![]() 14ymedio, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 21 January 2018 — Betania Publishers, in print and digital editions, has released the book La familia Loynaz y Cuba, by Luis García de la Torre, with a prologue by the Cuban essayist and professor Alejandro González Acosta, who is living in Mexico.

14ymedio, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 21 January 2018 — Betania Publishers, in print and digital editions, has released the book La familia Loynaz y Cuba, by Luis García de la Torre, with a prologue by the Cuban essayist and professor Alejandro González Acosta, who is living in Mexico.

In this book we are given a lucid and fascinating overview of the Loynaz family, one of the most literary families in the history of Cuba, from the father, Enrique Loynaz del Castillo, General of the Liberation Army, to Dulce María, his eldest daughter, and her siblings: Enrique, Carlos and Flor.

In his prologue, Alejandro González Acosta describes the book as the chronicle of the Loynaz family and also the “homage to a way of being, of feeling and being in Cuba that no longer exist and may never be again.”

Luis Garcia de la Torre (born 1973, Havana) is a poet and teacher living in Santiago de Chile, where he teaches Language and Communications at the University of Chile. He is the author of the book of poetry Rave Party (2002).

We reproduce the last chapter of the volume with permission of the author.

Chapter 5: Flor and Dulce deconstruct a happy old year

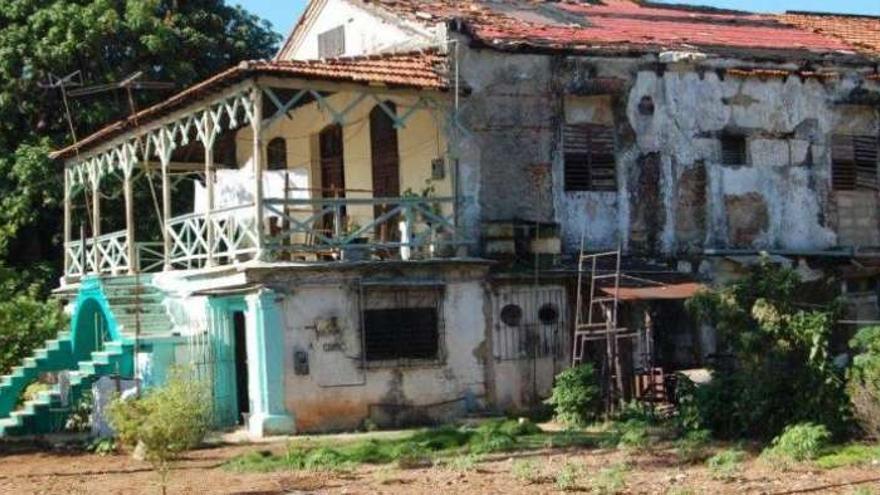

The house is at Línea and 14th streets. Almost gone. A worn out husk in ruins is what you see. And vice versa. The mediocrity of physically erasing a property of this lineage, at that time youthful, that did not let itself be taken, neither when young nor later already old, for the remains of that other Havana. Children of the most intrepid Latin and mambisa descent. The house weathered by the salt and bad taste of more than half a century. The literature, however, exalted.

There, many figures of Latin American and Hispanic letters sipped sweet lemonade. They made progress on masterpieces that their respective countries had taken for themselves. Defending each child and boasting that their land had yielded such talent.

However, today, go to the City of Havana in Cuba, seek out the Vedado neighborhood, come to Línea and 14th and you will understand two things: one, why it is impossible for me to mark the neglect that socially symbolizes the house in this paragraph; and two, you will see how these remains of the manorial palace are the revenge, the anti-system response to those who still believe that there was some redress for them.

On Calle 19, after being inhabited since 1947, and then 1959 arrived, and from 1960 to 1997 there is a voluntary cloistering, a cloistering convinced that it was better not to look outside, neither personally nor socially, at what was happening, or what was frustrated.

Decades of social violence against individuals, or against property, which is the same. Years of silencing in an environment characterized by literary talent unparalleled to this day, and mambisa history as it would not exist in life until its death. And on 19th, for almost half a century everyone saw when they passed by, this baronial house asleep in carelessness and filth. As of February 5, 2005 it has served as a cultural center. A place of literary promotion.

After inhabiting the house for 57 years, the connection to its railings, its walls, its arches, its tiles, its conversations is too much, and the place then becomes its inhabitant and its inhabitant breathes and feels for its stones. They joined together: one a symbol of the other, one the root and the trunk of the other.

