I suspect that somewhere from the island firmament, the writer José Lezama Lima (Havana, 1910-1976) is smiling at his supporters, or winking at the editor who introduced the latest edition of his Collected Works. Our literary rhino should be happy with so many celebrations. “Seeing is believing”, he would say at one of the gatherings for his Centennial, nearly four decades after his death, which was preceded by ostracism and suspicion because of his “detachment from reality.”

I suspect that somewhere from the island firmament, the writer José Lezama Lima (Havana, 1910-1976) is smiling at his supporters, or winking at the editor who introduced the latest edition of his Collected Works. Our literary rhino should be happy with so many celebrations. “Seeing is believing”, he would say at one of the gatherings for his Centennial, nearly four decades after his death, which was preceded by ostracism and suspicion because of his “detachment from reality.”

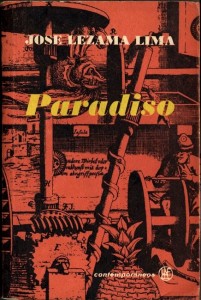

The sanctification of the author of Death of Narcissus (1937) and the controversial Paradiso (1966), represents the triumph over the censorship imposed at the time of revolutionary change, more suited to the aesthetics of violence and socialist realism. Censorship is still standing, but dead authors do not frighten the curators of the culture, who reprinted the poems, essays and novels of Lezama Lima, in addition to his letters, interviews and lost texts reborn in anthologies, in seminars, conferences , documentaries and even feature films.

Those who think that behind the exaltation of Lezama Lima there are ulterior motives, are right — particularly in this year of his centennial, a year marked by crisis and despair generated by the same dictatorship that buried in silence so many writers and artists. Lezama himself, decades ago, recognizing the adverse historical circumstances, said that “a country frustrated in political essentials can achieve virtues and expressions by other more royal hunting grounds.”

For him, art and literature were more enduring royal preserves; centers of gravity in his life and his work, dedicated to jumping beyond the immediate and transcending the political roughness and daily gossip. Thus, his creative fertility did not take the path of social protest, but the inclusive tradition that rescues the Cuban essence and merges with other legacies through a long artistic language.

The great Lezama Lima’s unique poetic corpus and controversial theory of the image should be like an engine of history. For him, “poetry is like the dream of a doctrine.” His enormous talent and erudition confirmed the riddle in poems of rupture such as Death of Narcissus (1937), Enemy rumor (1941), Concealed Adventures (1945), Persistance (1949) and Giver (1960), complemented by essays that offer new critical perspective and the novel Paradiso, published by the UNEAC in 1966 and reissued by Letras Cubanas in 1989, with an indispensable foreword by Cintio Vitier.

The great Lezama Lima’s unique poetic corpus and controversial theory of the image should be like an engine of history. For him, “poetry is like the dream of a doctrine.” His enormous talent and erudition confirmed the riddle in poems of rupture such as Death of Narcissus (1937), Enemy rumor (1941), Concealed Adventures (1945), Persistance (1949) and Giver (1960), complemented by essays that offer new critical perspective and the novel Paradiso, published by the UNEAC in 1966 and reissued by Letras Cubanas in 1989, with an indispensable foreword by Cintio Vitier.

The Death of Narcissus and Paradiso represent his ticket to literary immortality. The imaginative display, linguistic input and the way he retells the myths of the past and beings them closer to the island horizon, caused critics to see in Lezama Lima our Luis de Góngora.

Paradiso, described as secretive and scandalous, recreates the family and personal guts of Lezama Lima himself, who submitted to the reader the geometry of words, but he gives away his arsenal of parables, cultural associations, metaphors, dreams and unexpected visions. We should search the work and recreate ourselvs in it as a cathedral of history, friendship and culture far from the melodramatic thrillers and detective novels.

It is also possible to read the essays, Analecta (1953), The American expression (1957), Treaties in Havana (1958), The bewitched (1970) and the compilation Image and Possibility of 1981. In 2010 studies on cultural dissemination undertaken by Lezama Lima resurfaced in magazines that identified his generation, consisting of figures that, with him, enriched the spiritual heritage of Cuba. From Verbum (1937) to Origens (1944-1956), past Silver Spur (1939-1941), Poet, Clavileño, Nadie Parecía and Fray Junipero (1943).

Origins, with 40 issues in a decade, was compared with the Revista de Occidente (Spain), with the River Platte South and the Mexican Contemporáneos e Hijo Prodigo. In Origins, Lezama and his colleagues structured the first literary movement that made poetry its essential form of knowledge, aesthetic enjoyment and understanding of the world. Here are the voices of our poetic transcendentalism, who include, in addition to Lezama, Gastón Baquero, Eliseo Diego, Cintio Vitier and Fina García Marruz.

A hundred years after his birth Lezama Lima is still more talked about than read, but he is also reborn as a paradigm of the creator outside the socio-political reality of the country, where the calm waters and the daily hardship stimulate the search for other estates of greater royalty.

December 28 2010