This post is from Pedazos de la Isla which can be read in English here. The blog is the work of Raul Garcia, Jr. who translates innumerable blog posts and supports and encourages the bloggers via email and telephone.

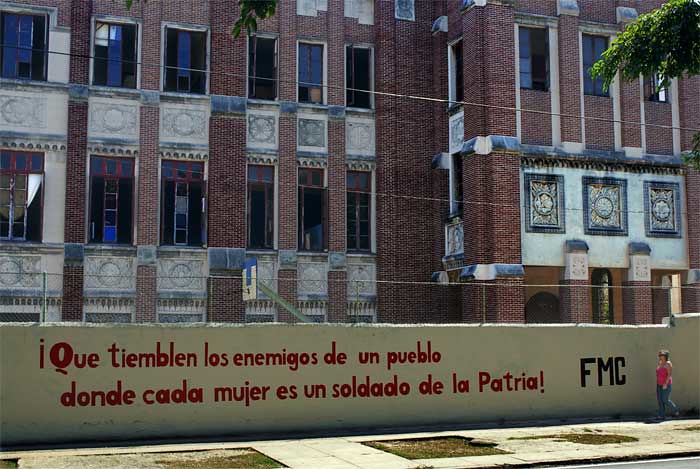

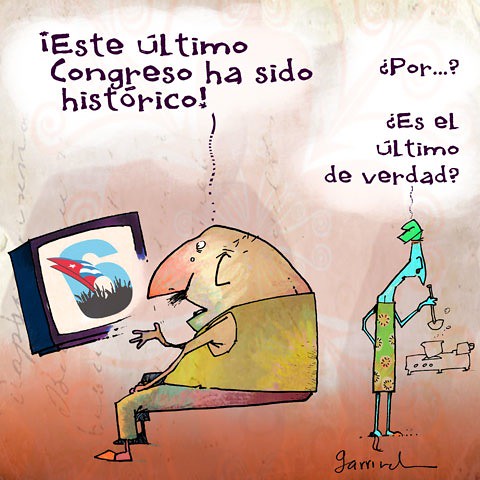

Following the celebration of the ignominious 6th Communist Party Congress in Cuba this past Saturday April 16th, various international media outlets have baptized the event as a “step towards reform and changes”. The regime of Havana, content with such a reception, continues trying to promote its image of benevolent “reformist” through their propaganda tactics. Interesting enough, many of those news reports done by international reporters do not make much mention about the massive military parade which was held just a few hours before the Congress. Ironically, they rapidly point out the promises and the supposed achievements of the revolution, but ignore to also point out that the Cuban government continues promoting (and using) violence within Cuban society.

The reality within the island continues to be the same, if not worse, as always. The political police, responding to direct orders from those who reside in power, continue to mistreat, beat, incarcerate, and threaten peaceful dissidents.

Since the Cuban state does not allow dissenting or opposing voices to be heard through the national media, I decided to dedicated this space to some voices which represent that dignified resistance movement within Cuba, as well as civil society. We have already been able to read the commentaries made by the Cuban press and by the international press, but now I invite you all to hear some reports straight from the island. Listen to their opinions about the massive military march and the 6th Communist Party Congress. I had the immense luck to chat with each one of these brave Cubans and closely listen to their reactions. I refer to these voices as “free voices” because, despite the fact that they are living under a totalitarian state which prohibits democracy and free expression, they are brave individuals who have chosen to live like free human beings, choosing to face any risks or repressions for saying and doing what they think, as opposed to remaining quiet and letting themselves be swallowed by apathy and desperation.

Laritza Diversent

” The military march, which was made up of all those military machines which, I must confess, I do not even know what they are called, was simply a message on behalf of the Cuban government which said ‘look at the arsenal of weapons we have’. In other words, it was a way of saying that they are prepared for any kind of attempt against them. Many people inside of Cuba, mainly the men who have gone through military service, know that all those equipments and tanks are Russian technologies that cannot be compared to modern military technology currently in use throughout the world. All the equipments displayed in the march are practically obsolete. What people were really complaining about were extensive expenses attached to the display, meanwhile the country is going through a difficult economic time, when each day the prices of basic goods goes up, mainly the price of food.

The military march, which was made up of all those military machines which, I must confess, I do not even know what they are called, was simply a message on behalf of the Cuban government which said ‘look at the arsenal of weapons we have’. In other words, it was a way of saying that they are prepared for any kind of attempt against them. Many people inside of Cuba, mainly the men who have gone through military service, know that all those equipments and tanks are Russian technologies that cannot be compared to modern military technology currently in use throughout the world. All the equipments displayed in the march are practically obsolete. What people were really complaining about were extensive expenses attached to the display, meanwhile the country is going through a difficult economic time, when each day the prices of basic goods goes up, mainly the price of food.

