In Cuba there are no institutions that guarantee the rights of the most vulnerable. Prostitution is not even mentioned as a problem by the Government.

In Cuba there are no institutions that guarantee the rights of the most vulnerable. Prostitution is not even mentioned as a problem by the Government.

It is said that prostitution is the oldest occupation in the world. There aren’t any cultures whose histories have not recorded the practice of sexual services in exchange for money or something of value. Other forms of prostitution are fashioned in exchange for favors or privileges.

Prostitution’s time-worn persistence throughout the ages offers an almost infinite variety of forms, circumstances and considerations, sociological and psychological as well as historical, economic, gender-associated and even political. The darker margins of the phenomenon today refer to the trafficking of women through international networks specializing in human trafficking for sexual means –- victims of which are illegal immigrants and young people in impoverished areas — slavery and, specifically, the trafficking and sexual exploitation of children.

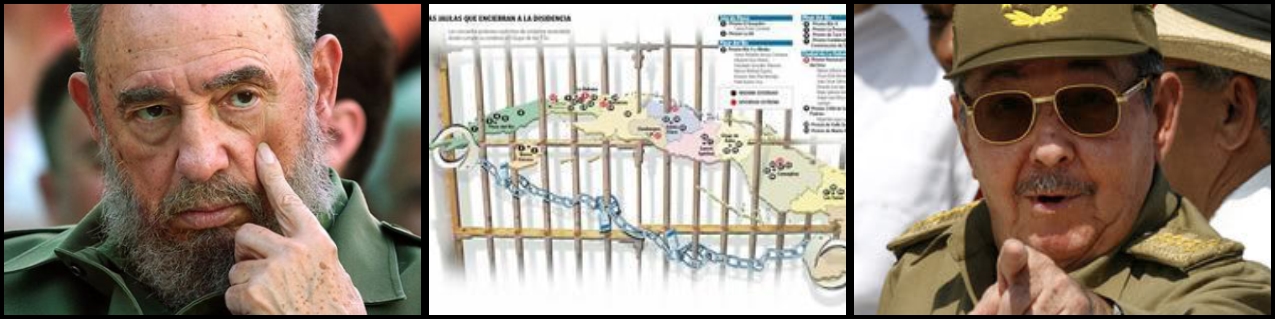

Prostitution in ‘Revolutionary’ Cuba’

Recently, the Miami newspaper El Nuevo Herald published an article about the so-called prostitution’s “hustling” (George Porta, El Jineterismo es una Forma de Genocidio [Prostitution is a Form of Genocide] ), which brings into discussion the issue of prostitution in a country that was considered a territory free of the sex trade in the decades following 1959.

“Hustling” is the expression in the marginal vocabulary that defined the prostitution that started to proliferate more strongly in Cuba since the decade of the 90’s of the last century, fueled by the economic crisis after the collapse of the former USSR and the socialist camp, and the increase of tourism as an alternative, developed by the government to generate foreign exchange income. Thus, it is all the more controversial because Cuban prostitutes in the last 20 years don’t stem from — as often happens in other underdeveloped nations — social sectors hit by illiteracy, ignorance and other similar afflictions, but are members of generations formed and indoctrinated in supposedly superior moral principles of “the new man” and many of them hold significant educational levels.

The image of the poor naïve country girl, deceived by some wily suitor who “disgraced” her and ended up exploiting her in some brothel in a provincial city center or at the capital was left back in pre-1959 history. Today’s prostitute is usually a young woman who has completed at least the ninth grade and who consciously uses her sexual attributes to achieve, in a brief time, the material benefits that she knows she cannot achieve from a salary or from the practice of a technological or professional university career.

The “hustling” does not represent a homogeneous caste either. This is a well-differentiated phenomenon in layers or strata, by category, age, physical attributes, qualifications, aspirations, relationships and other factors, of the young woman in question. Thus, there are different types, from the cheap street “jineteritas”**, that satisfy quick sex in a car or in a hallway or small room in a hovel to the spectacular and expensive prostitutes at gyms and spas, beautiful and refined, providing a more “personalized” service, many of whom dream of an advantageous marriage to a dazzled foreign tourist or to some executive at a mixed-capital firm, or to accumulate sufficient funds to emigrate by themselves.

Between both extremes is a world of prostitutes of the most diverse conditions and goals, many whose minimal objective is to survive day-to-day, with no plans or ambitions, dependent on a reality without expectations for a future.

However, the causes of prostitution in Cuba, though they relate to the ongoing economic crisis and the rise of international tourism, are deeply rooted in the deterioration of other values not necessarily linked to the issue of gender inequality, sexism or oppression of women. The phenomenon is much more complex and has deep surges, a legacy of the vulgar egalitarianism that prevailed in the years of subsidized socialism.

Sometime after, there was an inversion of values in Cuba in the social appreciation of the prostitute. Many of these women who used to sell their sexual services to foreigners in the 90’s – previously a reason for disdain and social stigma – turned into a sort of popular heroines, when they became family providers and sometimes even benefactors of their distressed neighbors. In particular, the “class” prostitutes who often provided medicine, hygiene products or food to the most destitute, significantly changed the perception of the profession: to prostitute oneself was not only more lucrative, but could be considered as a source of solidarity and prestige. By the way, by then, we Cubans were not that “equal”.

