![]() 14ymedio, Juan Diego Rodriguez, Havana, 11 August 2020 — “Yesterday you bought ground meat, today you can only buy tomato puree,” warns an employee after scanning the identity card of a woman who is waiting to enter a store in Centro Habana. With the Portero app — the word means ’doorkeeper’ — installed on their mobiles, hundreds of state workers are trying to organize the lines and detect possible hoarders.

14ymedio, Juan Diego Rodriguez, Havana, 11 August 2020 — “Yesterday you bought ground meat, today you can only buy tomato puree,” warns an employee after scanning the identity card of a woman who is waiting to enter a store in Centro Habana. With the Portero app — the word means ’doorkeeper’ — installed on their mobiles, hundreds of state workers are trying to organize the lines and detect possible hoarders.

In the lines at the doors of the stores, the majority are female faces, grandmothers and mothers who carry on their shoulders the responsibility of bringing food home amid the shortages exacerbated by the pandemic. The identity card is essential for them to access markets but it can also prevent access.

On August 2 the authorities began an offensive in Havana which they call “Operation to fight against coleros,” referring to those who supplement their income by standing in line for others. One of the main tools in this battle is an application created at the University of Informatics Sciences (UCI) that records what day a customer accessed a store and can warn if they are behaving like a reseller.

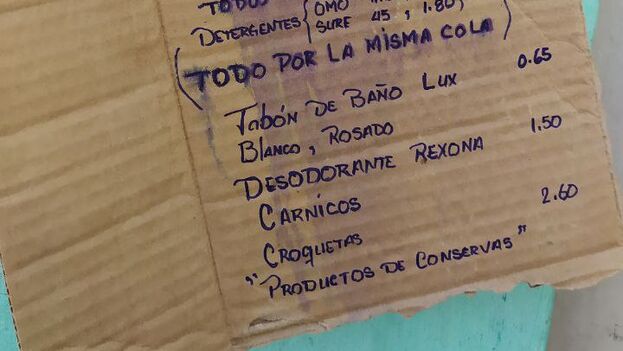

Despite the controls and health warnings, many of the lines to buy food and hygiene products continue to be crowded and chaotic, a potentially dangerous situation amid a rebound in positive cases due to Covid-19, which has forced the implementation in Havana of stricter measures to try to stop the contagion.

Although public transport is canceled, private businesses are closed and the police presence in the streets is notably greater, the authorities have not been able to reduce the lines. If anything, they try to organize them and intimidate those who make a modus vivendi out of the line, buying the same product several times and then selling it on the black market.

The Portero app is a line organizer that uses mobile terminals to read the QR code on identity cards. On displaying the document, the application stores the information in a database that is used to sort the line, but also gives clues to the authorities about the behavior of users: where they buy and how often.

“We decided to create this app to maintain order in the establishments that sell products. We wanted to provide a solution related to technology, but without making it too complicated, or inventing a cyber-ration card or requiring hardware resources (servers, networks, etc.),” explained Allan Pierra Fuentes, one of the engineers who created Portero, speaking to the official press last April.

However, the tool is being used for much more than just organizing the lines.

The new version of Portero is linked to the databases of the Ministry of the Interior where criminal activity is collected. The app “is already used at 135 stores to confront citizens who carry out the activity of coleros and other categories of interest” to the police, warned a note published on the local government website.

The scanning of the identity cards “made it possible to identify more than 949 people, 310 coleros, 81 control targets, 309 tax debtors, 152 fine debtors, 48 people being searched for, one whose document belonged to a deceased and another 48 who are on probation,” the text explains.

“They checked my card twice,” Javier, a 36-year-old from Havana, tells this newspaper on the weekend, when he decided to go buy some food at the La Puntilla foreign exchange market, in the municipality of Playa. “When I entered, they scanned my document and when I went to pay at the cashier the employee checked my card again.”

Javier fears that “now they know what day I went to which store and even what I bought; I don’t know what they are going to do with that information, but I don’t think anything good,” he believes. “If those stores sell only dollars and it is assumed that the merchandise is not rationed, why then do they control who enters and how many times a week they go.”

In other stores, the employee who scans the identity document keeps it and only hands it back to the customer when they are about to pay at the cash register.

The current Cuban Constitution, ratified in 2019, includes the right to respect personal and family privacy, image, voice, honor and personal identity, but in the midst of the crisis unleashed by Covid-19 on the island, many fear that private information is another of the many victims of the tightening of controls over society.

“The volume of information they are collecting is impressive,” warns computer engineer Pablo Domínguez, who has worked on the development of several applications for the private sector. “At the end of the day, the list of registered identity cards can be exported from each terminal,” he explains to this newspaper.

“If the person already bought in that store that same day, then an alarm goes off and the employee is warned that he may be facing a hoarder,” he adds. “But in Cuba the care and protection of personal data is a pending issue and we have the right to ask ourselves what will happen to all that information.”

Domínguez recalls that for years the database with the numbers, private addresses and full names of the clients of the state Telecommunications Company (Etecsa) has been leaked to the informal market. And she asks: “What is going to happen when this information is leaked and on the street people can know not only your identity card number and your full name, but also where you shop?”

______________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.