From my point of view, the Congress was totally insignificant, because they say one thing there but what they do in reality is something else. One of the characteristics of Cuban politics is that it is very fickle. At one moment, they decide one thing and next thing you know they change their decision completely. Taking these processes into account, they celebrate their Congress, they take their measures, and they reach agreements upon themselves. There is no restructuring of the Party and there is no democratic restructuring either. But none of this has any importance for the citizens of Cuba. It has no importance in comparison to the importance it has outside of Cuba. And this is precisely because very few Cubans are interested in politics, or simply they do not understand it. And they feel this way because of the “back and forth” of the government, while one day it says one thing, tomorrow it’ll say another, and so on. Because of this insecurity, we do not pay any attention to this Congress.

All those civilians present in the march do not go voluntarily. At stake are their salaries, compromised primarily of foreign currency, their jobs, etc. Most of the time, the government does not say that it is mandatory to assist such events but those who were born here in Cuba know very well that what they say is ‘those who wish to go, may go’, but they also know that there exist political guarantees which follow you wherever you go (primarily in work or school), and that there are consequences waiting in store. Bonuses are given to “the best”, not to those who do not carry out the chores assigned to them by the revolution”.

Luis Felipe Rojas

“The military march was a pure display of muscles; a demonstration of force in a country where the sale of arms is prohibited and where the possession of any sort of weapon is highly penalized. This country has not received a single attack since 1961, and even then, it was not carried out by foreign forces but instead by a group of non-conformed Cubans. The weapons we saw displayed in the march were obsolete in comparison to the modern weapons displayed elsewhere in the world. The purpose of the march was not to prevent any invasion, but to instead to prevent any sort of uprising against the commandments of the Cuban revolution.

“The military march was a pure display of muscles; a demonstration of force in a country where the sale of arms is prohibited and where the possession of any sort of weapon is highly penalized. This country has not received a single attack since 1961, and even then, it was not carried out by foreign forces but instead by a group of non-conformed Cubans. The weapons we saw displayed in the march were obsolete in comparison to the modern weapons displayed elsewhere in the world. The purpose of the march was not to prevent any invasion, but to instead to prevent any sort of uprising against the commandments of the Cuban revolution.

The Communist Party Congress, presided over by General Raul Castro, leaves the Cuban people with more doubts. I also must point out that none of the previous agreements of the 5 other Communist Congresses have ever been fulfilled. More than 40 years have passed since the first Party Conference and they have not fulfilled a single one of the accords. So then, the question is, what are the party members really doing? The low quality and degree of inefficiency of the Communist party is really tiresome.

No concrete measures which could improve the life of the people have been established. And I say this in regards to those who were actually hopeful about this Congress. I was one of those who wasn’t expecting any changes”.

Marta Diaz Rondon

“The military march held in Havana was only done with the purpose of intimidating the people, so that they would not protest. It was a way for the government to show that they have special troops ready to confront any person who would decide to take to the streets at any moment. That’s why the march was strategically held before the Congress. But despite that, the people are still protesting because it has been 52 years of suffering for us Cubans. We have been the ones that have had to live through all of this.

Those who are most corrupt are those who govern the country, starting with the Castro brothers and all the way down to the Central Committee, including all those who govern in the provincial levels.

This past Tuesday, April 12th, I met with a group of rural opposition members in Los Pinos, Banes. There we started conversations and debates regarding the famous 6th Communist Party Conference. The Congress, of course, is a facade because it is only the rulers who are allowed to take part. No other Cuban is allowed. Every person there is chosen by the government.

During Thursday of last week they were organizing a mob act against me in Banes. At that moment I wasn’t in Banes, though, as I had left early that morning to Holguin to meet with the activists. Ever since Wednesday, Banes has been under tight surveillance of the political police. The entrance of Reina Luisa Tamayo’s home is completely surrounded by police and they are not allowing anyone to go in. I believe that the government is fearful that the people will take to the streets, seeing as Cubans are suffering more each passing day.

I think the Communist Party Congress is very unfavorable for us Cubans, the everyday Cubans. And we are already protesting on the streets”.

