Right about now, on this Father’s Day, Raúl Borges Álvarez is surely living something similar to what he has been suffering for 17 years, petitioning the prison where one of his two sons is held which will not even concede the possibility of letting him out on parole, to which he is entitled by law — all because of blasted politics!

Right about now, on this Father’s Day, Raúl Borges Álvarez is surely living something similar to what he has been suffering for 17 years, petitioning the prison where one of his two sons is held which will not even concede the possibility of letting him out on parole, to which he is entitled by law — all because of blasted politics!

At Havana’s Santa Rita Church — as at various other churches across the country — mothers, sisters, daughters and friends of many other political prisoners penalized for political differences attempt to gather each Sunday to attend Mass and later march, each holding a gladiolus. According to the latest statistics from the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation (CCDHRN), there are around 71 prisoners on the known list. The women who march for them are known as the Ladies in White.

Other equally brave women known as the “Women Citizens for Democracy” do this at other locations. But Raúl Borges, like other fathers, brothers and friends, will not stand by inert before the valor of these women, and intends to join them in demonstrating his indignation, too.

The last 11 Sundays have been like a battle, with entire brigades sent to counterract these civil and peaceful forces, attacking them as if they were common criminals who must be suppressed. It has not been easy for Raúl. Besides being in his seventies, barely a few years ago he underwent two complicated operations — open-heart surgery on 31 August 2010, and a procedure for a peripheral cerebral infarction, in March 2012.

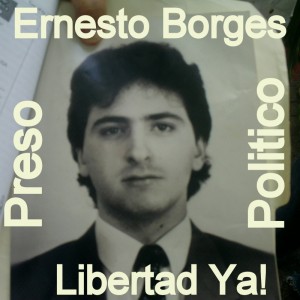

But none of this is more grave for him than the unjust imprisonment of his son, for which–besides everything else he does all the time–Raúl will do everything possible to join those hundreds of other persons who, all over the country, will demand the freedom of prisoners like his son, Ernesto Borges Pérez.

Neither his age nor physical condition will keep Raúl from trying to break through the lines of guards that start to form as of Thursday or Friday, and later, if he succeeds, he will not be ashamed to be thrown, like so many others, in the back of a truck or a bus headed for jail cells or to a remote and isolated spot where he would be put out to find his own way home, nor to be shackled and beaten, with no care as to whether the chosen target for the punch is his scarred chest–as it was four Sundays ago.

But a father’s love is not to be disdained next to that of a mother, for all the insistence by some that anyone can be a father, but a mother can only be one. Raúl is the refutation of this erroneous suggestion. And in the love of a father determined to do whatever it takes to gain the freedom of a son who is considered to be unjustly imprisoned, those who try to subdue civilian forces through violence will find an irresistible force, no matter how aggravated the confrontation may be.

None other than a Cuban State Security agent admitted as much to César, Raúl’s other son, when he warned him that he could not be responsible for the life of César’s stubborn father. “But,” the agent acknowledged, “were I in his place, I would do the same.”

Translator: Alicia Barraqué Ellison

21 June 2015