the freshener.”

Her husband works in demolition, which is why she is aware of the quantity of collapses that occurs, especially when it rains.

“When do I leave here? The collapses are going to continue because Havana is falling down.”

Although Iverlysse and her husband work a lot, they see themselves reduced to total dependency on the State. In a collectivist system, which condemns private property and the free market, the hypothetical solution is that, not with one’s own effort, but with collective work, the Junco family will get a house in which to live.

In practice, society has submitted to state control and planning. The happiness of the Junco family depends then on their file being privileged in the eyes of the official, who next December 20 will have to decide if, among the 900 cases that are presented in the whole of the Havana province — after prioritizing the “cases” that have spent 20 years sheltered, hoping — theirs qualifies as sufficiently affected by an extreme situation.

In practice, society has submitted to state control and planning. The happiness of the Junco family depends then on their file being privileged in the eyes of the official, who next December 20 will have to decide if, among the 900 cases that are presented in the whole of the Havana province — after prioritizing the “cases” that have spent 20 years sheltered, hoping — theirs qualifies as sufficiently affected by an extreme situation.

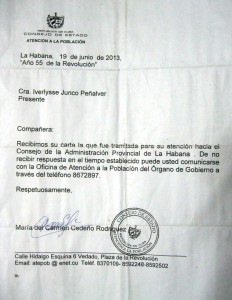

“I have already gone to the Province (Office of Dwellings) and to the government. Three times I went to Revolution Plaza and seven times I wrote letters to the State Counsel. On all those occasions the answer was: You have to wait. There are worse cases than yours. What can be worse than this?” Iverlysse asks herself.

The statistics about the numbers of sheltered people and those waiting to become sheltered, were offered by the Municipal Unit of Attention to the Transit Communities (UMACT) of the Central Havana municipality by a person who requested anonymity. The number of the 900 cases that will be presented next December 20 was provided by a housing worker who also wanted to withhold his name.

December 15, 2013/ By Lilianne Ruiz.

From Cubanet

Translated by mlk.