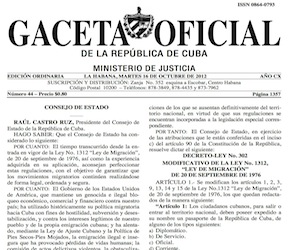

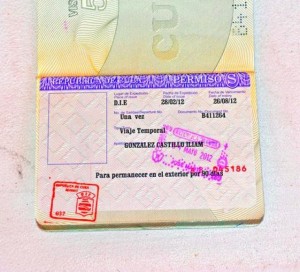

HAVANA, Cuba, 14 January 2014.www.cubanet.org – It’s often said that the elimination of the White Card — as the government-issued travel permit was known — has been one of the most significant among the reforms undertaken in Cuba during the dynasty of Castro II. I don’t believe there are a lot of reasons to discuss it. Things are more or less significant according to one’s values, and it’s natural that everyone values them according to their own criteria and interests that influence their circumstances.

HAVANA, Cuba, 14 January 2014.www.cubanet.org – It’s often said that the elimination of the White Card — as the government-issued travel permit was known — has been one of the most significant among the reforms undertaken in Cuba during the dynasty of Castro II. I don’t believe there are a lot of reasons to discuss it. Things are more or less significant according to one’s values, and it’s natural that everyone values them according to their own criteria and interests that influence their circumstances.

In any case, far from being something to be proud of, I find it shameful that the most significant achievement by a government is to abolish a medieval edict, imposed and maintained for decades by its own system of power, when it would have been a museum piece in any other country in the world.

The opposition

Since this patch was applied, we recognize the benefits it has brought us so far. For the opponents of the regime, controversies aside, it paved the way for them to be able to clarify their thinking before the world. Whether they’ve done it well or poorly, or simply squandered the opportunity, is entirely their own concern. For intellectuals and artists it has undeniably gone well, especially for those who have the means or the sponsors to cover the costs. And it has also gone well for people who, with help from abroad, decided to explore the labor markets and the possibilities of settling in the United States, Latin America or Europe.

Since this patch was applied, we recognize the benefits it has brought us so far. For the opponents of the regime, controversies aside, it paved the way for them to be able to clarify their thinking before the world. Whether they’ve done it well or poorly, or simply squandered the opportunity, is entirely their own concern. For intellectuals and artists it has undeniably gone well, especially for those who have the means or the sponsors to cover the costs. And it has also gone well for people who, with help from abroad, decided to explore the labor markets and the possibilities of settling in the United States, Latin America or Europe.

Thanks to the Castro II Dynasty’s we were allowed to travel more or less freely, and it also allowed, more or less, the temporary or permanent return of those who left the Island years ago, and has improved, more or less, the ties among the Cuban family, so dispersed and fractured thanks to politics. And the measure was useful, until recently, in supporting some enterprising countrymen in bringing from abroad clothes and other products missing here, to market them outside the inane and bloodsucking State-owned stores.

What this immigration and travel reform has meant for the rest of the population, which the majority, remains to be seen; these are people without resources and without relatives or associates abroad, workers, students, ordinary employed and unemployed, too many of them blacks, people on the margin, for the most part needy.

What this immigration and travel reform has meant for the rest of the population, which the majority, remains to be seen; these are people without resources and without relatives or associates abroad, workers, students, ordinary employed and unemployed, too many of them blacks, people on the margin, for the most part needy.

Since I don’t trust the results of surveys carried out in Cuba, where governmental secrecy and repression mean that anyone can make up the testimony of people whose identities and photographs they’re not obliged to publish, I chose to undertake my own quasi-survey among ordinary people living in the Havana municipalities of Centro Habana, Plaza and La Lisa. So, taking into account beforehand the logical distrust of my readers, allow me to offer some opinions collected through informal chats, on the street and in the homes of friends and acquaintances.

Young people

For example, among the young people I asked (about 40), there were two typical attitudes that prevailed: those who answered with some nonsense, such as “it fits,” or “it works, it works,” (mid-level students, generally), and those who see the measure as something positive, although they’re worried looking to the near future, that the immigration process cannot be paid for in national currency (Cuban pesos) and that the prices charge aren’t affordable given the real possibilities of most people.

Housewives consulted (58) almost all agreed that immigration and travel reform is low on their list of priorities, compared to other measures, such as the widening of opportunities for self-employment, or like the simple (?!) fact that for the first time in 50 years bread is being sold of the ration book, and it’s better although more expensive than rationed bread, and the bakeries have better hours.

Housewives consulted (58) almost all agreed that immigration and travel reform is low on their list of priorities, compared to other measures, such as the widening of opportunities for self-employment, or like the simple (?!) fact that for the first time in 50 years bread is being sold of the ration book, and it’s better although more expensive than rationed bread, and the bakeries have better hours.

All of them praised the elimination of the White Car. And many said, plaintively, that now the barriers to travel are the embassies of other countries, ignoring, or at least not aware, that the denials of visas is due to the fears of those governments before possible waves of migrating Cubans, which is equally the fault of our dictatorial and impoverishing regime, which people want to flee en masses, especial young people, although not only them.

The right to return

Slightly more than 60 women and men who appeared to be roughly working age, offered substantial opinions, the biggest group in my quasi-survey.

Slightly more than 60 women and men who appeared to be roughly working age, offered substantial opinions, the biggest group in my quasi-survey.

The most common was that as long as it does not resolve or at least alleviate the terrible economic crisis that affects most people, the importance of immigration and travel reform will always be relative. They insisted that everyone sees it as a good measure, but there are few who are directly affected by it. Even those who see it as an option, aren’t interested in it except as another variant of the economic struggle, because the Cuban people are deeply lacking in a culture of tourism.

So this measure, in the end, comes to be seen as the law of those who vote with their feet. Meanwhile, those who choose to live here, or those who are left with no other remedy, even if they got the money required to travel, would need to use it to solve more pressing problems: food, housing, small businesses…

Both these latter as well as the bulk of the other respondents, spoke positively of the right of return (for those who traveled or those living abroad) as another of the most positive elements of reform. Meanwhile, only three — all elderly — said they did not agree with the measure because, according to them, it favors the regime much more than the people. And five of my respondents (two women and three men, one of them young) dismissed it out of hand, saying that the poor didn’t need to travel, they need to eat, clothe themselves, have a home and a job that allows them to live without jumping through hoops.

In summary, there were just over 150 opinions, informally collected among ordinary people, neither professionals, artists nor dissidents. And although it’s well known that 100 swallows do not a summer make in a city of two million, they may serve to give a hint of popular opinion on this matter. If the result is not sufficient or credible, what can I do. I am also bounded by my circumstances, so I could barely make use of the chance to describe the landscape with the traces of paint from a broad brush.

For the rest, whether or not this is the most significant reform of the Castro II Dynasty, I believe that it will go down in history, if not for the law that released us from our state as hostages of the regime, at least as something that slightly improved our status, making us hostages with a legal avenue for escape.

José Hugo Fernández, Cubanet, 14 January 2014

Note: Books by the author may be found at http://www.amazon.com/-/e/B003DYC1R0