And today, it is the house in better physical condition or ravaged, spiritually decayed or chimerical, what was lived in it was so hard that it will manifest itself constantly and forever in the sublime of its confines, in its history, in Vedado and in the whole of Cuba.

And in La Quinta the flow doesn’t stop, it is an air of imaginations. Alquimia, Ruiz de la Tejera, Lichi, Edmundo, Gabo, Birri, Ullmann, Brandauer, Pérez, Titón, Chijona, Daicich, Cumaná and hundreds of the most important artists in the world.

From the inheritance of days past, in the hall, a small medallion that was broken and a cabinet located by the entrance. Then there was the monumental staircase with the armor Tatar at the base of it. A knight’s armor and six ancient paintings. Very old. Very faded by time. Very withered.

When you passed the vestibule, then, passing the entrance, there was an enormous Saint Michael the Archangel slaying a bronze dragon. You climbed the stairs and found a hall that gave access to two rooms with a kind of shabby library. The rooms were guest rooms. In the one on the right, rotating one hundred and eighty degrees, a chapel. It was a monumental feeling.

The chapel was a hall like all the churches in Havana had. It had been made up of all the churches, the old convents, the stained glass of Santa Teresa, Santa Catalina de Siena, Santa Clara.

They went to all the places in Old Havana for more than fifty years buying, a woman named Doña María. A Spanish antiquarian residing in the El Ras house. They had made a true chapel where angels of the seventeenth century were preserved, authentic pictures of religious images, votive offerings of nuns. There was an abundance of fabulous pieces. And it was even arranged with pews, kneelers. Curious things.

Before Los Sobrevivientes — The Survivors — came the house was in ruins. There were many objects. Porcelains, there were marvelous broken porcelains, innumerable. Alabaster vases. Headless sculptures. There were a great many, like six. Before climbing the stairs you passed the all, there were two bedrooms filled with odds and ends, with junk. And down the hallway, the last room, it was Flor’s. It was astonishing. A neoclassical bed. A display case. A dressing table. A really amazing amount of papers.

It was Flor’s real archive. A fabulous archive. Papers that were in that room along with the coffin. A coffin made from old woods. She said she used to take a nap in it. She was a joker. With Flor there really was a sense that time never ended. Flor was a woman with a lot to say. She said it. But she didn’t say everything. Or she half-said it. Or, also, she feared giving some interpretation.

She had led her life a little lightly. She had tempted society. She had been a leading woman in Havana society. She didn’t have the tastes of a housewife. She had style and aesthetics. She hadn’t held on to family tradition like Dulce María.

The strength Flor had to face life was the silence in which she kept everything. She kept huge silences, because she experienced everything. God knows all the prophecies Flor experienced around all those characters. And many of them she didn’t tell us about. So now, perhaps, we can’t capture it.

The people who went to La Quinta didn’t have the breadth. The parties were open and less distinguished in terms of the audience and the people. At La Quinta people came who weren’t of the same social world. They came to have fun. With Ducle María it was the opposite.

Dulce María’s gatherings, before the Revolution in 1959, are all documented in La Marina newspaper in the National Library of Cuba. They are on all the social pages. When Dulce María received, because of the position of her husband, she had to receive every illustrious personality that came to Havana, and they were recorded in the corresponding Havana Social Chronicle. So, before 1959, Dulce María had a social world. From 1946 to 1959, who did Dulce María not receive on Calle 19?

But the people who went to Calle 19 were not the people who went to Quinta Santa Bárbara. The world of the architect was not the world of the well-known, because Dulce María had to lead every dialogue, every conversation. There is a wedding album published in the Canary Islands. The second wedding album by Dulce María.

The salons of Dulce María from 1957 to 1959 are in this album. All of society came. For example, Lily Hidalgo de Conill, the Ponce de Leóns, the illustrious surnames the Montalvos, the Sarrás. Everyone from a very notable social world: businessmen, people of letters, the publishers Ateneo, Chacón and Calvo, Arts and Letters, the University of Villanueva and the University of Havana. The old surnames: Aguas Claras, Josefina de Cárdenas, Raúl de Cárdenas and Rosita Jibacoa de Marco.

There were these gatherings. Dulce María gave a lot of parties. Because the atmosphere she gave to parties and social and aesthetic gatherings was produced by the sense of being people of class. To attract to your home the crème de la crème of those who passed through Havana. Or who lived there. But Flor never had a social reputation, nor the social touch of Dulce María. Flor was seen in Havana society as a weirdo. As an uncultivated object. Notorious. Nobody approached Flor.