The same transformation did not take place with the lower-class prostitute. Segregationist prejudice gained momentum starting in those years, stemming from differentiations in purchasing power which spontaneously settled among prostitutes as well. Before Castro, the poorest prostitutes were popularly known as “coffee with milk”. Today’s are “sugar water.”

Having said that, could a jinetera always be defined as a victim of gender and of poverty? Does jineterismo, as in prostitution in Cuba, adjust itself to the definition of “genocide” that the article in El Nuevo Herald proclaims? Personally, I prefer to turn away from the hype. It is a fact that prostitution as a social phenomenon favors the proliferation of related crimes: pimping, human trafficking, gender exploitation, drug trafficking, etc. It is also axiomatic that the material shortages, coupled with the moral crisis, stimulate the spread of prostitution in Cuba.

However, beyond social “tolerance”, experience shows that there are survival options not associated with prostitution that were adopted by most of the women in Cuba, even in the worst moments of the crisis, and that a high percentage of prostitutes voluntarily elected that profession as the most expeditious, for profit and not just for “reasons of survival.” Thus, a large number of prostitutes do not feel the need to be “liberated” from an activity that offers them what, in their perception, is defined as “freedom”: purchasing power above the Cuban medium.

It isn’t about denying the existence of prostitution either, or the importance of anticipating its consequences, but about more accurately interpreting the facts. Assuming the inevitable, everything points to the certainty that prostitution has returned to stay: there is no tourist destination that doesn’t attract this type of profession. So what will matter is how we’ll deal with it.

In principle, any adult of sound mind is the owner of her own body and of her acts, as long as she does not undermine the rights of others, so being a prostitute or not would be – in the first place – a matter of choice, depending on whether the law determines if it constitutes a crime or not, and whether they pursue related criminal activities. Another issue is when a person is forced into prostitution, in which case it is a flagrant violation of her rights as a human being.

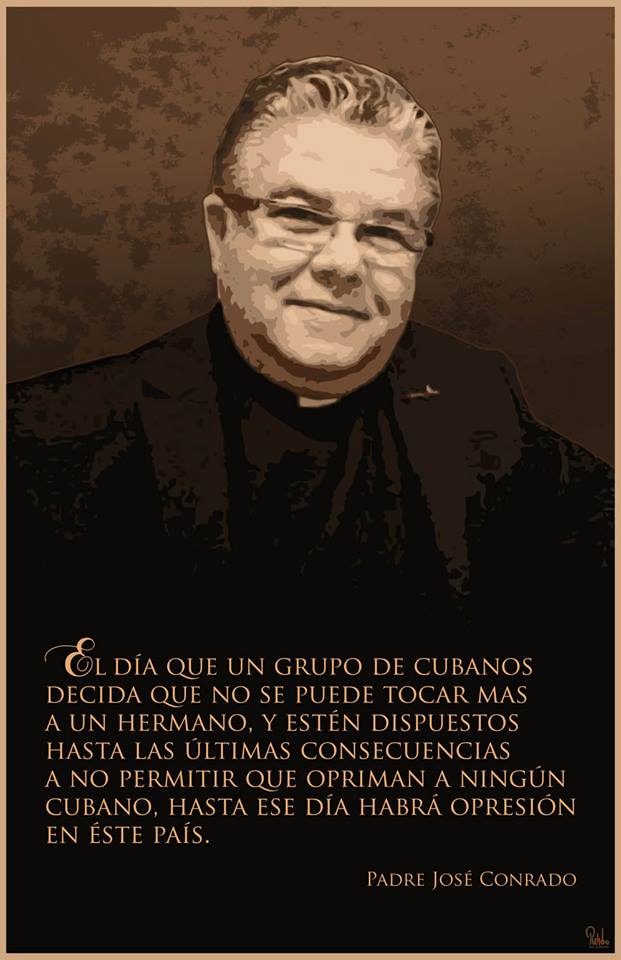

It is reprehensible that there are no institutions in Cuba capable of guaranteeing the rights of vulnerable social sectors, that prostitutes are unprotected, that the prostitution of minors is not prosecuted and condemned severely, that the roots of evil are not confronted, and that laws are almost always limited to punishment (the so-called “re-education”) of the prostitute, the weakest link in the chain. Cuban prostitutes, especially the “street” ones, are more likely to be victims of violence, whether by a pimp or by police extortion. On not few occasions the pimp and the police are the same person.

The issue of prostitution is hot, and it’s even part of the political agenda in many developed countries. Some current proposals focus on the regulation of prostitution, previously legalized, though a strong trend has also developed in favor of criminalizing the purchase of sexual services and not their sale.

In Cuba, unfortunately, we are very far away from instituting an effective strategy on the subject. It is known that the first step is to recognize the existence of the phenomenon, submit it for public debate and study its scope and social consequences, which requires the political will of the government: all of it a chimera

In any case, this could well be an important point on the agenda of many independent Cuban organizations interested in problems with a civilian edge. So far, there are no thematic programs on the issue in the emerging civil society. Starting and sustaining the debate will be the initial stimulus that will unleash the proposals.

*Jinetera: female jockey or horse rider, used graphically in the context of hustling.

**Jineterita: diminutive form sometimes used to describe an unimportant, insubstantial, or young prostitute.

Translated by Norma Whiting

21 August 2013