Dimas Castellanos, 22 January 2018 — The reform measures implemented in Cuba in 2008 failed: voluntarism, statism, centralized planning, and subordination to policy and ideology dashed them. The coexistence of two currencies confirms this.

In 2011 monetary unification formed part of the Guidelines approved at the Communist Party’s 6th Congress. In 2013 a timeline was announced to implement it, and there was talk of a prompt solution. In 2016 its elimination was said to be urgent.

In 2017 buying with Cuban pesos was authorized for use at retail establishments, and bills of 200, 500 and 1,000 pesos were placed in circulation to facilitate transactions. Then, in December, President Raul Castro stated: “the elimination of the dual currency system constitutes the most pivotal process to make progress on the updating of our economic model. Without solving this, it will be difficult to advance correctly.” He concluded by saying: “I must recognize that this issue has taken us too long, and its solution cannot be put off any longer.” (Granma, 22 December 2017)

In this article I limit myself to the historical background of the dual currency system; that is, its past and present.

Dual currency in Cuba before 1959

In the period between 1878 and 1895 two key events took place.

First: the explosion of the sugar industry and the export of more of 90% of Cuban sugar to the U.S.A. allowed the American Government to impose the Bill McKinley agreement on Spain, a commercial reciprocity treaty that allowed the free flow of Cuban raw materials to the American market, including sugar, which accounted for 94 of every 100 pesos the island took in.

The second: the important role of American investments in the structures of agrarian holdings, sugar plants, and mining facilities.

Both developments, after Spanish domination, facilitated the introduction of the dollar into Cuba as a monetary resource.

The Spanish centén and the French luis continued to circulate in Cuba until 1914, but official payments were made according to the exchange rate established by the dollar. In order to diminish dependency on it, in October of that year the Government of General Mario García Menocal created the National Monetary System, whose first measure was the “Economic Defense Law,” which gave rise to a national currency based on the gold standard, with the same weight and law as the American dollar.

Although it arose subordinated to the dollar, which was legal tender, after the Economic Defense Law the peso began to prevail.

In 1924 86% of the currency in circulation consisted of dollars. In 1934 an acute depreciation made it necessary to devalue the peso, which continued to function as a measurement of value, but the means of circulation was assumed by the peso de plata (silver peso) and certificados de plata (silver certificates), legal tender as of 1935.

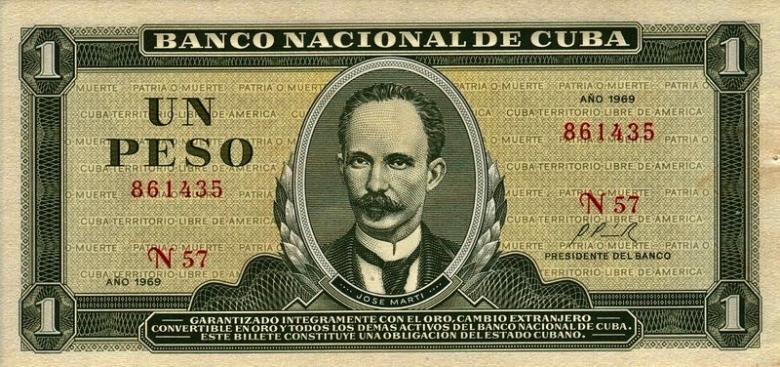

In 1939 the Currency Destabilization Fund was founded, and in 1948 the National Bank of Cuba was created, which replaced the peso de plata with notes from the National Bank, obligatory and unlimited legal tender.

In The Monetary Unification of 1914 Elías Amor sums up the results with just a few words: “The introduction of the National Monetary System created a reliable, modern and well-built system that allowed the national currency to become a store of value, on the basis of which commercial and financial transactions and operations ensued that made possible a remarkable dynamism and growth of the economy under the Republic.”

Dual currency in today’s Cuba

The revolutionaries who rose to power in 1959, imbued with high doses of subjectivism, and believing themselves to be immune from the laws that govern economic and financial phenomena, moved to eradicate mercantile relationships and money. They nationalized the national and foreign banks, and placed these responsibilities in the hands of “loyal” people.

An example was the case of the economist Felipe Pazos Roque – founder and first president of the National Bank of Cuba, in 1948 – who, opposed to the coup d’etat of 1952, resigned his post. Pazos, who participated in the civic struggle against the Government of Fulgencio Batista, in 1959 was again assigned this responsibility, but his ideas were found not to be “loyal.” Months later he was replaced by Commander Ernesto Guevara.

Eighty years after the advent of the Cuban peso, with a deficient economy, but buoyed by Soviet subsidies, extended for ideological and geopolitical reasons, and as socialism was crumbling in Eastern Europe, Cuba was in the throes of a severe crisis, dubbed with the euphemism “Special Period During Peacetime,” during which, between 1990 and 1994, the country’s GDP contracted 34.8%.

The Government limited itself to implementing measures to subsist, but without really changing. After 35 years of revolution and confrontation with the U.S.A., it decided to introduce, for the second time in the history of Cuba, the enemy’s currency.

To erase the negative image of the greenback, the CUC was created, a convertible peso assigned a value similar to that of the dollar, but without its attendant backing. A 10% tax was placed on the dollar, the CUC appreciated in relation to it by 8%, and ultimately achieved a one-to-one value, but the 10% tax on the dollar was maintained. In summary, Cuba features the peculiarity of having two currencies, neither of which is based on gold or on the GDP to be truly convertible.

The monetary duality exacerbated social differences and accelerated the loss of the Cuban peso’s already scant value. Its effect was evident in the inflation of prices in the black market, and meager wages and pensions. It frustrated production, reduced productivity, and lost or diminished its functions as a value of measurement and instrument for the acquisition of goods, savings, settling debts and making payments.

Monetary unification stands, along with the restitution of citizens’ liberties, as an inescapable necessity, one that cannot be put off, despite challenging conditions, particularly because the entity that must enact this unification, the Government, is the same that introduced the dual system, and until now has not demonstrated the political will necessary to carry out a critical analysis of itself and implement the only possible solution. The fact is that 60 years in power make it responsible for both the good and the bad.

The Cuban peso lacks support for the payment of goods and services sufficient to recover its functions and for it to be comparable to other international currencies. Monetary unification, by itself, will not solve the crisis. The solution calls for efficiency and an increase in production, which is impossible without major investments. Foreign because the monetary duality is an obstacle; national because the power refuses it.

A project is pressing, headed by this Government or that which replaces it, that features the decentralization of the economy, restitutes citizens’ rights and liberties, allows for the development of a middle-class, and removes the obstacles that restrain production and productivity. But none of this is possible under statization and a planned economy subordinated to the interests of those in power.

Note: Translation from DiariodeCuba.com