At the gatherings at la Quinta the drinks were served straight. They were quiet. They did not have an altruistic purpose. Flor’s marriage lasted a short time. And these things she did alone, with men friends and some women friends who were not friends of Dulce María, or were not Dulce María’s environment. The relationship between them was at times tense. It was hard. There were times they didn’t speak.

It was difficult. Dulce stayed like this for a while. On 19th there was a nunciature. Dulce Maria had a funerary sense for the hours. For the passage of time. There were moments in conversations where she was very absent and could not be addressed. You could not ask. You had to listen to what she wanted to say.

Flor was obliged to spend days at 19th and days at Santa Barbara. She feared, not the alienation, but the remoteness that assaulted the house. It happened on several occasion. There was no guard. She could not handle money. Often people would come with some little piece of paper: “Dulce María gives five pesos to the bearer.” This was Flor’s way of financial communication. All the money was concentrated at 19th.

Dulce María administered the minimum expenses of Santa Bárbara. There was a sense of patriarchy, or of matriarchy, of Dulce María with respect to her siblings. Flor was not a completely realized creature. She was overwhelmed by the presence of Dulce María. In front of a very nice portrait in the dining room of the Santa Barbara house, of a very young Dulce María, Flor drank her coffee. Seated at a large rosewood dining table with twelve chairs. Also in front the painting “The Torture of Guatimozín,” where there were all the First Editions, she drank her coffee and was very afraid.

She had confessed so much to God because she had always been very envious of the talent that God had given to Dulce and not to her. And she also felt that Dulce knew how to do everything and she did not. Dulce María, I should have loved a lot, she said. And she asked God’s grace for the destiny of Dulce María and her triumph. Dulce María had to be eternal. The admiration felt like envy, and it was a punishment. They lived completely different lives. Flor meditated a lot in the dining room. On this and that.

She had her favorite literature there. Books dedicated by Dulce María. And the same in her room. Her room and the dining room were where she spent the most time. She didn’t ever sit outside. She had a certain fear of being observed. Although she was capable of going out at night with the General’s two pistols to see what was in the bushes. She surprised an old man there who afterwards became her servant. She took him prisoner in the house and they became friends over coffee.

Her room was a place of refuge for Flor. The bed was always unmade. And always clean. She was a clean woman. Yes, the house was abandoned, but it looked like it was inhabited by a servant. A house where there is dust, where there are spider webs, but a house where time passes in unison. There were no longer any servants. She was completely alone. The place was really spooky.

She spent seasons in Dulce’s house and then returned again. There was a lot of loneliness. And also at 19th. They were completely alone. It was a heartbreaking loneliness. The Santa Barbara house, for more than 20 years, until it was torn down in 1983, became a depository for objects. Sold very cheaply. Many were given to the National Museum, and to many other institutions. She gave the chapel to Father Fusiño, to be the chapel for the Sancti Spiritu parish. The furniture at La Quinta had been at Línea before.

Much of the furniture, the art objects, the collection of paintings, had been at Linea. This collection, this furniture, went mostly to the farm. As a gift from the family to Flor. Because at Linea they had a house. There was the great house on La Quinta del Aleman, around the corner. When Flor married, she built the pavilion annex. The Eqyptian style pavillion. Flor’s husband, the architect, built it. Flor lived there, in love with him. Later they left for La Quinta Santa Bárbara.

And there was the furniture of Jardín. The writing of Jardín was finished in 1935. There were two manuscripts of this novel. One was published and one was not published. She finished it with a page, “I have written an immortal work, 1935.” Everything that was in Jardín, everything in the houses on Linea, that monumental set, all that furniture was distributed. There wasn’t much for the house on 19th. Dulce felt like keeping some things. But most of it was moved to Santa Barbara. Santa Barbara was like a redoubt of the youthful memory of Jardín. Everything from their childhood went to Santa Barbara.

Flor was an interesting woman. She gave sound advice. She had a sense of real time. That time has to do with the aging of things. That is, things do not have to age, only time. If the moth takes a book and devours it, it is interesting because the moth has done its work on paper.

The gallery of precious paintings ascended the staircase. They were extremely interesting paintings and almost all originals. They were paintings from every kind of skill, from the Flemish school to the Spanish.

They were threadbare. They were beautiful. They were of personalities who had been conquerors, and representatives of the nobility in Cuba. There was a beautiful one of a Spanish gentleman. Also another religious, dark, very beautiful. There were six paintings. Those paintings were already in bad condition, the fabric had all unraveled. But they were paintings that had belonged to a branch of the family and that had been gathered there. For many they are the paintings that were in Jardín.

