Ivan Garcia, 5 November 2016 — When I began writing in 1996 as an independent journalist for Cuba Press, Arnaldo Ramos Lauzurique was no longer working as an economist for Cuba’s Central Planning Agency (JUCEPLAN ) and had already become an opponent of the Castro regime.

In 1991, together with another economist, friend and colleague, Manuel Sánchez Herrero, he joined the Cuban Social-Democratic Party, directed by Vladimiro Roca Antúnez. Later, with Martha Beatriz Roque Cabello, also an economist, the three participated in the founding of the Institute of Independent Economists of Cuba.

The most well-known members of the Internal Dissidence Working Group were Martha Beatriz Roque Cabello, Vladimiro Roca Antúnez, René Gómez Manzano and Félix Bonne Carcassés, and among their closest and most loyal collaborators were Sánchez Herrero and Ramos Lauzurique. These two also contributed their bit to the drafting of La Patria es de Todos — The Fatherland Belongs to Everybody — the document with the greatest national and international reach drafted by an opposition group on the Island.

La Patria de Todos was launched in June 1997, and barely one month later, four principal members were violently arrested (Martha, Vladimiro, René and Félix). On March 1, 1999, in the Marianao Court, the trial took place, one of those big, repressive shows mounted by Fidel Castro and the Department of State Security. The trial took place two weeks after the one-note Parliament, presided over by Ricardo Alarcón, approved the Law of Protection of National Independence and the Economy of Cuba, better known as the Gag Law, which, if violated, provides for a penalty of 20 years or more in prison.

The four were given different punishments, although the only one who served the whole five years of his sentence was Vladimiro (they gave him a stiffer penalty for being the son of the Communist leader Blas Roca Calderío, the ex-Secetary General of the Popular Socialist Party). Quietly, in their own discreet way, Arnaldo and Manuel continued the best they could with their efforts for the Internal Dissidence Working Group.

In those days, Arnaldo was living with his two children and wife, Lydia Lima Valdés, in a one-story house near the old Cerro stadium. Cuba was going through a “Special Period,” and Arnaldo, in order to survive, was buying raw peanuts in an agromarket, roasting them and packing them into paper cones. He went on foot, selling them on the outskirts of the Zoo on Avenida 26 in Nuevo Vedado. Manuel already was in very poor health, with prostate cancer. in 1985, when he still worked at JUCEPLAN, he spent a year under arrest, accused of insulting authority. The motive? A book that Sánchez Herrero wrote about the similarities between Benito Mussolini and Fidel Castro.

But the two (and I know this through my mother, the journalist Tania Quintero, who was a good friend of Arnaldo and Manual), in addition to continuing unabated in their opposition to the regime, often got together to analyze the economic, political and social panorama of Cuba in the international context. “Some afternoons, in 1998, I had the privilege of conversing and debating for a long time with Arnaldo and Manuel. We met in the house of Elena, the daughter of Martha Beatriz, on calle Neptuno. There were tremendous shortages, but Elena always managed to offer us a snack and coffee. And more than once she didn’t let us leave before she had offered us a plate of peas she had just made and a slice of bread, which was then a luxury.”

For lack of money, Arnaldo walked around Havana on foot; his health was good. Manuel was taken away by cancer on May 15, 1999. Because their pockets were empty, Arnaldo and Tania couldn’t send a wreath, but they went to his very modest service, in the Zanja funeral home, the funeral home of the poor. They sat on chairs that allowed them to see the entrance of the funeral home and detect the presence of officials of the political police dressed in civilian clothing.

Tania told me, “We saw Odilia Collazo come in, supposedly a dissident who led a pro-human rights party. She and a woman who accompanied her approached the row where Arnaldo and I were sitting and greeted us. We responded coldly and when they sat down next to us, Arnaldo and I immediately got up and left.”

Manuel, as well as Arnaldo and Tania (and also Raúl Rivero) always suspected that Lili, as they called her, was a snitch. And they weren’t wrong: in April 2003, State Security itself uncovered her as an agent infiltrated into the ranks of the dissidence. Collazo managed to fool several diplomats — among them some at the U.S. Interests Section — and also Cubans in exile in Miami, while she offered her house for meetings with dissidents and then later reported them.

In 2002, Martha Beatriz organized one of the opposition groups that, in my opinion, was more focused on people and their reality: the Assembly to Promote Civil Society in Cuba. It was supported by Gómez Manzano, Bonne Carcassés and Arnaldo Ramos, who always was a kind of right hand for Martha, because he was a disciplined and organized person, with great skill in researching information and extreme care when it came to drafting statistical tables, reports or articles.

The Assembly had a short life. They gave it the coup de grâce on March 20, 2003, when they detained Martha Beatriz and some 20 dissidents in the capital and provinces who passed several days fasting, among them a young black man named Orlando Zapata Tamayo. Seven years later, on February 23, 2010, Zapata Tamayo would die as a result of a prolonged hunger strike.

