The Minister of Education, Ena Elsa Velázquez, is hoping to turn corruption and academic fraud in Cuban schools around.

The Minister of Education, Ena Elsa Velázquez, is hoping to turn corruption and academic fraud in Cuban schools around.

In her tour through several provinces to check on preparations for the new school term beginning on September 2, Velázquez highlighted the “social commitment of teachers and professors” to address illegalities and acts of corruption.

She spoke of strengthening families’ confidence in the educational system and confronting “scholastic fraud and other more subtle and nefarious distortions.”

This requires great political and oratorical skill in analyzing the conditions that for years have affected education on the island, to say nothing of the low salaries paid to teachers.

As always in Cuba, one must separate demagoguery from reality. The complacency of government officials causes them to suffer from an irreversible myopia.

They only see the successes. And they do exist. For a third-world country, it is laudable to be able to provide free education and public health. We may be better than Burma or Haiti, but there has been a qualitative reversal in sectors which once were showpieces of the Revolution.

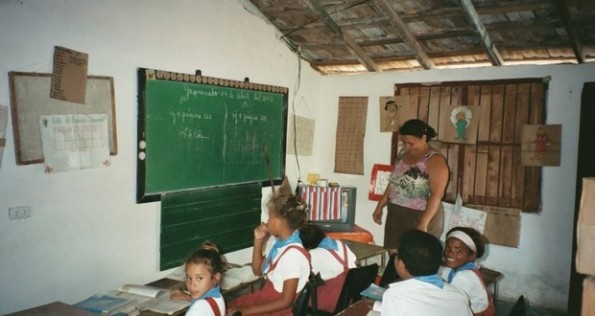

There are schools but they lack good instructors, teaching material has to be recycled, the merienda* has been eliminated in primary schools, and lunch for boarding students is wretched.

And we have not even talked about the extreme politicization and ideological content in course material and extracurricular activities. These include everything from classes on how to load an AKM assault rifle to fundraising for self-defense militias.

Too often the Cuban government likes to remind us that education and health care are free. These are the cornerstones of the socialist model that the world sees.

They are, however, distortions of reality. The state can subsidize the health and education system thanks to the high tax rate it imposes on workers. In countries where students pay not one penny towards the cost of their education, the money to fund this “privilege” must come out of the taxpayers’ pocketbooks.

But this is not the case with Cuba. A percentage of the ridiculously low salaries paid to workers and employees, excessive taxes on the self-employed and import duties of up to 300% on hard-currency remittances subsidize a significant portion of the national educational system.

However, everyone who one way or another contributes to society — whether it be by cutting cane or spending dollars they have received from relatives in Miami — can and should demand a better education for their children.

For a decade primary, secondary and pre-university education has been in marked decline. Because of poor wages and low social status many instructors go to work as porters in five-star hotels or as fry cooks in a street-side stalls.

It is inconceivable that a policeman or armed forces officer would make close to 900 Cuban pesos a month — not counting their ability to acquire groceries, cleaning supplies and clothing at low prices, or to stay in exclusive recreational villas — while a professor at a secondary school makes only Cuban 350 to 400 pesos a month.

The teaching profession is one that is not highly valued in Cuba. It is not an attractive alternative for university graduates. Only when there is no other option, or when men are trying to evade military service, do young people choose to study pedagogy.

The new school term will begin on Monday, September 2 in schools which have received a fresh coat of cheap paint, whose furniture and windows have been repaired and whose families have put aside some money for their children’s meriendas. Believe me, it is not easy to provide five meriendas a week. Children’s backpacks resemble those of mountain climbers.

The school uniform presents another problem. Some sadistic bureaucrat decided that each student would get a new uniform every two terms. The dim-witted technocrat did not stop to think that in their primary school years children grow quite rapidly. Or that given the heat and the carelessness typical at this age, students often return home with their uniforms in tatters.

The solution was for families to buy uniforms on the black market for five convertible pesos apiece. These are not their only expenses.

In case a child gets a mediocre professor — something now quite common in primary and secondary education — parents must pay ten convertible pesos a month to a retired teacher to tutor him after school.

As the Minister of Education follows her road map through the country, checking on preparations for the next school term, teachers are hoping the official will agree with them and announce a salary increase.

Teaching remains the worst paid profession in Cuba.

Iván García

Photo: Cubanet

*Translator’s note: A traditional afternoon snack or light meal somewhat comparable to tea time.

28 August 2013