There was no painting of flowers, nor of fruit, nor of life. They were very austere paintings, very sad. There was no profusion of paintings that weren’t sad. She said that their aging was necessary. They had to deteriorate just because. The moths had to eat them. That Dulce was wrong to keep everything. That it was impossible to keep everything. That those paintings were there and that they would stay on the wall. And indeed they stayed there until her death, very dusty.

Flor did not want them restored. She said no. It wasn’t necessary. Time has to pass. Be it as it may, they had to deteriorate. She had no interest in preserving anything. Absolutely nothing. She had to watch time go by. That is, it was a life that didn’t want to die. She didn’t want to die. Her dying was very hard, it was at 19th.

She did not want to die, but at the same time she wanted all things to be real. Everything to be real. That things had to die and the worm had to eat. Flor had that strong dialogue. She was against restoring, against venerating the past. She revered the past but as life. For example, with the Lorca cup.

The cup in the showcase that was a Lorca, the Jardín tableware. And she remembered when the two of them went at dawn to wake up some poet, or when they drank lemonade in the gardens of the farm. Dulce never wanted to remember or talk about these matters. Those soirées Flor had with Lorca at dawn attracted many people. People from the docks came. Dulce forbade it, Flor was silent. The enigmas. The family secrets could not be told. The brothers who had a happier life. That’s why Lorca came, skipped, played the piano, shouted and laughed in those gardens on Linea. Dulce was bothered by all this.

Santa Barbara was an open palace from the time you entered. Where you saw the sarcophagus and saw Napoleon in his room. There was also San Loynaz. The beautiful image of Saint Martin de Loynaz, who was a martyr in Japan. A Jesuit. The first saint of the family, the patron saint of Guipúzcoa. He was the saint who protected families in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Guipúzcoa. He was a Franciscan martyred by the Japanese and later canonized. He is the saint of that region.

In the year 1946 Dulce María was invited and wrote La excursión a San Loynaz. The poet was not much interested in her family tree, however she had a veneration for San Loynaz. And so she wrote several epistles. All this was bought. The Santa Clara museum ended up with the wonders. It bought an entire life. There you could see some vases with the battles of Napoleon. Gabriel García Márquez bought the house to create the FNCL (New Latin American Foundation) with much of its furniture. It was that of Jardín.

The time after the Revolution didn’t exist. Technology didn’t exist for them. The Revolution remained frozen in time. Dulce María was very close to Juan Marinello. Once they closed the door that opened from E Street to the house on 19th. They said you couldn’t have a house with two doors.

She wrote to Juan Marinello. William Gattorno personally delivered the letter. Juan Marinello ws very loquacious. He looked after the Loynez’ affairs. Juan Marinello he was a true friend to Dulce María, despite the political distances. They felt joined together by some ancestor. From the poetic point of view. From professional respect. Juan answered and helped her.

It was a nice that, despite the fact that they had that link, and there were such characters outside, the Revolution did not enter that place. And so they considered Juan Marinello a great friend. He had an interest in the Loynaz. Of course when you entered the Loynaz house, it was a world of fans, porcelains, another world. When the Revolution triumphed the sisters did not want to see it. They locked themselves in to live and watch.

Dulce María made a short trip to the United States in 1959. She returned immediately and stayed to see what was happening. Your husband traveled. He was absent for 12 years until 1972. He returned to Havana and in 1974 he died. The General’s daughter has no reason to leave the country and was jeered. Many people, and the Revolution, wanted Dulce María to leave Vedado because she was in the way.

But she had friendships although it is a delicate subject. With Mariblanca Sabas Alomá, a very rigid woman, very difficult, but very close. Angelina de Miranda, who was her secretary and companion. Angelina de Miranda was the embodiment of sacred love. If there was a great love for Dulce María, it was the consecrated life of Angelina de Miranda. This does not mean that there has been any kind of carnal connection. But a very beautiful dedication. It was a heavenly love that Angelina de Miranda felt for Dulce María. For more than 52 years.

Flor also had friendships. And with men. She had a friendship with José Zacarías Tallet, with Regino Pedroso, with Monsignor Gaztelu, as her confessor; with Aldo Martínez Malo, who for her was a patron because he managed to domesticate Dulce María, so that Dulce María would write Faith of Life. And he managed to reassure her in her last years, which were terrible years. The years of that silence. Dulce María was about to go crazy in that terrible silence. A silence that the footsteps, the only echo, was the echo of silence, and that silence would have driven her crazy had not Aldo Martínez Malo appeared, who was a counselor to both of them.

