![]() 14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, 29 November 2016 – Under the shadow of national mourning after the death of Fidel Castro, Cubans have been called to sign, as an oath, some words spoken by the former president in May of 2000, in which he left for posterity his concept of Revolution.

14ymedio, Reinaldo Escobar, Havana, 29 November 2016 – Under the shadow of national mourning after the death of Fidel Castro, Cubans have been called to sign, as an oath, some words spoken by the former president in May of 2000, in which he left for posterity his concept of Revolution.

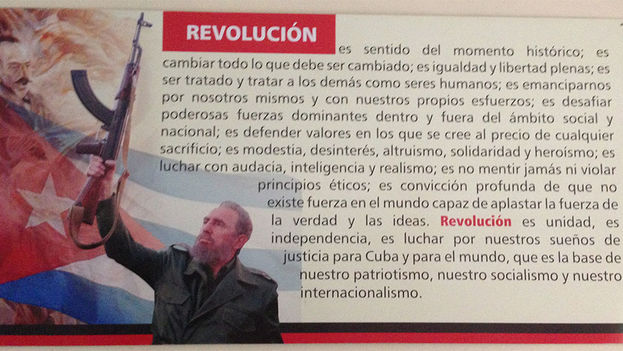

“Revolution is a sense of the historic moment; it is changing everything that must be changed; it is full equality and freedom; it is being treated and treating others as human beings; it is emancipating ourselves by our own efforts; it is challenging powerful dominant forces within and outside the social and national sphere; it is defending the values we believe in at the price of any sacrifice; it is modesty, selflessness, altruism, solidarity and heroism; it is fighting with audacity, intelligence and realism; it is never lying nor violating ethical principles; it is a profound conviction that there is no force in the world capable of crushing the force of truth and ideas. Revolution is unity, it is independence, it is fighting for our dreams of justice for Cuba and the world, which is the foundation of our patriotism, our socialism and our internationalism.”

More than a definition, the text should be understood as a personal assessment of the political process in which Fidel Castro played the starring role. In the absence of a solid theoretical thought, the exegetes of the Commander in Chief have made use of the poetics of his rhetoric to extract, something like that, as a political testament.

The phrase chosen has the turns of an oratory delivered to captivate those congregated in a plaza, where almost all license is permitted, while sounding good and conquering the ears. But read at a distance and analyzed as a thesis, it lacks programmatic solidity.

In the phrase, the term Revolution is ambivalent and is presented both as a result obtained and reached for. At other moments the statement seems a method to achieve certain goals, the final fruit of a process, or a tie to moral values close to the Decalogue of good behavior.

The contradictions of the concept stated by Castro for more than fifteen years ago have discouraged academics of the official environment and organic intellectuals from analyzing it. Instead, they have chosen to sanctify the verse so as not to be seen to be committed to rigorously dissect it.

When Castro mentions that Revolution is the sense of the historic moment, it only confirms that he lacks the political instinct to perceive the wealth of opportunities that such processes trigger, something that rests exclusively in the capacity of certain individuals to take advantage of the situation.

On the other hand, the substantial difference between Revolution and reform resides in the way transformations are realized, but these words avoid pointing out the violent and radical character of the process they promote. The absence of this precision constitutes the most important conceptual deficit of the text.

In the horizon of almost all social revolutions is equality, but a process of such a nature is not needed to try to achieve it. Freedom has historically been most affected by revolutions. In particular, the freedoms of expression and association, and, in the case of socialist revolutions, economic freedoms.

The inaccuracies in the text does not end there.

In the words extolled today, Castro defines his creature as the capacity to treat others and to be treated as human beings. It is the promise of the lowest profile that a politician could project and, most obvious, that includes a concept for posterity that is, at least, a disturbing gesture.

The confusion rises in tone when the leader invites us to “emancipate ourselves by our own efforts,” without specifying if he speaks from the working class that must shake off the “chains” of exploitation, or if it is a nationalist-style demand to eliminate dependency on some foreign power.

In the first case, it would be renouncing alliances with other sectors such as the peasantry, while following the second to the letter leads to renouncing proletarian internationalism.

The act of “challenging dominant forces” differs if you are in an insurrectional period, or it is several years after the beginning of the Revolution. When Castro stated this concept, power in Cuba lay in the Communist Party and especially in his own will, which did not accept the slightest challenge.

The voluntarism of the orator stands out when he calls for “paying whatever price necessary,” while he appropriates Christian values by promoting modesty, selflessness, altruism, solidarity and heroism. The call to never lie or violate ethical principles reinforces the character of the commandments of a religion.

The text also extols audacity, intelligence and realism, guidelines that are more appropriate to succeed in business than to drive social transformation. Emphasizing these assertions with the conviction that “there is no force in the world capable of crushing the strength of truth and ideas”: pure idealism, alien to the dialectical materialism of Marxist inspiration.

Unity does not make the Revolution, nor is independence a conquest in the midst of a globalized world that has put an end to borders, so all that is left to the orator to base his concept on is “our patriotism, our socialism and our internationalism “and to fight for “our dreams of justice,” without substantiating any.

The conceptual gap of the definition of Revolution that, as of this Monday, millions of Cubans have signed, leaves their hands free for whatever future decision is taken by whoever relieves the current historic generation. On this foundation stone, one can erect anything.