Iván García, 6 March 2017 — A sloppy piece of cardboard painted with a crayon announces the sale of a discolored house in the neighborhood of La Vibora, 30 minutes by car south of Havana.

If Amanda, the owner, who is raving poor, manages to sell the house for the equivalent of 40,000 dollars, she intends to buy two small apartments, one for her daughter and the other for her son.

The house urgently needs substantial repairs. But Amanda’s family doesn’t have the money needed to undertake the work. Frank, 36, her son, is the custodian of a secondary school and earns a monthly salary of 365 Cuban pesos, around 17 dollars, and to help support the family, he’s a blood donor.

The Cuban regime doesn’t pay for these donations. Frank, who gives blood up to two times a month, should receive some 10 pounds of meat, a half-kilo of fish and three pounds of chicken.

“There are always delays. It’s a pain. In every municipality there’s a warehouse assigned to distribute this food to the blood donors. But it never happens. And what is worse, the government doesn’t reinstate you. For example, you never receive fish. Several of us donors sent a letter to the Ministry of Public Health complaining about the lack of supplies, but we’ve never received an answer,” complains Frank.

The material insecurity in Cuba is brutal. A growing number of families have furniture in their homes that is half a century old, or more. They lack modern appliances and must make their clothing and shoes last forever.

But the biggest problem is food, which devours between 80 and 90 percent of the average salary, which, according to official data, is the equivalent of 26 dollars a month.

Odalys, a nurse in a blood bank, says that “most volunteer donors give blood in order to take some food home. There are also people who occasionally give blood in order to receive a little snack of ham and cheese and a soft drink.”

The CDRs (Committees for the Defense of the Revolution) are paramilitary organizations, created as embryos of support for special services, to collect commodities. They also conduct night patrols to expose dissidents and those suspected of “illicit enrichment,” an aberrant judicial heading applied by the Castro government to any person who improves his quality of life.

Also, the CDRs have campaigns for blood donations. A resident of Lawton, the president of a CDR, affirms that “every time there are fewer people who want to donate blood. The CDRs have become a mess. They’re only busy snitching on the dissidents. They haven’t done night duty for some time on my block, much less organized recreational activities.”

Danaisis, who’s been a doctor for three years, recognizes that “even in the large hospitals in Havana, where there are dozens of surgical interventions every day, they don’t have sufficient plasma in their blood banks. When a patient has to have an operation, family members must donate blood. Or buy it from people at 20 dollars a donation.”

Like Frank and the rest of blood donors in the 10 de Octubre municipality, the nurse, Odalys, and the doctor, Danaisis, don’t know that the State exports, annually, hundreds of millions of dollars worth of human blood derivatives.

According to María Welau, the executive director of the Cuba Archive project, in an article published June 4, 2016, in Diario de Cuba, “For decades, the Cuban State has coordinated a multimillion dollar business, based on the commerce of blood extracted from its citizens, who ignore this trafficking and don’t receive any remuneration for their donations. Already in the middle of the 1960s, reports indicate that Cuba sold blood to Vietnam and Canada. In 1995, Cuba exported blood worth 30.1 million US dollars, and this commerce represented its fifth export product, surpassed only by sugar, nickel, shellfish and cigars.”

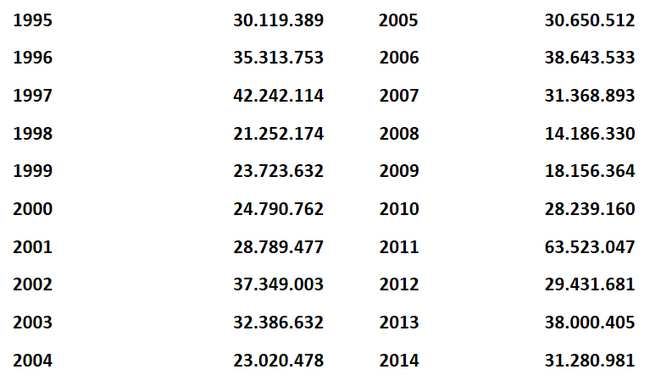

Werlau provides figures. “These exports don’t appear in the official statistics of the Cuban Government, published by the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI), but data from the world commerce indicate that in the 20 years between 1995 and 2014, Cuba exported 622.5 million dollars worth of human blood derivatives — which gives an average of 31 million dollars a year — under the category of Uniform Classification for International Commerce (SITC 3002), for human blood components (plasma, etc.) and medical products derived from plasma (PDMP is the acronym in English).

Cuba: Exports of human or animal blood prepared for therapeutic uses (in dollars)

In this article, the Cuba Archive Director denounces the fact that “the largest amount of these exports has been allocated to countries whose authoritarian governments are political allies of Cuba, probably to state entities that apply less strict criteria and have the same ethical standards (Iran, Russia, Vietnam, Algeria until 2003; then to Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina and Ecuador).

“According to Cuban Government reports, 93 percent of all units of human blood collected are broken into their components, which permits a much more lucrative business than if only plasma is sold, and facilitates the production of derivatives of high value, like interferon, human albumin, immunoglobulins, clotting factors, toxins, vaccinations and other pharmaceutical products. This export commerce gives Cuba a considerable advantage over its competitors, because it saves the usual cost represented by payments to the doors, whose blood is the raw material of the business.”

Exporting plasma, whether animal or human, isn’t a crime. What’s despicable is the lack of transparency of Raúl Castro’s regime. Or that Cubans like Frank have to give blood in exchange for a handful of meat and a few pounds of chicken. Food that the State doesn’t deliver most of the time.

Translated by Regina Anavy