There were also other close friends, their contemporaries. But far away because of the exodus. And far away because they couldn’t visit them, like they had before 1959.

Flor died in 1985, at 77. She never aged. She always stayed the same: her face, her subtleties. Just the same until she became a little stick that was destroyed. She was drying up. And she didn’t paint. She was very thin. Her way of dressing very lightly, antique dresses unaltered, suit jackets in summer, very bright colors.

Dulce María had a great way of dressing. She had kept the lines of a more interesting body. She was more slender. And above all she had a dignity in the way she dressed that immediately said she was a great lady. She had clothes made for her by Balenciaga and Christian Dior. With everything seen to.

Flor did not show herself off with feminine coquetry. Neither of them wore fabrics from after 1959, or shoes from after 1959. They dressed from antique closets. They were stranded in time. Dulce was truly beautiful. Flor was ugly. Dulce had a beautifully enigmatic magnetism. She was a woman who would have drawn attention in a crowd.

Flor’s gaze was deep and sincere. Filled with pain. She would have wanted to be a different woman. But life didn’t let her and she didn’t let herself. She was suffering, resigned. She enjoyed a drink, picaresque conversations, friendly, a good reader, talking about poetry, talking about the news.

The two were more aware of the world, although they could not talk. The last years they interested themselves in books, press clippings, cultural events. The arrival of Gabriel García Márquez to Cuba. The interview with him when he visited them. They read to García Márquez. From her fabulous novel, and he was very attentive to her.

And Dulce Maria said that she was an antecedent because she had given in Jardín an antecedent of magical realism. She also enjoyed novelties that were temporary, they were not great news, they were events that echoed. When Ian Gibson, the famous historian of Lorca, was in Havana.

She interviewed him about his brother’s homosexuality. It was much commented on how she enjoyed that interview. Gibson left and was convinced that nothing had happened with Dulce María and Flor’s brother. Nothing between him and Lorca. This was published in the ABC of Madrid.

There was a victory in the dialogue with Gibson. He was a man who wanted Dulce Maria to refresh his memory and say private things. Dulce María convinced him not to. A very tough dialogue that was published in the ABC of Madrid.

And when the world accused her of burning the manuscripts of El Público she fought. She had not burned it, it was Carlos Manuel who burned them. He burned them among many documents that he threw to the leaves. Dulce María called a lot of attention to that. Then, in ’92, was when it most grabbed the world’s attention.

In the end, Flor knew she had cancer. She said: “I have a lump here.” And in the kitchen, with three or four potatoes in a bag, she took them and took care of Dulce: “Right now I’m going to make mashed potatoes that she likes very much because Dulce is writing and when Dulce writes, we have to be quiet.”

They felt no distance between them. There was something that could not be said and she wanted to say something that could not be understood and it was farewell. It was six months of agony. Flor stressed the fate of things. They were very affectionate. They were very affectionate and very close.

Dulce Maria did not have time for anything except taking care of her sister. The house was locked and there was no noise in that house. Dulce did not come downstairs. Flor was already in her last days, that tumor was immense.

She had shown it, she had shown it before, it was terrible for Dulce to understand that she was going to be alone. After Flor’s death, Dulce was very hurt because the press, and everyone else, had taken little notice of Flor. Neither Gabriel García Márquez nor the Foundation of the New Latin American Cinema had cared about her. There had been no interest in the figure of Flor. It was a lot. She had a lot of resentment, affection, a life. It was a lot because silence is sometimes gloomy.

Sometimes you have to say things. The silence between the two of them was gloomy, for decades. Sometimes it is necessary to be frank with people. To say things so that they do not remain unsaid. They were afraid to say things face to face. They were said in a measured way. They did not tell the whole truth.

There were very loud moments, of pain, and on the death of Flor Dulce wrote: “I do not know if I am myself or if I am half her.” Speaking about the weight of a surname, a lineage, of everything, everything. She was truly fearful already.

Then came the Cervantes Prize. As we all know in 1992, and the death of Flor was in 1985, seven years before 1992. Dulce was able to withstand the ravages of life.

There is a very interesting letter about the prize, an unpublishable letter about the prize: “… you do not have to be sad because I am not, thirty years of silence and silencing is not the same, but clearly I have not competed for the Prize, it has been awarded for the greatness of silence…”

_____________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.