With the unexpected death of Eusebio da Silva Ferreira on the morning of January 5, the soccer world lost one of its greatest players and an extraordinary ambassador for the sport, an honest and simple man, who never forgot his humble origins despite his fame.

With the unexpected death of Eusebio da Silva Ferreira on the morning of January 5, the soccer world lost one of its greatest players and an extraordinary ambassador for the sport, an honest and simple man, who never forgot his humble origins despite his fame.

Sports columns of the five continents have dedicated reviews and reports to him. Photos and videos have flooded the internet. Hundreds of condolences have made their way to his widow, Flora, and to his children and grandchildren. And millions of messages have circulated on social media sites remembering The Black Panther, as he was known, for his speed and skill.

Eusebio was born in the suburb of Mafalala, in the city of Lourenço Marques, now Maputo, Mozambique. He was the fourth son of seven born to Mozambican Elisa Anissabeni with her husband, the Angolan Laurindo Antonio da Silva Ferreira, a railroad worker. His father died of tetanus when Eusebio was eight years old. He and his siblings were left in the charge of their mother, in a situation of extreme poverty. As a boy, Eusebio often escaped his classes to play barefoot soccer with his friends in improvised playing fields. continue reading

Carlos Toro dedicated an article to him in El Mundo: “On the 25th of January, he would have turned 72-years-old and Portugal would have rendered him, like it is doing today, high sports and patriotic honors. ’Wherever I go, Eusebio is the name that people mention to me,” Mario Soares, president of Portugal from 1986-1996, once said.

“Forget about Cristiano Ronaldo, the young mythical figure of Portuguese sport, and about Luis Figo, who has the greatest number of international attendance for his country. The king of Portuguese football was, is Eusebio da Silva Ferreira. Eusebio. The International Federation of History and Statistics considers him to be ninth among the 50 best players in the twentieth century.

“A mulato, the son of a white father and a black mother, born in Mozambique, won the right to be saluted as one of the best soccer players of all time, including those we have in the 21st century, thanks to his performances in the imposing Benfica and with the magnificent Portuguese national team of the 1960s”.

Pelé in his Twitter profile said: “I regret the death of my brother Eusebio. We became friends during the World Cup of 1966 in England and last met in the game between Brazil and Portugal in Boston (in September 2013). My condolences to his family and may God receive him with open arms”.

Jaime Rincón wrote in Marca: “Eusebio’s career was unique from the start. His arrival in Europe was full of the mystery and emotion that usually accompanies great figures. At 17 years old, Eusebio was smuggled through the airport of Maputo on course to Lisbon. There, Benfica hid him in a small hotel room in the Algarve under a false name. No precaution was too small to secure the soccer player and prevent his ending up in the Sporting Club of Portugal.*

“With a small salary given his sporting achievements until then, Eusebio soon demonstrated that soccer was seeing a different type of player. Capable of doing 100 meters in eleven seconds, the Panther had power and ability, speed and definition. He possessed a veritable cannon in his right leg, a lethal weapon that made all the difference.

“At only 18-years-old, Eusebio dazzled on the day of his debut in Paris. Before another great such as Pelé, the Panther left the field with 3-0 on the scoreboard. With an insulting audacity, the pearl of Mozambique achieved a hat-trick that not even the subsequent goals of The King could erase”.

Sir Bobby Charlton, a living legend of British football and ex-player for Manchester United and England, remembered him like this: “Eusebio was one of the best soccer players I have had the privilege to play. I met him on numerous occasions after our sports careers were finished. I’m proud to have had him as both an opponent and a friend”.

Eusebio never came to Cuba, but we Cubans who love football and sports knew him. And we thank him for having shot down prejudices and taboos. And for proving, in any country and in any sphere of life, whether you be man or woman, white, mulatto or black, young or old, what matters is dignity and the spirit of excellence.

Iván García and Tania Quintero

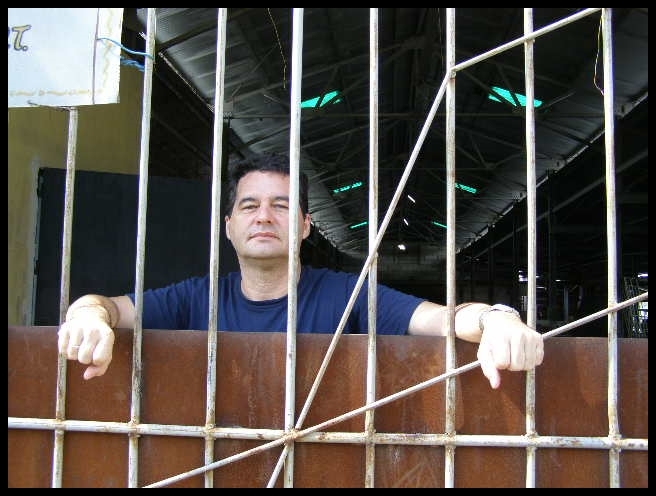

Photo: Eusebio da Silva Ferreira. Taken by The Guardian, from an interview on June 6th, 2010.

*Translator’s note: There was fear that he would be kidnapped by a rival team.

Translated by LW

6 January 2014