Given the chance, they become informants for the police or the special services. Many ordinary Cubans view them as true degenerates; others simply consider them to be opportunists.

One thing is clear. If anyone has been able to take full advantage of the system designed by the Castro brothers, it is the administrative “cuadros.” Take the case of two such “compañeros” who work for the bulging governmental bureaucracy.

Let’s call them Roberto and Fermín. They do not know each other, but they behave like twin souls. They both carry black suitcases, each containing a stack of papers with official letterheads. By the time they head for home, these are packed with goods and cash obtained over the course of a normal work day.

Within the “cuadro” caste system there is a low, medium and high class. The closer one is to the pinnacle of power, the greater the cash and benefits one receives. Robert and Fermín belong to the middle class, the one that does not call too much attention to itself.

Robert is the manager of a nightclub. When summer comes, he begins his “dance for the millions.” He is a member of the Communist party and leader of a squad that, in the event of disturbances, heads to the barricades to beat up dissidents. Like most Cuban men he has spent time in the military, and is ready to do his part in a hypothetical war against the American marines.

One day a week he meets with his party cell. In his suitcase Roberto carries three bottles of premium rum. After a tedious meeting, he and his pals drink the rum. A little while later he suggests they kick back a little. From his mobile phone he calls a quartet of statuesque, bisexual girls, and in a house near the beach they engage in a boisterous orgy.

Roberto refers to such squandering of financial resources as “the cost of doing business.” It is a way of keeping high-level political bosses on his side. From time to time he “soaks” them with money, letting them in for free to his discotheque, where their tabs are on the house.

A clever “cuadro” weaves a web of influential friendships. Among Roberto’s friends are members of the military and state security. The Havana resident knows, however, that, in the event he one day he finds himself behind bars, they will be of little use to him.

But while he still can, Roberto takes full advantage of these friendships to intimidate his bosses and take care of small matters. Having a guy with three-stars is like having a guard dog at your side. It’s a guarantee.

That’s why it matters little that one of his military buddies swings by the nightclub with some regularity to fill his Chinese-made vehicle with two cases of beer, several bottles of whiskey, chorizo sausages from Spain and half a leg of ham.

Roberto recovers these costs by night. It is key for an administrator in the tourism and restaurant industry to have someone who specializes in covering up graft. One’s accountant must be a magician. That’s what makes embezzlement work.

Coming off as a member of the khaki green power structure is essential to maintaining an expensive lifestyle. Roberto owns two cars and each of his sons drives a motorcycle. He has more than one lover and a reasonable amount of cash hidden away in different locations. He never passes up the chance to make some money. If the Ladies in White need to be roughed up, you can count on him.

But his main adversaries now are not these female “mercenaries.” It is President Raúl Castro and his circle, especially the Comptroller General of the Republic, Gladys Bejerano. Her audits are making things difficult for him. Every day he is able to steal less and less.

“Cuadros” like Roberto ask themselves how far the General, who doesn’t seem to be playing games, is determined to go. Roberto feels screwed by a form of persecution being carried out against the middle and lower classes, the ones who support the “system” — a word synonymous with government, revolution and socialism.

Meanwhile, as long as they don’t get caught, they have immunity and can carry around suitcases full of cash. The crime mobs within the restaurant and tourism industry are still mapping out their strategies. They are still stealing. They have always done it, and they see no reason why they should stop now.

Fermín is another one of the system’s “cuadros.” He works in a department at the Union of Young Communists. He graduated from a party-run school where he memorized numerous treatises by Karl Marx and stretches of speeches by Fidel Castro.

This young “cuadro” was so indoctrinated that, when he spoke, he sounded like a Castro clone giving a harangue. He has forgotten neither the Marxist textbooks nor the speeches. He now employs them discreetly. As the need arises.

One morning, while imploring factory workers to increase production, Fermín raises his voice and allows himself to be swept away by revolutionary fervor and heated rhetoric. After the requisite applause he heads off to a poor neighborhood, changing his oratorical style and adapting it to the marginalized audience.

That afternoon Fermín meets with a friend from childhood, who moves through the underworld like a fish through water. This is the person who pays him in convertible pesos for invitations to discotheques and nightclubs that Fermín has stolen.

It is a “legal” way to obtain hard currency. With this money and the diversion of shipments of chicken and cheese intended for his organization’s “recreational activities,” Fermín has opened a private cafe using his friend as a front man.

The profits are high. He gets most of his supplies for free or at very low price. Fermín has already renovated his house, and is making plans to set up a cozy love nest at a girlfriend’s place.

Unlike Roberto, Fermín is not worried about Raúl Castro’s offensive against corruption and out-of-control bureaucracy. Time is on his side. He is 29 years old and there is a promising political future ahead.

His goal is to climb the winding staircase of the status quo. When God calls the Castros and the other elderly leaders home, he wants to be well-positioned. Power likes nothing better than money.

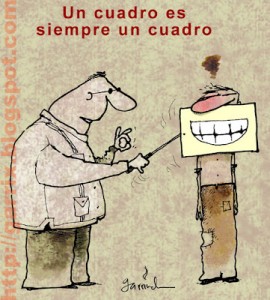

*Translator’s note: The cartoon makes use of a pun. The cartoonist and author are referencing three separate meanings for the Spanish wordcuadro, which can mean either a square, a painting, or in Cuba the type of person discussed in this blog post.

August 12 2012