Arnaldo didn’t participate in the fast. His task, on that and other occasions, was organizational and logistical. On March 17, 2003, the day before Fidel Castro — taking advantage of the fact that the international meda gave priority to the U.S. invasion of Iraq — would decide to unleash the most brutal operation against the dissident movement and independent journalism on the Island, Arnaldo and Tania met in the little apartment of Jesús Yánez Pelletier, on Calle Humboldt, around the corner from the Vedado Hotel.

That morning they had come together for a press conference with hunger strikers, and among those present were two supposed dissidents who were part of the Assembly to Promote Civil Society: Aleida Godínez and Alicia Zamora, who, in April 2003, would be “outed” as agents of State Security.

That morning, Tania remembers, Arnaldo had bought a copy of the newspaper Granma from a vendor at Infanta and San Lázaro. “And he showed me an article or an editorial, I don’t remember exactly, and commented that it gave him chills, that the Regime was cooking up something huge against the dissidence.”

Twenty-four hours later, Castro began the ferocious wave of repression that is still known today as the Black Spring of 2003. Among the 75 detained was Arnaldo Ramos, who had just turned 61.

His body paid the price of the almost eight years that he passed unjustly and cruelly incarcerated. But not his strength of spirit as a citizen, economist and dissident. In the three prisons where he was — Sancti Spiritus, Holguín and the last six months in Havana — he went on hunger strikes and protests, with political as well as common prisoners. But the most important thing was that in all that time he didn’t stop reading, analyzing and writing.

On three or four occasions, through his wife or the families of other prisoners, he sent his writings to Tania Quintero, so she could type them and send them out. They weren’t simply hand-written sheets of school notebooks. They were analyses of the socio-economic and political situations in Cuba. Texts that were drafted in the gloom of the cell. Annotations that he made after reading the first and last pages of the official press, the only one permitted in Cuban prisons.

It was very important for Arnaldo that his family, as well as bringing him a bag of non-perishable food so he could survive in miserable conditions, also brought him, although they were back issues, the newspapers Granma, Juventud Rebelde, Trabajadores, and the magazine Bohemia.

In November 2010, Arnaldo Ramos was released from prison, and I interviewed him for the newspaper El Mundo. In the apartment where he now was living, I could see the boxes where for years he archived the newspapers and magazines that he knew how to read between the lines and extract data that allowed him to discover the true economic situation of the country.

“When they detained me, on March 19, 2003, it was around 9:00 in the morning, and State Security spent five hours requisitioning papers and documents,” he told me. I reproduce here the first two paragraphs of that interview:

“He returned home on a Saturday. After seven years and eight months behind the bars of a cell and the squeaking of Chinese padlocks, the economist Arnaldo Ramos Lauzurique, 68 years old, at 6:30 in the morning of his first Sunday in liberty, sat down in the park situated in front of the modest building where he lives, in the neighborhood of Centro Habana.

“He wanted to contemplate the dawn, breathe fresh air and see ordinary people carrying their bags to do their Sunday shopping. He wanted to feel like a free man. After two hours of meditation, the sun began to heat up the morning, and the noise of the kids with their bats, balls, roller skates and soccer balls broke his personal spell.

“Then he began what was always his daily routine. Standing in the tiresome line to buy the official press at a nearby kiosk. It’s one of his manias. Gathering the daily Cuban newspapers and archiving them in a box.”

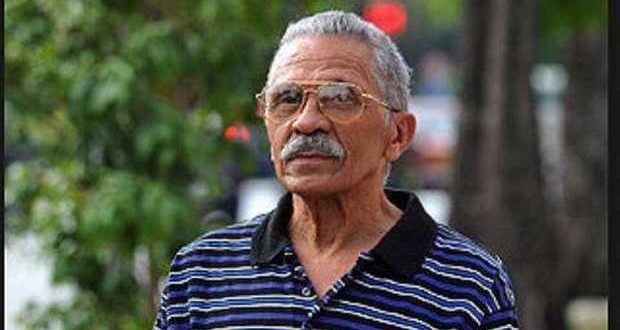

This mulato was born May 27, 1942 and died on November 3, 2016 in Havana, his native city. He lived in a tenement and made something of himself, overcoming poverty and prejudice. He managed to become an economist, marry a woman who also studied and graduated as a doctor, specializing in radiology, had two children and grandchildren and formed a solid family. He stays with me in his writings, which can be found on the Internet and in numerous blogs and digital sites.

But, above all, I am left with knowing what an extraordinary human being Arnaldo Ramos was, with incredible memory, simplicity and modesty. He has more learning and talent than most of the dissidents who surrounded him, but he always stayed behind the scenes. He had a humility that the present dissident movement lacks, where there are so many who get off on selfies, headlines and having the title of “leader.”

Photo: Arnaldo Ramos Lauzurique. Taken from the Facebook page of Martha Beatriz Roque Cabello.

Translated by Regina Anavy