As a result of the next baseball season, the State press and fans have unleashed a debate, looking to raise the level of ball played on the island. There were more than 170 proposals to design a new competitive structure.

As a result of the next baseball season, the State press and fans have unleashed a debate, looking to raise the level of ball played on the island. There were more than 170 proposals to design a new competitive structure.

In a meeting with the national press, the Cuban Federation let it be known how the next tournament will be structured. The league will open on 25 November in José Ramón Cepero Stadium with a matchup between the present champions, Ciego de Ávila and the runner-up Industriales. Sixteen sides will participate, one for each province plus the special municipality Isla de la Juventud. The Metropolitanos team is eliminated, with their 38 years of history in the local classic.

The schedule will consist of two stages. In the first, 45 games will be played in a round-robin to find the best 8 teams. The sides that go on to the next round will be able to draft up to five players from the teams that didn’t qualify. This phase will be of 42 games. In two playoffs of the best of seven, the four winners will play for the national championship.

It might be that the old structure of 4 divisions and two zones, East and West, was already inadequate. In the last twelve years, the level of baseball has declined a lot. The problem isn’t about a team. Many remain. The keys to elevating the quality of play happens to have a new structure. But the worst evil isn’t that of structure.

The design of the Cuban baseball system used to work. It was a pyramid of skills that included little league, Pony leagues, Youths, and provincial series, culminating in the national classic.

Sports schools perfected and trained the best talent nominated by coaches. Afterwards the harvest was brought in. Until 2006, Cuba won most of the International Baseball Federation’s organized tournaments in every one of its categories.

Now we barely win championships. And that worries fans and specialists. In world tournaments of Pony or Youth Leagues, it’s understandable. The best talents of Asia and the United States take part. But at the highest level, except for the Classics, those authentic discards with skills of little caliber enroll for their respective countries.

In my opinion, there’s a glaring error on the Federation’s part. And it is to implement changes thinking only about the national team. The series on the island cannot be a satellite that circulates outside that orbit. It must be independent. When the season has more quality, the higher the level that will be achieved by the Cuban team.

What we’re talking about is how to really raise the level of ball played. The options are many. But all will happen by opening the gate and allowing the best ball players to compete in foreign leagues. The ideal would be to arrive at an agreement with the Major Leagues such that Cuban players can sign contracts without having to abandon their country.

But current laws complicate the proceedings. As such, other destinations would have to be chosen. Japan and South Korea, due to the high level of their leagues, would be the best.

Another step that can’t be overlooked is pay and material conditions for the players. It’s a failed subject. Local idols who were sometimes Olympic champions got 300 convertible pesos — about 340 dollars — a ridiculous amount for a first-rank sportsman; although in the difficult economic conditions this country lives in, it’s a ’fortune’.

An effort should be made so that players in the national series can earn salaries greater than 3000 pesos ($130). The solution might be to raise the price of tickets to stadiums from one peso to five, with part of the proceeds distributed between players. Not equally. The regulars would earn more. The extra class, much more. Local and foreign companies based in Cuba, with its productions, could be sponsors.

It should not be possible that a national champion, as in the case of the Industriales in 2010, should motivate its players through gifts of cement shingles to repair the roofs of their houses, or microwave ovens, defective on top of it.

The majority of Cuban ball players live in precarious conditions. Only a handful of stars live in good houses or have cars. When they look at their colleagues who’ve left the country, they know that playing in a mediocre league they will earn enough to help their own and live decently.

Then they decide to leave. It’s true that few reach the Big Leagues. But they try to integrate themselves in whatever Caribbean, European, or Asian league. Another big problem is the little attention paid by the Federation to the farm systems that feed the national series.

Provincial tournaments of the big leagues are very short. Many games are suspended for lack of balls, bats, and transportation. Ball players are playing out of uniform and don’t even have a snack. You have to love baseball a lot to play in 92 (Fahrenheit) degree heat under these conditions. To this, add that the official press barely covers them — they’re almost clandestine.

In the lower categories, the evil is worse. The fields are true potato fields. The quality of the balls and equipment is terrible. In the stands we’ll find parents, loaded down with lunches and snacks for their kids. When a boy decides to play baseball, his parents have to buy his equipment in hard currency. Cash must also be paid for the making of uniforms.

On a radio sports show called Sports Tribune, on the capital’s COCO station, every night official honest journalists such as Yasser Porto, Daniel Demala or Ivan Alonso go at it bare-knuckled, attacking the evils that afflict Cuban baseball. And they offer solutions.

It’s obvious that their claims have fallen on deaf ears. The COCO journalists weren’t invited to the last meeting where the announcement was made about the structure of the next season.

The Federation is walking a tightrope. It doesn’t wish, want or cannot, address the theme with all of its artists. The solution offered is pure makeup. Cuban baseball’s difficulties won’t be resolved in this manner, nor will the ceiling of competence be raised, because it’s not only a problem of structure. There are many others.

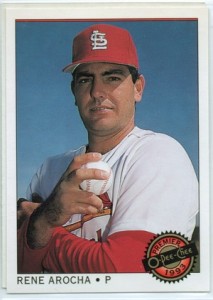

Photo: Taken from The Cuban History. René Arocha, first ball player to desert, 18 July 1991. Since then, more than 150 baseball players have left Cuba and with major or minor success have managed to compete (or still compete) in professional leagues in the United States, Canada, Mexico and Caribbean countries, Europe and Asia, such as Rey Ordóñez, Liván Hernández, José Ariel Contreras, Rolando Arrojo, Orlando “El Duque” Hernández, Kendry Morales, Aroldis Chapman, Osvaldo Fernández, Ariel Prieto, Alex Sánchez, Vladimir Núñez, Danny Báez, Michael Tejera, Yuniesky Betancourt and Yoenis Céspedes, among others.

Translated by: JT

October 7 2012