The last conga just went by. The street is half-lit, dirty, with remnants of viewing platforms and dismantled stalls, all now barely but a memory. The 2012 carnival has come to an end.

The last conga just went by. The street is half-lit, dirty, with remnants of viewing platforms and dismantled stalls, all now barely but a memory. The 2012 carnival has come to an end.

Nothing about the city’s atmosphere gives any indication of what has just transpired. Only those living close to Havana’s Malecón have been witness to these impoverished evening festivities, with their large amounts of beer and rum, empty plates of rice with beans and slices of pork or chicken, and most notably widespread promiscuity. All this in an ever more restricted space of not much more than a few blocks.

How different from the carnivals of Havana’s distant past, which rivaled the most important in the world—Carnaval in Río de Janeiro, Mardi Gras in New Orleans and the very glamorous Carnival of Venice, to name a few—all of which took place in February and March before Lent.

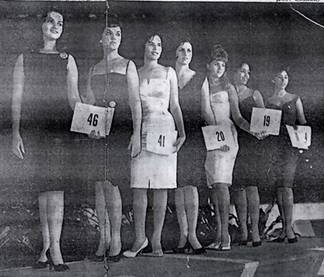

In the case of ours there was a carnival atmosphere for months before the festivity itself. There were the competitions to choose the best poster, which would later provide that year’s theme, the sewing, the almost secret preparations of the floats that would represent the different groups sponsoring them, each with its own queen, and the rehearsals of various neighborhood carnival organizations. The entire city prepared and decorated for the much anticipated event. The selection of the Queen and her Maids of Honor—renamed Estrella and Luceros, or Star and Shining Stars, after 1959—was the climax of these preparations. Large photo portraits of them adorned the display windows of the main retail stores.

As a child I very much enjoyed these celebrations, always spent with my family and usually in a box near the Capitolio. Once the parade had ended and the last float and its crew had turned the corner at the Fountain of the Indian to return to the starting point near the Hotel Riviera, we children ran into the street to gather up the streamers and make big balls out of them, all under the watchful eyes of our parents. In general, though, it was all very safe. No one got drunk.

After the 1960s these celebrations gradually lost their splendor. There were no more sponsorships. The state had taken over everything. I remember one day at my workplace the union representative came by to announce that Estrella would be chosen at a general meeting that afternoon to represent us and the sugar cane harvesters at carnival. They told all of the girls who worked there to fix ourselves up a bit before going to the meeting. To my astonishment I was chosen to represent the company. Afterwards I had to compete with ladies from the ministry’s other businesses, later with those from the trade unions, and finally at the sports stadium, where in the end I won. It all happened very quickly, as though it were a dream.

I can assure you, without a shadow of a doubt, that this was the quite possibly the last year in which there were luxurious floats. The theme of ours was the bottom of the sea. Now, looking back on it after all these years, it strikes me that it was like a portent of what awaited us—to touch bottom, as we are doing now.

August 29 2012