Caridad Caballero Batista

“First of all, this government has always used things like this military march to its advantage. They’ve always had their people threatened and harassed. Those are the characteristics of the rulers of our country. It’s a way of symbolically saying ‘this is what we have for you’. Raul Castro said he was going to continue in power and also spoke of some other measures, but none of which are good news for Cubans. There is a total state of abandonment towards the people. Any benefits are reserved for those in power, leaving the rest of the country with no options.

During all of this, Ulisses Ramon Llanes, a prisoner, died in the Granma provincial prison because of scarce, or no, medical attention. The countries’ rulers have never paid attention to any of this. The jails are full of men who are practically innocent and they are left to die because of scarce medical assistance, physical abuses, etc.

The Congress was simply a list of restrictions for the country.

Castro also mentioned that the government could not keep the “people” from defending their streets. But those who carry out mob acts are not spontaneous people; it is their people who oppress the opposition.

Every passing day we continue to be dissatisfied and we are constantly expecting the worse on the government’s behalf, because they will never facilitate anything for us”.

Pedro Arguelles Moran

The military march was an awful waste which consisted of far too much wasteful economic spending, which instead could have been invested in Cuban society- in the production of food, goods, and services. But it was definitely not worth it to spend that extraordinary amount on something that is not important, something that is violent and against humanity instead of investing on medicine or education. I consider it to have been unnecessary, absurd, and ironic, especially in a time where we are demanding peace, solidarity, and national reconciliation. To me, it’s simply absurd. This has all taken place in a country where the economy does not exist and that is in a total crisis.

The march is just a form of intimidating the population because the government is aware of the fact that the people are paying attention to what is happening in Northern Africa- in Egypt, Libya, etc. They are sending out a warning to the citizens that they have military powers.

As for the Congress, it was just another form of demagoguery. It’s another act of populism, and none of the problems which Cuba faces will be solved through that Congress. It’s simply the continuation of the same. And in addition, they also justified the despicable mob attacks against dissidents.

The people know that it is all a lie. They do not believe in the Congress, because they have lived through more than 50 years of lies. The Communist Party Congress was a psychological tactic to give off the illusion of openings and changes.

More to come…

The military march, which was made up of all those military machines which, I must confess, I do not even know what they are called, was simply a message on behalf of the Cuban government which said ‘look at the arsenal of weapons we have’. In other words, it was a way of saying that they are prepared for any kind of attempt against them. Many people inside of Cuba, mainly the men who have gone through military service, know that all those equipments and tanks are Russian technologies that cannot be compared to modern military technology currently in use throughout the world. All the equipments displayed in the march are practically obsolete. What people were really complaining about were extensive expenses attached to the display, meanwhile the country is going through a difficult economic time, when each day the prices of basic goods goes up, mainly the price of food.

The military march, which was made up of all those military machines which, I must confess, I do not even know what they are called, was simply a message on behalf of the Cuban government which said ‘look at the arsenal of weapons we have’. In other words, it was a way of saying that they are prepared for any kind of attempt against them. Many people inside of Cuba, mainly the men who have gone through military service, know that all those equipments and tanks are Russian technologies that cannot be compared to modern military technology currently in use throughout the world. All the equipments displayed in the march are practically obsolete. What people were really complaining about were extensive expenses attached to the display, meanwhile the country is going through a difficult economic time, when each day the prices of basic goods goes up, mainly the price of food. “The military march was a pure display of muscles; a demonstration of force in a country where the sale of arms is prohibited and where the possession of any sort of weapon is highly penalized. This country has not received a single attack since 1961, and even then, it was not carried out by foreign forces but instead by a group of non-conformed Cubans. The weapons we saw displayed in the march were obsolete in comparison to the modern weapons displayed elsewhere in the world. The purpose of the march was not to prevent any invasion, but to instead to prevent any sort of uprising against the commandments of the Cuban revolution.

“The military march was a pure display of muscles; a demonstration of force in a country where the sale of arms is prohibited and where the possession of any sort of weapon is highly penalized. This country has not received a single attack since 1961, and even then, it was not carried out by foreign forces but instead by a group of non-conformed Cubans. The weapons we saw displayed in the march were obsolete in comparison to the modern weapons displayed elsewhere in the world. The purpose of the march was not to prevent any invasion, but to instead to prevent any sort of uprising against the commandments of the Cuban revolution.

Migdalia and Ramon can’t watch the afternoon sopa opera since the State inspectors confiscated the antenna in the middle of February.

Migdalia and Ramon can’t watch the afternoon sopa opera since the State inspectors confiscated the antenna in the middle of February.